George Takei on Star Trek, Allegiance and the biggest regret of his life

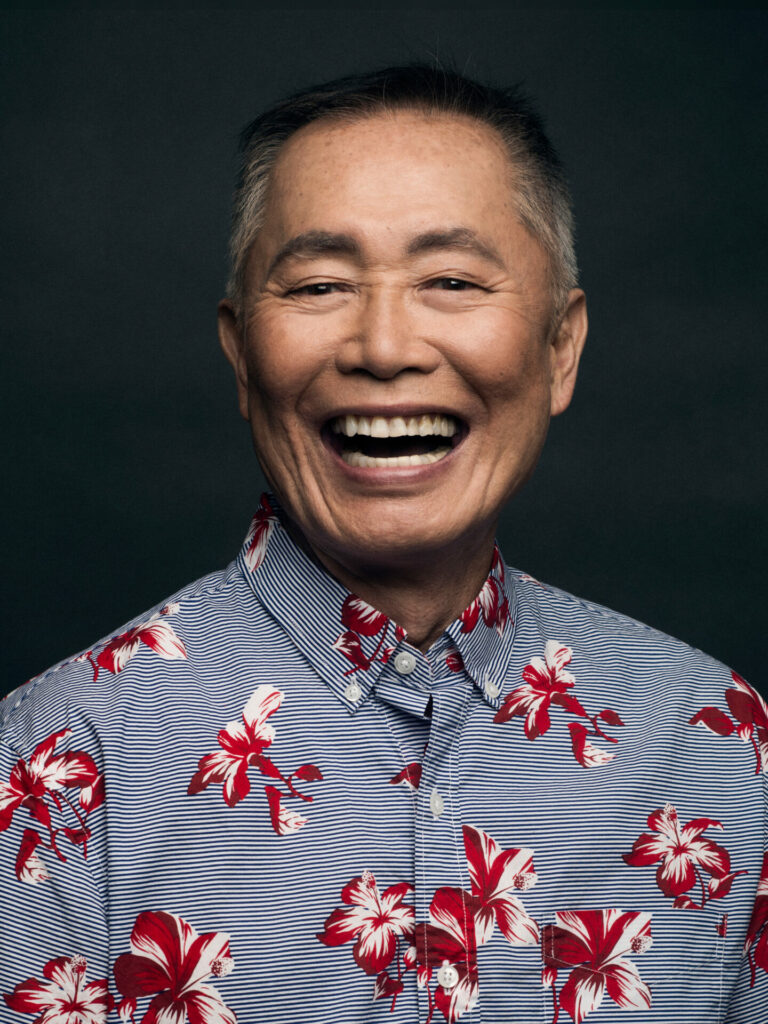

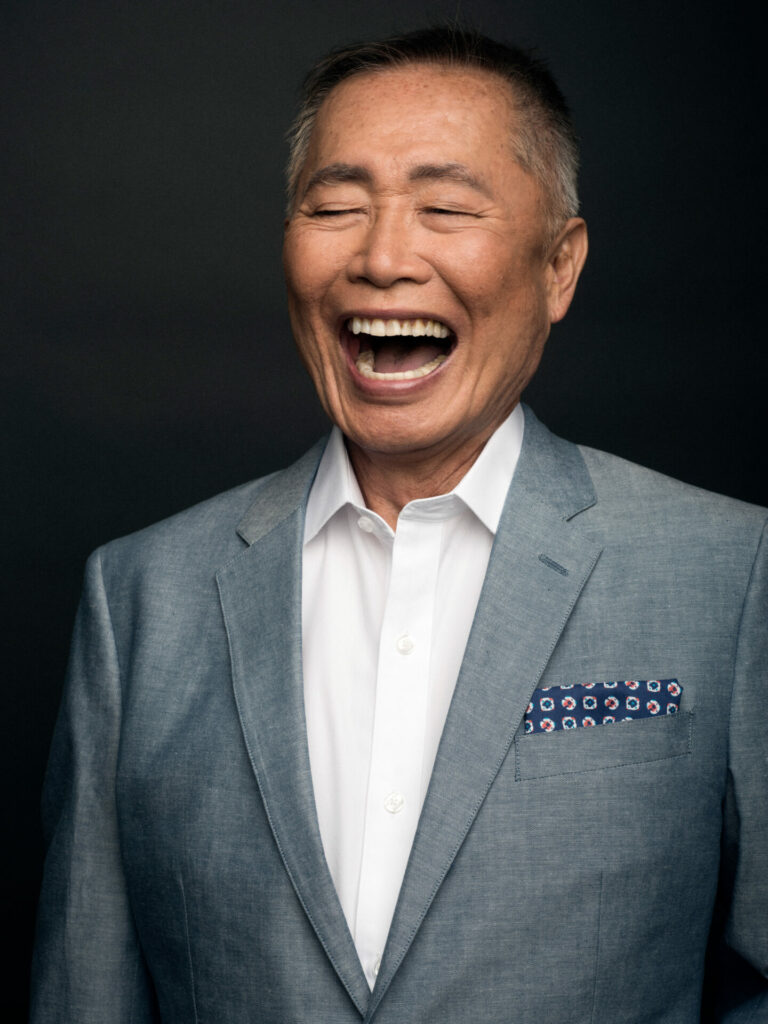

Exclusive: Ahead of his West End, gorgeous George talks getting older, keeping fit and "having the vanity to try to maintain my desirability!"

“I do 100 push-ups every morning,” reveals 85-year-old George Takei, causing this 36-year-old interviewer (with dismal upper body strength) to gasp audibly. “You’ve got to,” he adds. “The more you age, the more your muscles atrophy. Strength training is important.”

We’d be fools not to ask George for his tips on ageing gracefully. Not only is he as handsome as he was in 1966, when he first boldly went where no man had gone before as Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu on Star Trek, but he’s almost as fit, too. In January 2023, for example, he’ll take on a West End stage run — a physically gruelling challenge for an actor of any age — in Allegiance, a musical partly based on his own life. “I’m a fish and fall person: lots of vegetables and fruits,” he continues. “Be prudent with alcohol. Green tea has lots of antioxidants. It’s the usual, boring things: eat, exercise, sleep properly.”

We’ve heard it all before, sure. But delivered in his rich, wise voice, via Zoom from his LA home, George’s advice sounds like scripture. We want it tattooed onto our bodies, so we never forget it. Then again, are we simply perpetuating our youth-obsessed culture with our line of questioning? Is ageism among gay men something that’s visible to George? “Oh, yes. And when I was young, I had that attitude!” he admits with a chuckle, and refreshing honesty. “But now I’m in that category — an octogenarian, slap bang in the middle, 85 — I say: thank God I have the vanity to try to maintain my desirability!”

“If we aren’t able to deal with our home, this planet, how responsibly will we behave out there?”

