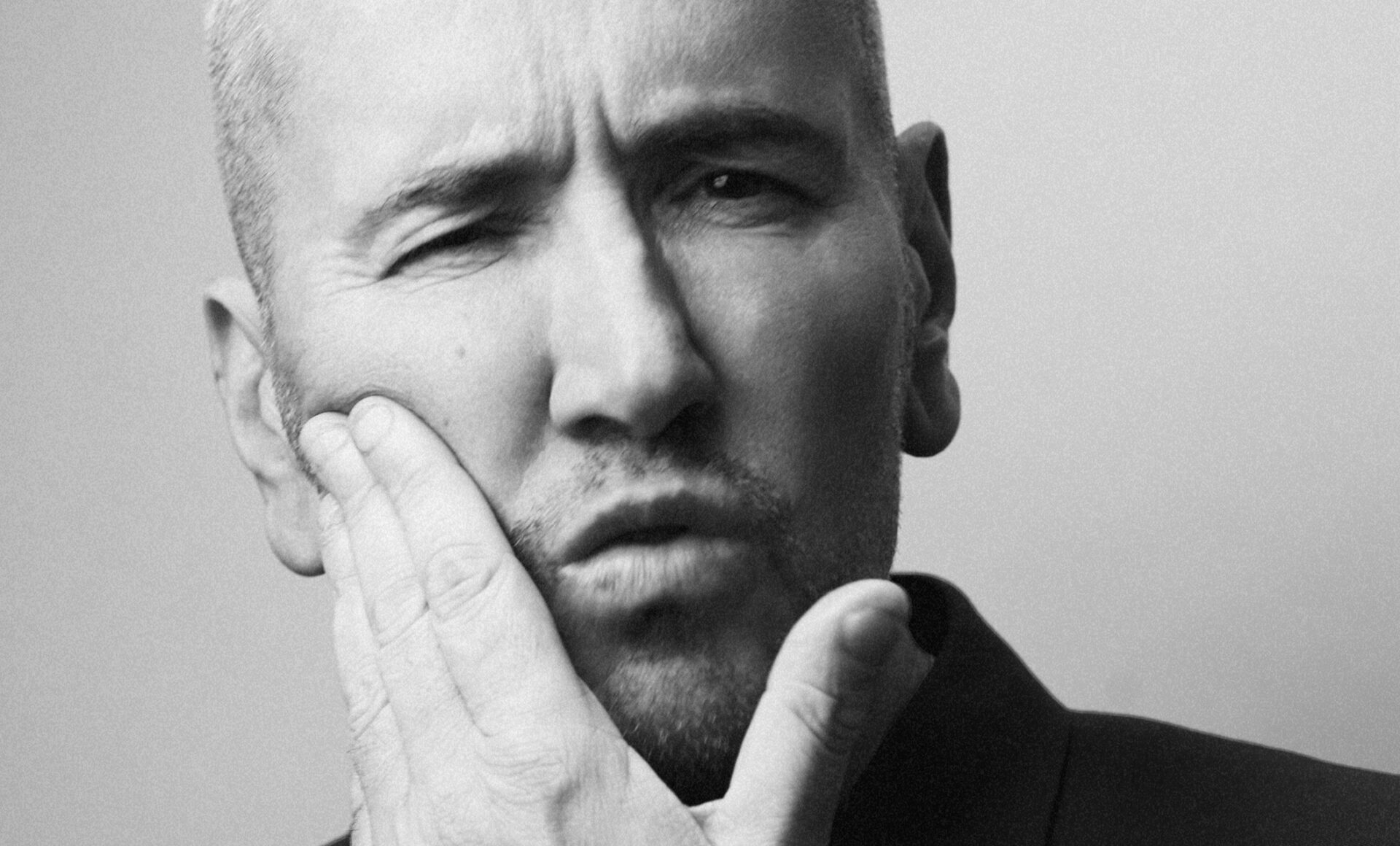

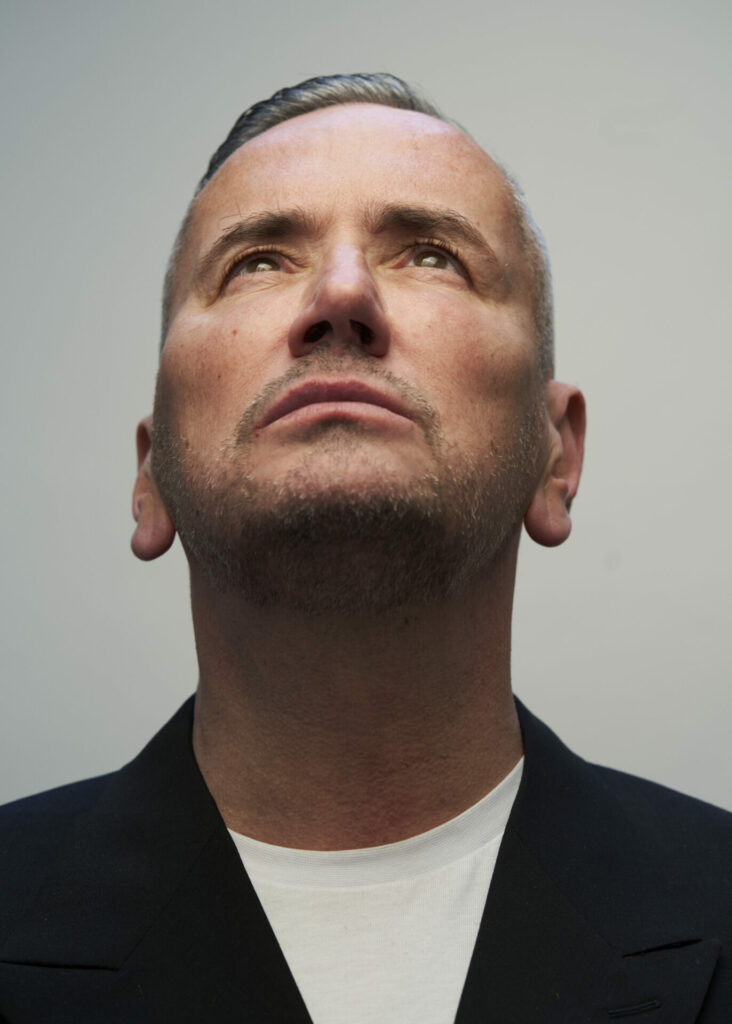

DJ Fat Tony is turning the page on a traumatic past

The winner of the Book Award shares on drug abuse, sobriety, his bestselling autobiography, I Don’t Take Requests, and finally facing his demons.

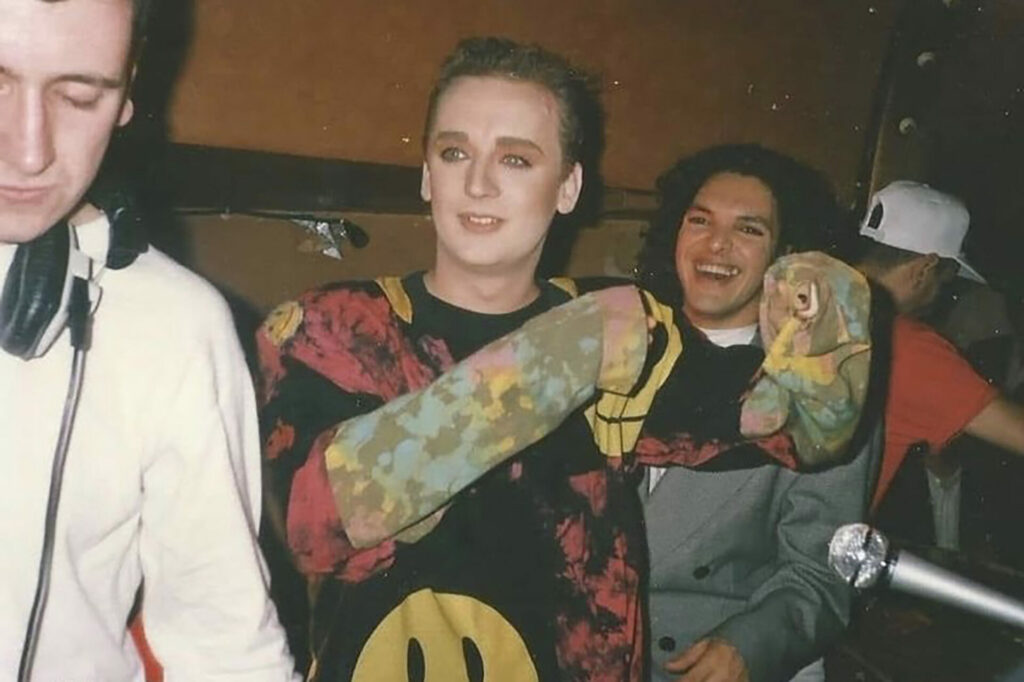

It was around the late 90s when I first met Tony Marnoch, aka DJ Fat Tony. Don’t expect me to pinpoint an exact date; all I know is that I was clubbing in my mid to late teens using a fake ID to get into Trade, which at the time was the only place open in London after hours. The infamous weekly night took over Turnmills, a long-since closed subterranean venue in Farringdon, opening its doors every Sunday morning from 4:30 am. Barely out of the closet to myself let alone the wider world, on reflection I was probably too young and naive to be navigating what was without doubt one of the UK’s most hedonistic — and now legendary — queer clubs.

