First gay man diagnosed HIV+ in London on his extraordinary life and feelings on It’s A Sin

Excl: "I absolutely connected with Colin" says Jonathan Blake, who's been living with HIV for 38 years

Words: Jordan Page; picture: Jonathan Blake, left, and Olly Alexander in It’s A Sin, right (non-IAS pics provided by Blake)

Whether you binged the entire series in one weekend like I did, or had more self-control and patiently waited for each episode to air on Channel 4 every Friday, I think we can all agree on one thing: It’s A Sin is one of the most important pieces of television we’ve seen in a long time.

Like any good drama series, it made us experience a tidal wave of emotions. We laughed at Roscoe’s refreshment escapades, we were angered when Jill’s GP rebuffed her, when Ash was picked on by his colleagues, and when Colin was locked against his will in an empty hospital room. And of course, we cried. Whether it was watching Ritchie’s slow decline or Gloria’s family burn her belongings.

While It’s A Sin beautifully honours the experiences of those affected by the AIDS crisis, the truth is that the HIV we see in the series is a far cry from the reality of HIV in 2021. Effective medical treatment means that a HIV diagnosis is no longer a death sentence. People living with the virus can now enjoy long, healthy lives, and by making levels of the virus in the blood undetectable, effective treatment prevents someone living with HIV from passing it on to others. This is a fact, and more people need to know it.

It’s A Sin has undeniably helped increase public awareness of HIV today, with the series breaking All 4 streaming records and encouraging a record number of people to test for HIV from home during National HIV Testing Week. The latter is especially promising, as increased testing is the HIV Commission’s fundamental recommendation towards achieving the goal of ending new HIV transmission in England by 2030.

For some, namely younger viewers, It’s A Sin is their first exposure to the devastation caused by the HIV crisis. But for a lot of viewers, the series takes them back to their lives in the 1980s and 90s. This is especially true for Jonathan Blake, who was one of the very first people to be diagnosed with HIV in the United Kingdom in 1982, back when the virus was known as ‘HTLV3’.

“It’s a great thing that It’s A Sin has happened. Yes, we’ve had documentaries in the past, but we’ve had nothing like this.”

“HIV became the forgotten epidemic – but suddenly it’s now bang in your face. It’s a difficult watch for me. I was asked to review it recently, and watching it on my laptop was moving. But when I watched it on TV it was simply gut-wrenching. Somehow the move from the small screen to the big screen did something – it was really painful at times.”

Jonathan’s journey has been a long one – this October he will have been living with HIV for 39 years. He came to be diagnosed with the virus in 1982 after he says “every lymph node in my body just erupted, I couldn’t even put my arms by my side because of the pain”. After being recommended by his GP to test for syphilis (which swollen lymph nodes are a common symptom of), Jonathan arrived at the James Pringle clinic at Middlesex hospital.

“They were all over me. They wanted to do a biopsy, so I had to stay there for two days, and in those days if you were gay you were put into a sideward so you wouldn’t ‘infect’ the other patients. It was crazy.”

“They came back and said, “You have a virus called HTLV3, there is absolutely nothing we can give you to help. There will be palliative care when the time comes, and you have about six months to live”, and that was that. They said I could go home. They just let me leave. I was absolutely winded. I went home and I just shut the door.”

After his diagnosis, Jonathan shut himself away from the world around him. “I didn’t speak to anyone, I didn’t tell anyone. It was really difficult.”

“I also came to the realisation that I met my virus the year before while visiting San Fransisco. I went to the bathhouses there, and at the time there was kind of a sense of something in the air. But it wasn’t really talked about – it was only later in the year the news started talking about this strange disease that targets gay men.”

In the UK, there was no available information about HIV, apart from whispers in the community about the virus’ spread in America. Eventually, it all became too difficult for Jonathan.

“In December of that year, I attempted suicide. I’d been speaking to my friends in the States and I had simply heard enough of what was happening to people.”

The voice of Jonathan’s mother was in his head, “she would say, ‘you have to clean up your own mess!’”. Thankfully he didn’t go through with it.

“Then it was a question of, ‘I can’t kill myself so I better get on with it and live’. I wanted to be around people, so I went off to pubs and bars. I would stand in the shadows because I’ve got this killer virus coursing through my veins. I didn’t want to infect anybody, and I’ve never been good with condoms. So it was really difficult.”

“I don’t know whether it was the shame, but I just felt really awful and isolated. I didn’t know how to manage it.”

Jonathan’s self-confessed reentry into society was when he attended a nuclear protest with a group of gay men in 1983. It was there he met his partner Nigel – “we spent the whole day together and I told him about my diagnosis, which didn’t seem to have any impact on him whatsoever.”

Nigel eventually persuaded Jonathan to step out of isolation and move in with him to a squat in Brixton. They’ve been living with each other happily ever since.

“That moment completely changed my life. He was very politically active, so when Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) formed, we joined. The most important thing for me was displacement activity, so I wasn’t forever thinking about the diagnosis, the death sentence I had.”