George on space exploration

Amen to that. It’s not just George’s looks we want; it’s his whole life. The social media mastery (his top tip: “just be yourself”), the engaging political commentary (“see the human comedy in serious situations”) and the general zest for life which, for example, saw him take a zero-gravity flight in 2016.

“It was a sensational feeling — liberating and joyful!” he recalls. “Going up, gravity feels like a three-tonne weight on you. Then your legs are up in the air!” He’d be a shoo-in for a galactic PR stunt, but space exploration “requires the fittest of humankind. I’m realistic. I’m past that point. I feel my aches and pains, my pops in my joints. I am who I am.”

Where does he stand on star-trekking generally? “We’ve bespoiled this planet,” he notes. “It was predicted. Now we’re in it. Horrific hurricanes and firestorms. My home is southern California. We’ve been in a 10-year drought and are legally forbidden to water our lawns more than twice a week. Brown lawns are the landscape in our neighbourhood. If we aren’t able to deal with our home, our habitat, this planet, how responsibly will we behave out there? But, at the same time, there’s that unquenchable curiosity.”

Brown lawns aside, George’s happy home life is also something we hope to emulate. Look up red-carpet photos of him and hubby Brad Altman: they positively beam in each other’s company. Few Hollywood couples appear quite so devoted to one another. They wed in 2008 — the year George charmed the pants off the British public and finished third on I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! — after meeting decades before through gay running club, the LA Frontrunners. “It was poetry, the way he ran,” recalls George. “Graceful, those strides. He was — no longer is — a great runner. He indeed was a frontrunner. I’m in the middle.”