A genuinely mixed bag of LGBTQ+ people flocked to Trade week in week out. It had two dancefloors: the main one spinning hard-as-nails techno and house, while Trade Lite (the smaller, second room) pioneered a funkier, more vocal sound. The latter was Fat Tony’s playground and where I found myself most weekends. Almost ritualistically, I’d enter Turnmills, descend the stairs and turn left into Trade Lite and greet Tony with a kiss on each cheek in the DJ booth as he dropped the needle on that week’s newest tunes.

He was as much a showman as he was a master-mixer on the decks. Snorting bumps of whatever drug was offered to him or sniffing poppers while delivering a flawless set became part of the Fat Tony repertoire. His nonchalant excess was synonymous with his brand as one of the gay scene’s finest DJs, and he was part of a legion of boundary-pushing pioneers in queer British culture: Leigh Bowery, Boy George, Princess Julia, Steve Strange, and too many others to mention. These innovators would become the figureheads of an unparalleled era of creative excellence, the echoes of which ripple through the LGBTQ+ scene today.

By the late 90s, Fat Tony’s ferocious lifestyle began to eat away at his career. He looked increasingly haggard, his face drawn and expressionless. One year, at Ruby — an annual event bringing together club heavyweights Trade, DTPM, and Fiction for a giant post-Pride party — Tony could barely make it through his set. At one point he stopped a record mid-play. While he was only ever friendly to me, his temper was notorious on the gay scene. He was slowly tearing himself apart.

Away from the decks, Tony became less and less coherent in conversation. The drug-ravaged, foulmouthed rants that eventually overshadowed his reputation as a fierce DJ would have more likely seen Tony awarded the prize for ‘person least likely to string a sentence together’, rather than being celebrated two decades later for publishing one of the most candid autobiographies of the year.

His life began to derail rapidly in the early 00s. During one horrific cocaine-fuelled binge, he pulled out all his teeth with pliers. Eventually, Fat Tony sought help in 2007 and entered rehab. After a gruelling five months of intense therapy and treatment, Tony stepped out into what he then thought was a new chapter in his life. But as he would discover in the years that followed, his journey had only just begun. As well as returning to DJing, Tony started to openly discuss the addiction crisis growing within the gay community, using his voice to support the work of campaigners like David Stuart and London-based LGBTQ+ addiction service Antidote to raise awareness of the complex issues around chemsex.

It was in late February 2020 that Tony’s profile exploded following a Mixmag documentary on his life that has since amassed more than seven million views. “It was at that point I thought, ‘You know what, people are really interested,’” Tony says as we talk in the conservatory of his flat in Pimlico, an oasis of calm far removed from the frantic night-time world he built a career in. “I suddenly got this platform where my profile had completely tripled.” Tony’s Instagram account now boasts more than 300K followers and mostly comprises bitingly acerbic memes mingled with the kind of life-affirming posts you’d expect from somebody who once tore their life apart before somehow pulling it back from the precipice of self-destruction. Anyone who knows him will agree that his Insta is essentially his brain curated on a digital canvas.

After almost losing it all, Tony’s career has now reached the peaks it undoubtedly would have hit had he not lost his way due to a spiralling addiction to drink and drugs. Today, he DJs for leading fashion brands, has collaborated with Adidas, plays Ibiza’s biggest clubs, and has spun records at private parties for the world’s biggest names in music, film, fashion, and TV — although he’s just as much at home DJing to a room of housewives at his Full Fat brunches. And he’s more than partial to a casual name drop, counting Elton John, Kate Moss, and Courtney Love among his closest pals… oh, and of course Claire Sweeney, who he’s got a dinner date with right after our interview.

