How homophobia claimed the life and career of Justin Fashanu, the world’s first openly gay footballer

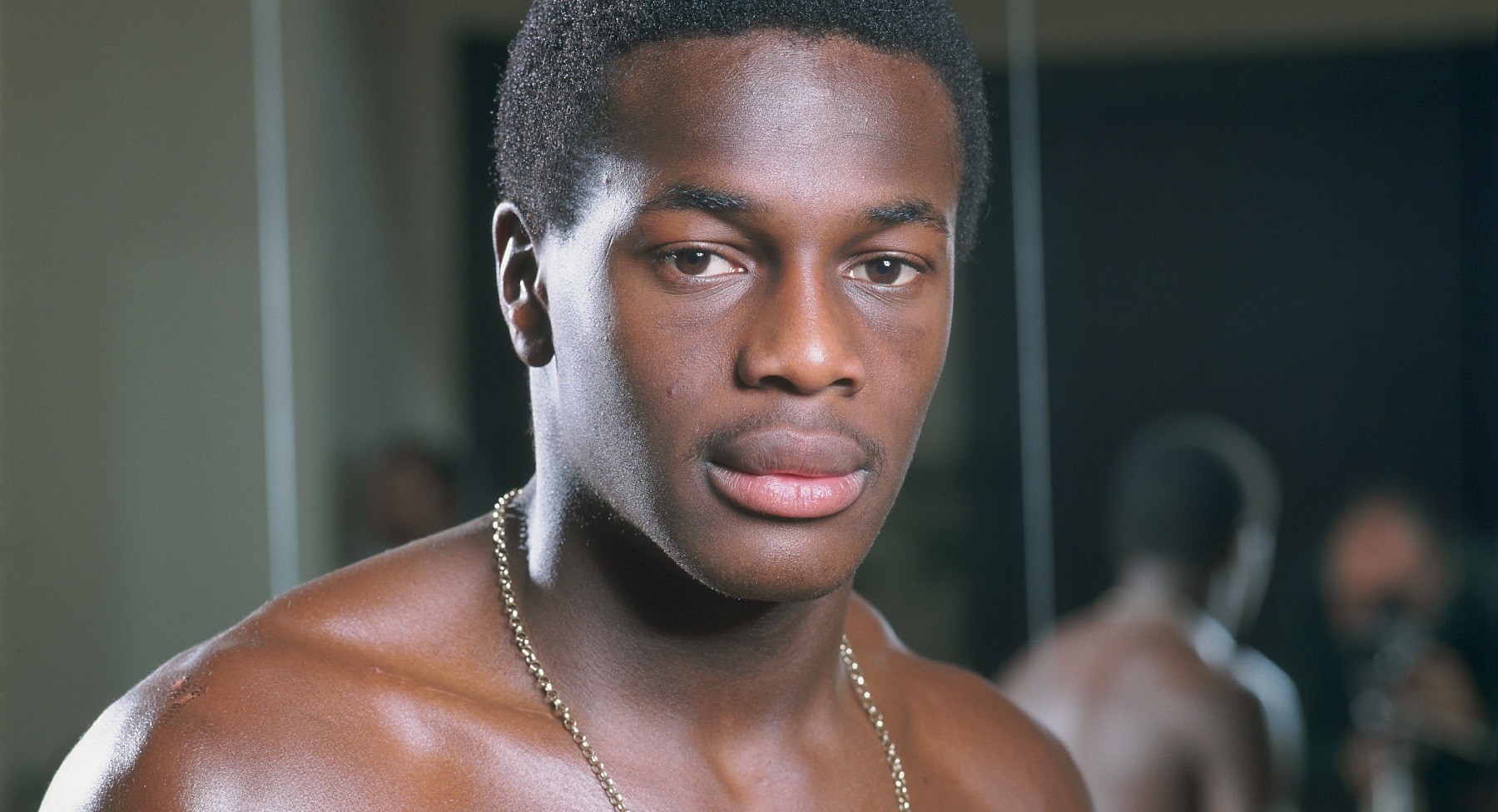