The 80s must have been an interesting time for the then-40-something. Publicly, he was a straight-presenting, globally famous movie star, appearing in four Star Trek films in that decade alone. (When I admit I’m a franchise novice, he takes it with good humour. “I’m shattered people like you exist. Such a sheltered life! How did you manage, to this day? You look otherwise normal!”) Privately, he was a gay man forging connections in an era when, one assumes and romanticises, mutual assured discretion and respect among LGBTQs was a prerequisite in the days before a celebrity’s every move was immediately plastered across social media.

“Every part of my life was closeted — but running,” George tells me. “In those days, we had free newspapers with local businesses advertising on it. I picked one up in a gay bar and there was an article on a gay running club. I thought: ‘I love running! Should I? Shouldn’t I? They’re running out in public… A gay bar is within walls!’ Sure enough, when I went out for my first run along a reservoir, there was this whispering… The club president said: ‘I want to introduce you — what’s your name? They’re whispering about you, but I don’t know who you are!’” The guys invited George out for breakfast afterwards and… well, you can just picture it, can’t you? What’s the 80s equivalent of avocado toast?

Prior to that, there was at least one person in his professional sphere George trusted enough to address the subject of queerness: Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. The show dealt, metaphorically, with “all the volatile issues of the time. The Vietnam War. The civil rights movement. But not LGBTQ equality. In a very private conversation, I told him: ‘We should, metaphorically, address LGBTQ equality.’ Gene understood very much.”

The screenwriter, however, pointed to the 1968 Star Trek episode ‘Plato’s Stepchildren’, in which Uhura (played by Black actress Nichelle Nichols) famously kissed Captain Kirk (played by white actor William Shatner). The first Black-white kiss on American network TV was “ground-breaking” remembers George. “But that show got the lowest rating we ever had, because stations in the American South refused to air it. Gene said: ‘I’ve got to stay on the air to address the issues I am addressing. Some issues would be so volatile, you could be cancelled. I have a red line.’ I understood that.”

Publicly, George came out “roaring” in 2005, in response to movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger, then-governor of California, vetoing marriage equality. “When he ran for governor, he ran saying: ‘I’m from Hollywood, I’ve worked with gays and lesbians, some of my friends are gays and lesbians’ — that campaign rhetoric.” George is still visibly annoyed over what went down. “Some of my LGBTQ friends thought he’d sign, be what he campaigned as. I did not. I was suspicious. When the marriage equality bill landed on his desk, he vetoed it. I was so angry that I spoke to the press for the first time as a gay man, blasting his veto.”

Has he run into Schwarzenegger since? “Never have. Don’t want to. Don’t trust him.” Hasta la vista, baby — or rather, not.

With both the library and the closet door officially open, George entered a new stage in his career, scoring high-profile guest spots as himself on Malcolm in the Middle and Will & Grace. “When I did come out, I was fully prepared to retire from my acting career,” he admits. “It turned out to be the reverse. I was surprised.” In 2016, he made his fifth guest appearance on The Simpsons — for the first time as himself.

His career reached a new creative peak with Allegiance, which premiered in San Diego in 2012 and played on Broadway from 2015-2016. The show’s historical backdrop is the Japanese-American internment of the Second World War, which followed Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order forcibly relocating and imprisoning 125,000 Japanese-Americans — George’s family among them — fearing them loyal to the Empire of Japan. Along with his parents, brother and sister, George was forced to live in a single horse stall in Californian racetrack Santa Anita Park, which had been set up as a temporary detention centre, before being sent to an internment centre in Rohwer, Arkansas, where he lived surrounded by barbed wire. (Although Allegiance focuses on the Kimura family, it is inspired by George’s story.)

“They categorised us as enemy aliens, just because of our ancestry and race,” he says. “We were neither. We were Americans of Japanese ancestry. Not aliens, not enemies. Right after Pearl Harbor, young Japanese-Americans, like all young Americans, rushed to recruitment centres to volunteer to serve in the US military. This was an act of patriotism that was served a slap in the face. They were denied military service, categorised as enemy aliens and imprisoned. They froze our bank account, our money was taken, we were financially straitjacketed; they took everything from us, impoverished and imprisoned us.”