Fundamental to Tony’s notoriety — for better or worse, I’m sure he’d agree — has always been his unabashed frankness, so when it came to telling his life story, brutal honesty was the only option. Written with admirable candour with co-author Michael Hennegan, I Don’t Take Requests was published earlier this year. It soon became a Sunday Times bestseller, and a TV adaptation is already in the works. But despite its success, writing it — for the first time openly discussing his HIV status and the sexual abuse he experienced as a child — proved more gruelling than Tony could ever have imagined, as he reveals here.

Tell me about I Don’t Take Requests.

It’s a modern-day self-help book. It’s a book of redemption, of honesty. When we started writing, I really didn’t think it was going to be life-changing in any way, shape or form. I just thought, ‘OK, this is a platform to release past trauma and to talk about that, to share that with people that would identify with it.’ Then I ended up in trauma therapy for a year to deal with the stuff that we were writing. And then when it got released, for months and months and months, I would wake up at three o’clock in the morning and think, ‘What have you done? Why have you put that in there?’ Fuck me, it was a gamble. I never talk about being HIV positive. I feel I don’t need to talk about it because I’ve dealt with it. Most of the stuff in the book, I didn’t deal with until I started writing it and then suddenly, ‘Fuck.’ Every time we got to another chapter, it was flooring [me].

At what points did you have to stop and pause?

A year in, I took three or four months off. I got to the abuse chapter. That made me really ill. And then there was the court case chapter. I thought, ‘How do you approach that?’ Suddenly, I was bringing to the surface that I was accused by a 14-year-old boy of rape, again. In a lot of people’s eyes, it’s always, ‘There’s no smoke without fire.’ And I was vindicated and held my head up high because I knew throughout all that I was innocent.

But to bring that back up for no reason when it’s no longer on Google and it’s right down the bottom [of the search page] and all of that stuff, was that necessary? And I thought, ‘You know what, it is necessary.’ Because other people go through that shit. They get accused. And in this country, we are guilty till proven innocent in everything. I wanted people to understand what I went through and how painful it was. I also wanted people to understand the magic that came out of it. At that point, I had to stop. And I started doing trauma therapy twice a week.

I really thought that I loved myself. I really thought that I actually was in an all-right place with myself and I wasn’t. I hated myself so much. I was so scared of who I really was. So, I’ve always put on this image: I’ll make you laugh; I’ll be the bitchiest; I’ll be the loudest, so that no one got to know who I really was. Through trauma therapy and writing the book, it’s made me realise I’m all right with who I am.

And who are you?

If you’d asked me to describe myself two years ago, I would have said, “I’m a lying, cheating skank.” And I was. And now I’m none of those things. I don’t have time to lie, and what I mean by that is that lying takes up so much time, so much effort and so much… It gets you to A and doesn’t get you any further. I can go from A to Z now quite easily, by telling the truth. Today, I think that I’m self-loving; I love myself, so therefore I can love other people. I believe in myself again and, most importantly, I believe in other people. It was never the case before. I would much rather someone fail than be successful because I was always jealous. And I no longer have that in me. I don’t have that ability to think of the worst for someone; I’d rather think the better for them.

There’s a perception that once you get sober, you’re healed, but actually the journey is ongoing.

As I say in the book, “You take the rum out of the fruitcake, what are you left with? Fruitcake.” And it really was the case. I was insane. The first six years of my sobriety, I was insane. Absolutely fucking mental. I thought that because I [had] put a drink and a drug down, the world had changed and I’d changed. And people used to say all the time, “He ain’t changed.” And I was like, “Yes, I have.” I’d want to fight them all.

But you know what? I wasn’t ready. I put down the drink, drugs. I wasn’t ready to get rid of sex. I was a 41-year-old man. I thought, ‘OK, I’m in my prime. Why would I want to get rid of that?’ Now, at 56, that no longer serves a purpose. Sleeping with four or five guys a day wasn’t a badge of honour or self-loving; it was self-hating. It was basically like taking drugs. It was another drug that wanted to kill me. And I was doing that for six years.

Did you have to get to the point where you had to forgive yourself as well?

You hit the nail on the head. It’s all about forgiveness. I forgive who I am. The last two chapters of the book we changed so many times, because so much had happened. Like success. Mikey [Hennegan] was like, “What do you call success?” And I was like, “Success is where I’m at in my career. Success is being able to go to bed and sleep at night. That’s success. To go to bed and know that my side of the street is clean. That’s success. To be able to pick up the phone and tell someone I love them or to actually look at someone in the face and tell them I love them and really mean it is success.”