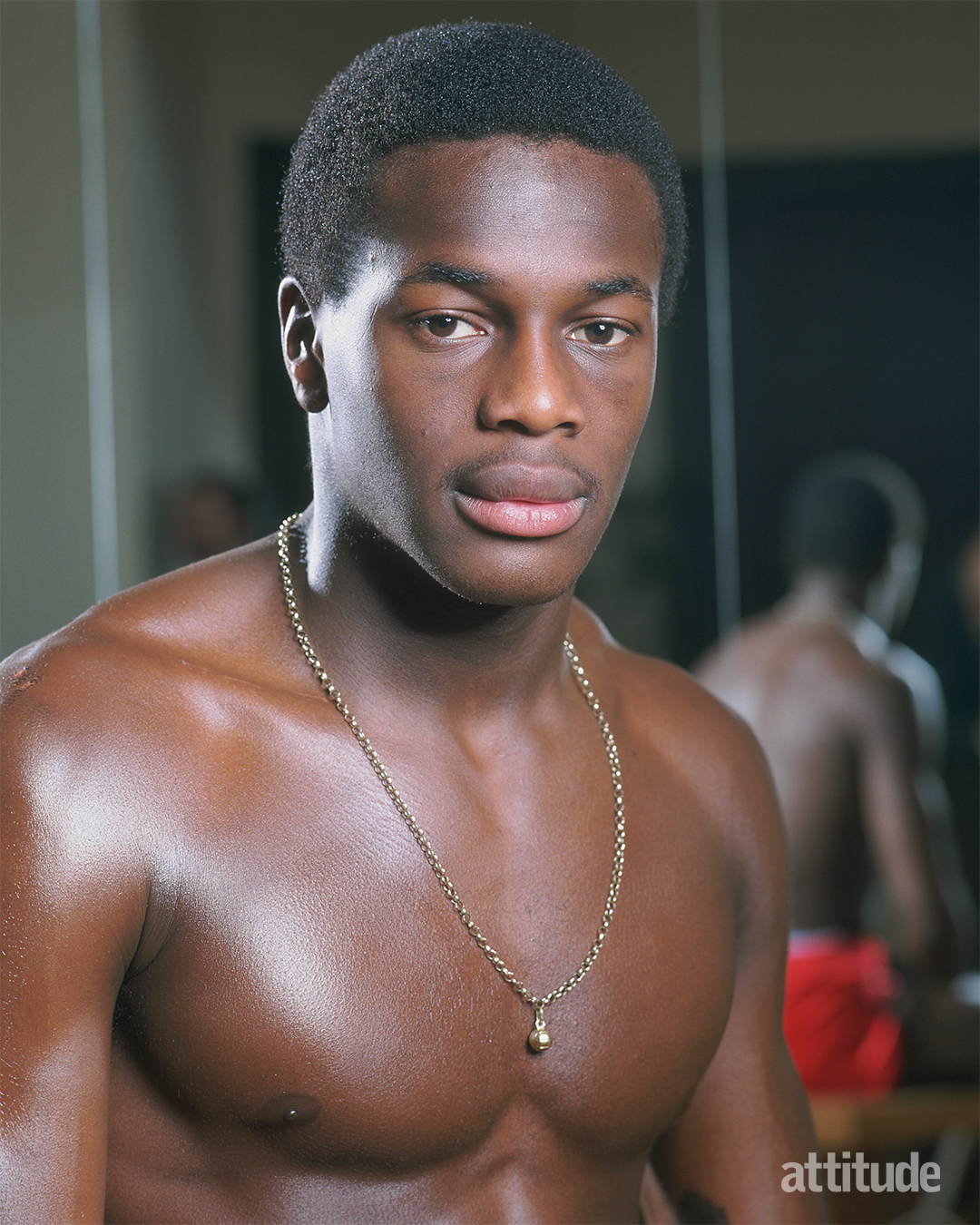

30 years after Justin Fashanu came out publicly to the world, former friend Peter Tatchell reflects on the late sportsman's complicated legacy.