Jonathan continued to live his life, immersing himself in volunteering for drop-in centres for people living with HIV like The Landmark in Brixton and completing education courses which, thanks to the Greater London Council, cost £1 if you were unemployed: “it was phenomenal!”

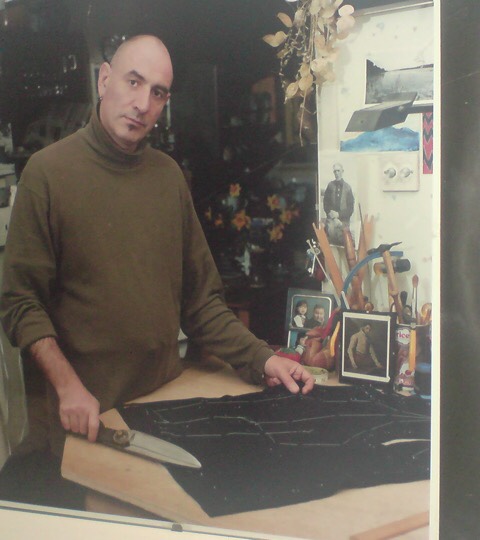

After completing a pattern-making course, Jonathan completed a diploma in tailoring and eventually became an assistant pattern cutter for the English National Opera.

“I remember going to the interview and looking around the walls. They had a noticeboard up and my eye hit this letter from St Mary’s hospital, thanking everyone in the workroom for the support they’d given Peter, the men’s cutter who died of AIDS.”

“That’s when I knew I wanted to work there, because when I get ill they’ll understand.”

Having trained as a tailor and completed work experience at Savile Row, Jonathan related to Colin’s character in It’s A Sin [above]. “My mother was also born in Swansea, so I absolutely connected with Colin and his story. Russell T Davies really created these characters that are real.”

When Jonathan saw men living with HIV die during a trial for antiretroviral drug AZT in the late 1980s, he refused to take part. “They gave three grams of AZT a day, and it killed people. It was a failed chemotherapy drug, and while it wiped out the cancer, it also wiped out your immune system.”

“I know some people were desperate, and I loved life, but I didn’t fancy that drug.”

Over the next few years Jonathan repeatedly experienced shingles and herpes, so was put on strong antibiotics for a number of years – until his health gave out in 1996.

“By then I had absolutely no energy – I would peel myself out of bed onto the sofa, and then back to bed, it was ridiculous. Eventually my doctor, Chris, started me on combination therapy.”

It wasn’t until the fourth week of treatment that Jonathan felt the effects of the treatment – describing his sudden surge of energy as “Lazarus raised from the dead”. After a year he began experiencing the side effects of the drugs and was diagnosed with drug-induced peripheral neuropathy, a condition he has for life.

“I was taken off them and now I take a Gabapentin three times a day, as well as Acetyl-L which helps with the damaged nerve endings. Since viral load testing came out in 1997 I’ve been on a number of drug regimes.”

But Jonathan acknowledges that compared to others, he’s had an easier ride, mentioning he has a friend who was diagnosed with HIV around the same time and has survived four bouts of cancer.