All the other stuff falls in, comes in afterwards. Do you get what I mean? Yeah, my career is amazing right now. That’s because of the things I don’t do, not the things I do. The things I do is 10 percent of it. The 90 percent of it is the things that I don’t do any more. I don’t have to slag the world off because I slagged myself off. The past two years have just changed my life completely.

You describe those hedonistic years of the 80s and 90s in such charismatic detail in the book, it’s so alluring.

They were magical times, but they were the 80s. I couldn’t relive that now. And so therefore people go, “Do you miss that? Do you miss them?” Well, of course I miss those days. But I don’t miss that prolonged four-day night. What I miss is the feeling, the emotion that was in it and everything that went with it, and the magic that those moments in time were. But I can’t have those now. I’m having those moments, just in different ways now. They were fucking incredible and everything in that book, people go, “Do you not miss a drink?” I don’t miss drinks and I don’t miss drugs. But what I do miss is the situations they took me to: I loved the drama and the chaos. When I got sober, that was the bit I was scared of losing, so I carried it on. Always in everyone else’s business, always doing drama, always arguing with everyone. I was addicted to that drama, and now trauma therapy taught me that I don’t need to be on that.

What kind of self-care do you practise?

Affirmations are a really good one. I can wake up and feel really fat. I can wake up and feel really old. I’ve learned how to accept a weekend off work. I used to take a weekend off and I’d be on social media thinking, ‘My career’s over.’ Now, I know that I’m enough, what I’ve got is enough. Clothes, though, totally different. I never have enough clothes.

Where did that fear and anxiety stem from?

I think that it was fear of intimacy. I never ever wanted anyone to get close to me. I always suffered with imposter syndrome, where I always thought that I was a fake because I’d never really had a game plan. I never set myself goals. I never saved for anything, so I’m hardly going to save anything else. I really think that anxiety of always wanting everyone to like me was because I never ever had anyone; I didn’t believe anyone ever loved me.

Like and love are two different things. And I always wanted everyone to like me. I never ever wanted anyone to love me because I was scared of love. And that’s because I never loved myself. And now, I love myself enough to get through the day without completely and utterly annihilating it. Because before, I’d be in the perfect relationship, everything would be going great. And I would think, ‘Today’s a really good day to fuck that up and go and get caught out having anonymous sex or all of those other destructive behaviours. And they’re all learned behaviours, everything is a learned behaviour. They were coping mechanisms.

How does it feel to reflect on your time in rehab?

I was scared. I was so feared up. Any time I got scared, my coping mechanisms were to start screaming, shouting, making everyone laugh, or just being really vile. And all of those things came at once. I was a stuttering mess. [As] soon as I got in the door, it all came out because I wanted everyone to feel sorry for me. It was just pure fear. Fear that that was the end. Although I never wanted to use drugs again, I’d got to the end of the road. I just didn’t know how not to.

When you got sober, you started to be a champion for helping other gay men in the same situation when there were not many people making noise about it. Why did you want to be that person?

Because it had taken me to a point where I wanted to kill myself every day, and I came through that. I’d suddenly got this mini platform that I thought, ‘OK, I can do good here.’ I had so much to make amends for, to my own community. When I say I used drugs, I also not only used drugs, [but] I used people, and I abused people in the sense of my behaviours and the way I was with people.

So, I went out of my way to try and help in a way that I could. And we had the backlash from it, death threats. I got to go on Channel 4 News and talk about it. The next day, the amount of hate messages I got: “Who do you think you are saying that about our community?” The worst thing in the world is internalised homophobia.

We went to a police meeting. Kids were dying in police custody and they’re putting it down to teenage heart attacks. The police were taking the G[HB] off them, but they had no clue what they were doing. If you are doing G every hour, you need it on the hour, or else the heart stops beating. That’s what was happening. We were doing it to try and save lives.

What does your Attitude award mean to you?

I’m very flattered, I’m very honoured, I really am. It’s a part of my community and suddenly I’m being accepted by my community. Because for a long time I pushed myself away from everyone. And now I can accept that. If you’d offered me an award three years ago, I would’ve been, “Oh, fuck off, what’s that about?” I can accept an award now because I can accept love and I can accept praise. I could never be praised before because I always thought someone wanted something. And that comes from being a 10-year-old kid that was abused — whereas now I’d be like, “Thank you so much, that’s nice of you,” because I can accept that.

Check out DJ Fat Tony’s acceptance speech from the 2022 Virgin Atlantic Attitude Awards below:

I Don’t Take Requests by Fat Tony with Michael Hennegan is out now

The Attitude Awards issue is out now