By Will Stroude

Words: Peter Tatchell

Thirty years ago, on 22 October 1990, Justin Fashanu became the world’s first professional footballer to come out as gay. To this day, he’s the UK’s only top-tier male football star to declare his homosexuality while playing in this country. At the time, he said he knew 12 other Premier League footballers who were gay or bisexual. None followed his example of openness, then or since.

Justin was also the first black player to be bought by a club for £1 million and the first prominent black person in Britain to come out as LGBT+. Other black personalities, including the singer Labi Siffre, artist and film-maker Isaac Julien and Lambeth Council leader Linda Bellos, had already come out, but they didn’t have Justin’s high profile and national recognition.

Justin came out in The Sun newspaper, under the headline “£1m soccer star: I am GAY”. He said he wanted to stop “living a lie”. His otherwise dignified and courageous article was marred by titillating tales of sex with a married MP, romps in the House of Commons, and affairs with pop singers, TV stars and other footballers.

It was also tainted by the fact that he sold his story for a huge pile of money, reputedly £70,000 or more. He subsequently admitted that elements of his story were embellished because, in his words, he was “under pressure” from the paper to give them sensational gossip.

A week later, his brother, fellow footballer John Fashanu, disowned Justin in the black newspaper, The Voice. “John Fashanu: My gay brother is an outcast” screamed the headline. John later admitted to offering Justin £75,000 to stay quiet and keep his sexuality secret.

He told the Daily Mirror: “I begged him, I threatened him, I did everything I could possibly do to try and stop him coming out… I gave him the money because I didn’t want the embarrassment for me or my family.”

John later expressed regret about his behaviour. However, he continued to disrespect his brother’s memory when he claimed in a 2012 interview with talkSPORT radio that his brother was not gay but merely a fame-obsessed attention-seeker.

Justin told me he was heartbroken by the “terrible” things John said about him. He never got over what he saw as betrayal by a brother he loved.

The reaction of the wider black community was just as bad. His coming out was condemned by The Voice as “an affront to the black community… damaging… pathetic and unforgivable”.

“We heteros”, wrote Voice columnist Tony Sewell, “are sick and tired of tortured queens playing hide-and-seek around their closets. Homosexuals are the greatest queer-bashers around. No other group of people are so preoccupied with making their own sexuality look dirty.” Sewell only very recently apologised for those comments.

“Even if Fashanu had chosen to come out in The Voice rather than The Sun, I doubt his reception would have been any more sympathetic,” noted media columnist Terry Sanderson, soon afterwards. “Rejection by his own community was profoundly damaging to him.”

Although Justin later said that he “never once regretted” coming out, the hostile reaction from many in the black community hurt him deeply. He told me that since black people knew the pain of racial prejudice and discrimination, he expected they’d be understanding and supportive. Some were, but many denounced him for bringing “shame” on them.

As far as I recall, not a single black public figure supported his coming out or condemned The Voice and others in the community who had trashed him. Justin later told The Voice: “Those who say that you can’t be black, gay and proud of it are ignorant.”

Nevertheless, there were moments during his coming-out saga when he confessed that he felt “incredibly, almost suicidally, lonely”.

Justin faced a lot of criticism for choosing to come out in the right-wing, homophobic Sun newspaper, which many black people also regarded as racist. Justin responded by saying that his fans read the tabloids, not the Sunday Times. By coming out in The Sun, he hoped its reporters would cease hounding him: “I genuinely thought that if I came out in the worst newspapers and remained strong and positive about being gay, there would be nothing more that they could say.”

Some people say the press knew Justin was gay and were planning to out him. He supposedly struck a deal with The Sun to pre-empt this: “So my sexuality could be revealed on my terms,” he told me.