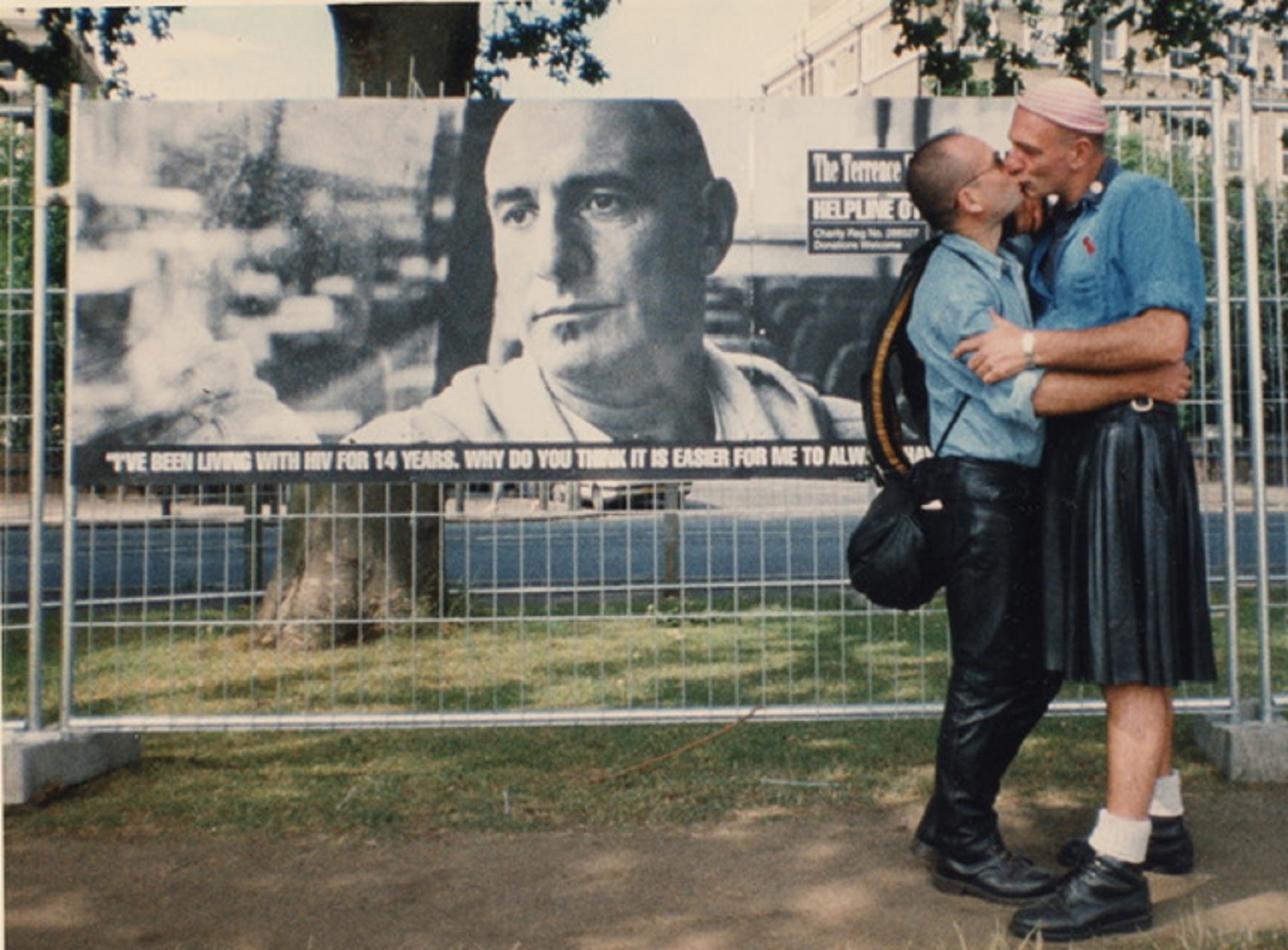

“The thing that made so much difference psychologically for me was in 2015, when U=U (Undetectable = Untransmittable) was announced. That is such a game changer – having an undetectable virus means I can’t infect anyone else. I can’t pass it on.”

“We are so lucky there is medication, and now it’s so less toxic. The changes are really phenomenal.”

But the health impacts of the virus are only one side of the coin. People living with HIV have historically faced stigma and discrimination for years, which Jonathan believes is portrayed well in It’s A Sin.

“We had no rights… The way families treated lovers and partners was awful. People were thrown out of flats they’d shared for years and just lost everything.”

“The very existence of Section 28 for example, was appalling. What that did in terms of preventing young people from receiving inclusive sex education.”

In It’s A Sin, a scene where Jill obsessively cleans and eventually destroys a mug used by Gloria, a character living with HIV reminds Jonathan of his own experiences.

“I had a very dear friend kept a special set of cutlery for whenever I went round to eat. That cutlery was just for me, nobody else. We’re still friends now – but I had it out with her!’

“The only way to destigmatise HIV is for people to talk. Like how I’m talking now, like Gareth Thomas’ amazing TV programme he made about his journey.“

“People need to talk about their experiences without shame, so it normalises HIV. It needs to be done across communities – because HIV doesn’t only affect gay men. We need Black African people to share their stories, for women to share their stories.”

“Nobody is pilloried for having Covid-19. Nobody should be pilloried for having HIV. It’s a virus, and a virus can affect anybody.”

In addition to amplifying the stories of people living with HIV, Jonathan is calling for the history of the AIDS crisis to be included in the national curriculum. “That’s one of the sadnesses, that our history isn’t taught. It’s so important that young people understand all the battles we’ve been through.

“If it wasn’t for the community, the Rupert Whitakers and so forth, we wouldn’t have the things like the Terrence Higgins Trust, the Body Positives. All of these things were initially set up by gay men and their allies, like the lesbians. They were amazing.”

Now the It’s A Sin’s run has ended, Jonathan wants this momentum to continue, especially as our life-changing goal of zero HIV transmissions by 2030 is now only nine years away.

“It’s A Sin has come at a perfect time, and now the push to 2030 needs to become a focus for everybody. We need to make sure HIV is never ‘manageable’. Manageable is never enough. We need to eradicate.”

“The biggest thing I want people to take away from It’s A Sin is testing. Know your status, don’t be afraid. We have the medication available, and if you’re diagnosed with HIV today, it’s not a death sentence anymore.”

“You’ve only got one life, so you have to just go for it.”

Terrence Higgins Trust’s advice line THT Direct can provide support around anything relating to HIV and sexual health.

Read the Attitude April Style issue, out now to download and to order globally.

Subscribe in print and get your first three issues for just £1 each, or digitally for just over £1.50 per issue.