From the Legacy Virus to Iceman: A brief history of X-Men’s LGBTQ evolution

Over half a century, the Marvel comic series has successfully turned queer subtext into queer representation, writes Juno Dawson.

By Will Stroude

Let’s get the Ex-Man joke out of the way up front. Great. Now, moving on, the queer subtext of Marvel’s long-running X-Men series is pretty much text at this stage.

Spanning comic books, video games, cartoons and countless Hollywood movies — including the latest, Dark Phoenix — the franchise features numerous genetic “mutants” with superpowers negotiating life as a much-hated minority group.

Their powers often become evident at puberty and they’re even called “Homo Superior.” I mean, come on.

When Stan Lee (RIP) launched the X-Men in 1963, he said it was partly inspired by the civil rights movement in the USA at the time – but as the 20th century progressed, it feels as if the queer metaphor increasingly became more fitting.

Main characters Professor Xavier and Magneto have different approaches to being oppressed and marginalised: Professor X believes humans and mutants can live together harmoniously, while Magneto, with his much darker past, thinks mutants, as the more powerful, should overthrow their human oppressors. In short: how much should LGBTQ people have to grovel for acceptance in society?

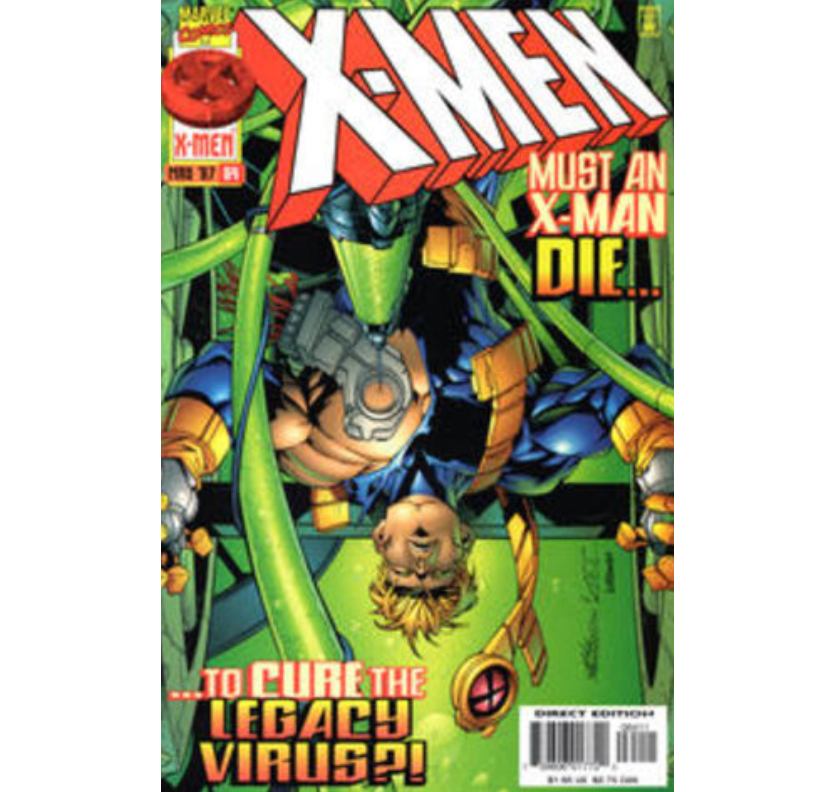

The metaphor became even more explicit as the comic book moved into the 1990s and the “Legacy Virus” storyline began. This depicted a illness which only infected mutants, leaving them with leprosy-like symptoms.

When a human character, Dr Moira MacTaggert, was eventually diagnosed, the authorities promptly found a cure. Hopefully, I don’t need to spell out that this is a pretty on-the-nose allegory of the Aids crisis.

I came to X-Men via the Nineties cartoon series (the one with the amazing theme tune). I’m not sure I dwelled too much on the subtext, but this was a superhero team with as many women as men.

Superman, Batman and others felt very macho, very male. I, as a young queer, saw Storm, Rogue and Jean Grey as sexy, powerful and smart, albeit dressed in outfits that would give you thrush.

Movie X2 (or X-Men 2 or X-Men United, depending on where you’re from) addressed the long-held gay metaphor head-on in a scene in which Bobby (Iceman) Drake has to “come out” as a mutant to his parents, who previously thought he was away at a regular boarding school. “Have you tried not being a mutant?” asks his forlorn mother.

X-Men: The Last Stand then asks if you would “cure” yourself of being a “mutant”, if you could.

The queer themes finally became explicitly queer storylines in 1992 when the first gay mutant, Nothstar, came out (although he did immediately develop the Aids metaphor, so not ideal). Much, much later — in 2009 — Shatterstar and Rictor shared the first same-sex snog in comic-book history.

Then, in 2015, Jean Grey read Iceman’s mind and outed him as gay. Not ideal, but Iceman has been living his best possible life since. Another comic book line-up worth mentioning is in the most recent Young Avengers, which is almost all queer in some way.

Comic books have always been a safe space for marginalised young people: it’s wonderful that LGBTQ readers no longer need to read between the lines.