However, in the book, Stonewall 25, Justin claimed that he came out because he was distressed by the tragedy of a 17-year-old gay friend who had been forced out of his family home by homophobic parents, and who subsequently committed suicide: “I felt angry at the waste of his life and guilty because I had not been able to help him. I wanted to do something positive to stop such deaths happening again, so I decided to set an example and come out in the papers.”

Whatever the true reason for him coming out, one thing is certain: he wasn’t fully prepared for the backlash and the “heavy damage” it would inflict on his football career. He got homophobic abuse from fans, and few clubs were willing to sign him given his diminishing goal-scoring abilities.

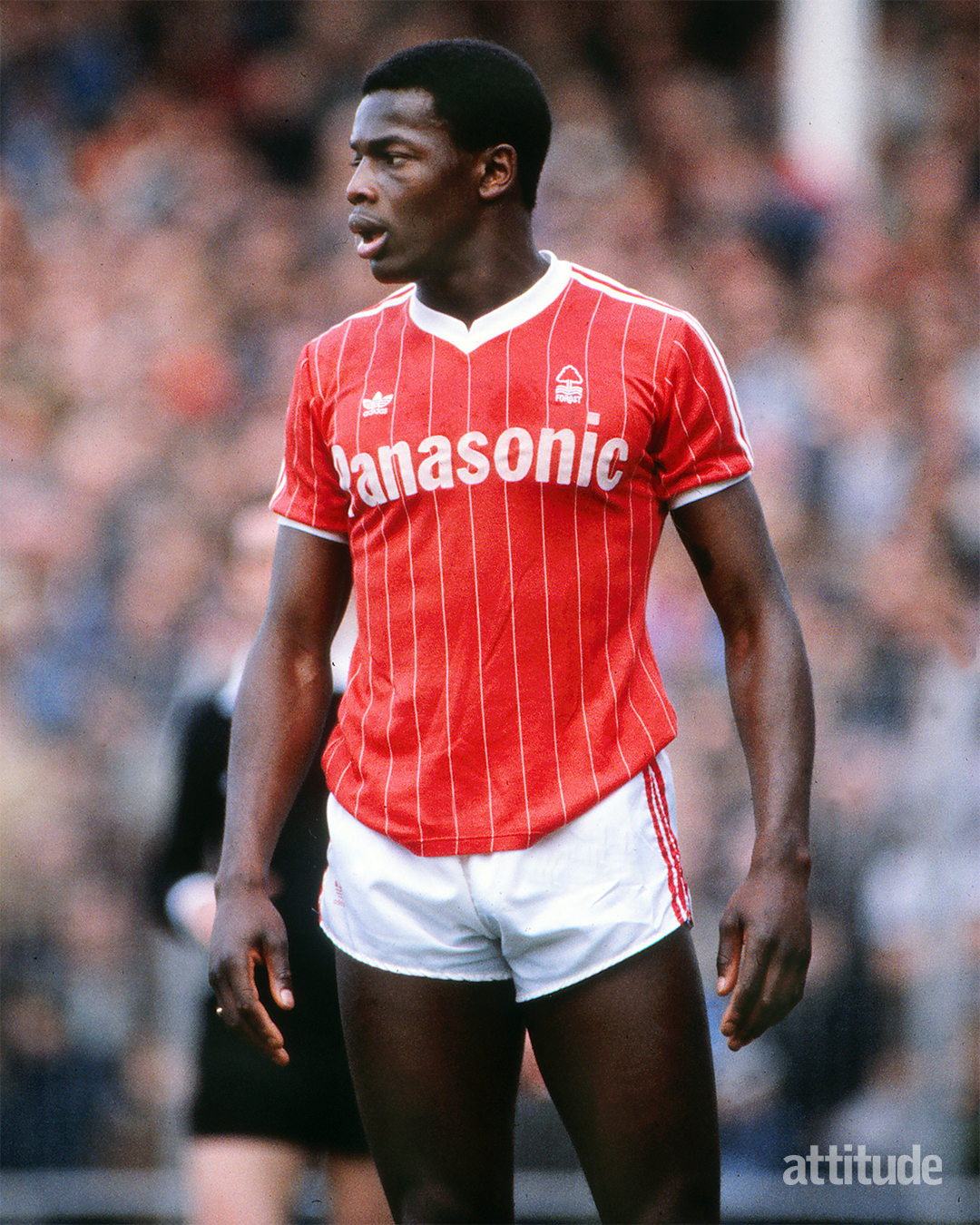

This was a far cry from his glittering football debut. In 1980, aged 19, Justin was signed to Nottingham Forest football club for £1 million. The expectations were huge. There was the pressure to deliver goals and to become a black spokesperson. He found his sudden celebrity status both a blessing and a great burden.

Justin was closeted back then and found it immensely difficult to be gay in the macho, straight world of football — not to mention the stress of living a secret gay life while under the glare of the media spotlight.

Like many black footballers in those days, he was subjected to racist taunts by fans from rival teams. They would make monkey noises and gestures, and throw bananas onto the pitch. But it was anti-gay prejudice that ultimately dragged him down.

“A bloody poof!” That’s how his manager at Nottingham Forest, Brian Clough, described his star player. Although Justin laughed them off, Clough’s sneers hurt inside, making it hard for him to concentrate on playing ‘the beautiful game’.

Justin and I met at the London gay nightclub Heaven in 1981, soon after he realised he was gay. I had been selected as the Labour parliamentary candidate for Bermondsey. We became close friends.

Justin confided to me about the problems he was having at Nottingham Forest. “Clough doesn’t respect or support me,” he complained more than once.

In his autobiography, Clough recounts a dressing-down he gave Justin after hearing rumours that he was going to gay bars: “’Where do you go if you want a loaf of bread?’ I asked him. ‘A baker’s, I suppose.’ ‘Where do you go if you want a leg of lamb?’ ‘A butcher’s.’ ‘So why do you keep going to that bloody poofs’ club?’”