George has previously shared the harrowing memory of five bayonet-wielding soldiers arriving on his LA driveway to round up the family when he was just five years old. (Is his earliest memory, I ask hopefully, of something happier? He replies: “It’s amazing what I’m able to describe of the bedroom my brother Henry and I shared, of my babyhood. My mother used to take me on stroller walks down Wilshire Boulevard in LA. I remember a sculpture of a woman, like a ship’s mast, water spraying on her, by a driveway.” It turns out to be The Ambassador Hotel, where Bobby Kennedy was shot.)

Reading up on George’s story, and the plot of the play, it strikes me that, decades later, we’re still seeing headlines about children being separated from parents at borders, about the impact of Brexit on immigration, of plans to deport asylum seekers arriving in the UK to Rwanda. Does George have faith, after everything, that humankind will one day learn to coexist peacefully?

“This kind of irrationality goes in cycles,” he opines. “Pearl Harbor was the trigger to the horrific events that followed. After 9/11, the same kind of hysteria, madness and prejudice existed. We had a president who tried to get a Muslim travel ban passed [in 2017]. He had great difficulty, because when he signed the first one, the Deputy Attorney General, Sally Yates, said: ‘I will not defend this.’ He had to try three times before it was approved. I cling to that as: we learned something. But when Pearl Harbor was bombed, it was all government leadership swept up by hysteria. The Attorney General, the Secretary of State, everybody.

Even an organisation like the American Civil Liberties Union, famous for having the courage to stand up against the violation of fundamental civil liberties in the US, took a neutral stance. Only one chapter had the courage to say: ‘This is unjust, we’ll fight,’ and that was the San Francisco chapter, and my personal hero: Wayne Collins. He’s the attorney that fought for Japanese-Americans.”

George’s other hero is his father, Takekuma Norman Takei, who died in 1979. “He guided me through my teen years when I was imprisoned by my own government,” he says. “Was my guide, teacher and loving father throughout my life, and yet I didn’t have the guts to come out to him at all. He passed before I was able to. He was under such pressure; he spoke Japanese and English fluently. All three camps we were in, he was elected block manager — more or less the representative for our block — to communicate with the camp command.

He always made speeches at mealtime. Many young people were radicalised. Their attitude was: ‘The government is going to call me an enemy. God damn it, I’m going to show you what kind of enemy I can be to you!’ Those rabble-rousing were saying: ‘I’m going to be loyal to Japan. Bonsai! Bonsai!’ Under all that swirling amongst our people, he was able to talk rationally and calm down people who were burning with rage.”

George’s mother, Fumiko Emily Takei, died in 2002. “By the time I was together with Brad, my mother knew him as my good friend,” he explains. “She didn’t drive, so I’d drive her places. Sometimes I couldn’t, and Brad volunteered. So, she knew him and loved him as my friend. It became naturalised. ‘Oh, George’s friend is living with him.’ So it was a natural transition with my mother. But it’s been the great regret of my life that I never came out to the man who I loved so much: my father.”

I then thank George on behalf of Attitude, for being a spiritual father to our community, when so many of our own fathers and grandfathers have eschewed supporting their LGBTQ children, and so many of our queer elders have been sadly lost to HIV and Aids. “I understand your position,” he says with great kindness, before reflecting further on his childhood.

“Many Japanese-American parents of my father’s generation did not talk to their children about their imprisonment,” George says. “Because it was so painful and degrading. They didn’t want to inflict that pain on their children. Understandable.”

George’s dad was an exception. Some Japanese-Americans know very little about their own family history, George adds. “On Broadway, they’d come backstage to tell me how deeply moved they were by the play, telling me their parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts were in the internment community. I’d ask, which camp? Arkansas? Wyoming? Colorado? Idaho?’ Their faces were blank. My mission isn’t just to make America understand that chapter of its history, but Japanese-Americans to know something of their own family history.”

I tell George that his description of his dad as strong, level-headed and willing to face reality suggests he would have understood his son’s sexuality, had he told him.

“I want to think so,” he says with a hopeful smile.