Sadly, the clash with Clough turned from bad to worse. Justin’s performance went into a tail-spin. Desperate for emotional reassurance, he turned to evangelical Christianity, which further screwed up his life. With his church damning homosexuality, he became conflicted and stressed. Desperate attempts at relationships with women failed. While publicly proclaiming Christian celibacy, he ended up resorting to furtive gay sex. This made it impossible for him to have a stable same-sex relationship.

Caught between God and gayness, he suffered intense emotional and psychological turmoil.

Justin became erratic and unpredictable, both on and off the pitch. His sometimes bizarre, indefensible behaviour can only be fully understood in the context of a potentially brilliant football career cut short, largely by homophobia. He became trapped in a downward spiral of declining football prowess, bad debts, unreliability, false claims about sexual affairs with politicians and soap stars and desertion of long-standing friends, including me.

By the late 1990s, Justin had embarked on a new career coaching the US football team, Maryland Mania. Hopes of a fresh start were shattered in April 1998 when he was accused of sexual assault of a 17-year-old youth. Claiming he would not get a fair trial, he fled back to Britain. On 3 May, he was found hanged in a deserted lock-up garage in London.

His suicide note denied the charges, claiming that the sex was consensual and that he was being blackmailed by his accuser. Part of the note read: “I realised that I had already been presumed guilty. I do not want to give any more embarrassment to my friends and family.”

Whatever the truth about these allegations, Justin had — like all of us — his share of failings. Without excusing these mistakes, they were the culmination of a lifetime of rejection that began when, as a young boy, he was given up by his mother and put in a Barnardo’s children’s home.

Despite all the rejection he endured, Justin had a remarkable, praiseworthy capacity for forgiveness. Talking of the hurt inflicted on him by others, and acknowledging his own errors of judgement, Fashanu wrote in 1994: “I don’t think you ever forget those mistakes, or the mistakes that other people make that wound you, but it is important to forgive.”

Justin Fashanu was a trailblazing star – he was not flawless, but a star nonetheless.

Peter Tatchell is director of the Peter Tatchell Foundation petertatchellfoundation.org