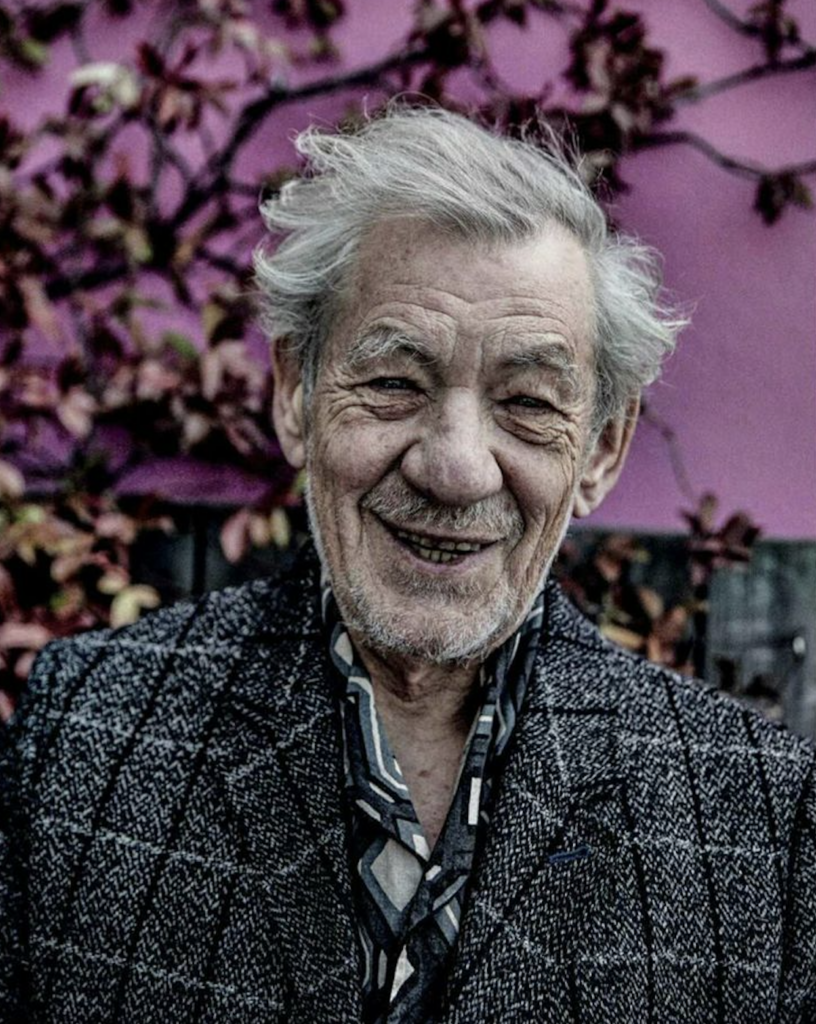

Ian McKellen on life as a gay man at 84: ‘I have crushes on people – but I don’t want them to move in, thank you’

Exclusive: As the six-time Olivier Award-winner and his co-star Roger Allam take to the London stage in “old guy, gay romcom” Frank and Percy, the pair reflect on life, love, the ageing process and Section 28

“It’s impenetrable!” bellows Sir Ian McKellen, attacking his rock-hard chocolate brownie with the gusto of Gandalf plunging his staff into the ground and declaring “You shall not pass!” His magisterial voice echoes around the (otherwise empty) Manchester restaurant in which I’m lucky enough to be dining with the national treasure for this interview. “Has this been microwaved?!” he asks aloud. Sheepish-looking waiting staff, within earshot, pretend not to hear him. This only intensifies his disdain and my laughter. I’m close enough to see the twinkle in his eye. The brownie may be impenetrable, but McKellen isn’t angry about it — he’s merely playing the role of a hilariously naughty and endlessly entertaining dinner companion. And it’s an Oscar-worthy performance.

He’s just as withering when I inform him that my fatherland, the Forest of Dean, inspired J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth, thanks to a minerally enriched patch of woodland producing thousands of surreal tree and rock formations. “There’s not a corner of the planet that doesn’t claim to be the origin of Middle Earth!” he retorts, to which I laugh out loud. (McKellen was of course Oscar-nominated for his performance as Gandalf in 2001’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, the first of Peter Jackson’s Tolkien film adaptations.)

Equally charming is our tablemate Roger Allam, star of Game of Thrones and The Thick of It, and McKellen’s co-star in Frank and Percy, a stage comedy playing at London’s The Other Palace theatre until early December. It tells the story of two strangers, both elderly men, who forge an unexpected connection while walking their dogs in a park.

“I always thought it was like an old guy, gay romcom,” says Allam, a three-time Olivier Award-winner. “Although my character isn’t gay. But discovers that he can be.”

McKellen says, “What’s interesting, having played it for seven weeks in Windsor, two in Bath, is that a perfectly straight audience is happy to take on the joy of watching two old guys make fools of themselves and fall in love. They love it. Even 10 years ago, you couldn’t have expected that. The world’s moved on. Of course, I do think theatre audiences are probably the vanguard of social change.”

“It will make a very good film,” he goes on to say. “In fact, there’s a screenplay being written as we speak. It doesn’t need much tinkering with to make it cinematic.”

Allam isn’t gay, but his irresistible real-life chemistry with McKellen is apparent throughout the evening. Their friendship began in earnest in the late 80s. McKellen had just come out publicly as gay at 48 and co-founded LGBTQ+ rights lobbying group Stonewall in protest at Margaret Thatcher’s Section 28, which banned ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools. After bumping into Allam in the lobby of a hotel, McKellen enlisted him to join a demonstration against the new law.

“I had an enormous hangover!” remembers Allam, 69, of that day. “It was in Glasgow, I think. We knew each other, but not well. He said, ‘Will you come on the march tomorrow?’ And I said, ‘Yes, of course.’ I’m very glad I did. It seemed a very natural thing to do.”

When I ask McKellen how plausible it is that a law like Section 28 could return, he gives a grave reply. “If you’d asked me that six hours ago, I’d have said no,” the 84-year-old says cryptically. “But I talked to [Stonewall co-founder] Michael Cashman, and he says things aren’t looking good. There are going to be restrictions on discussions about gender which you may or may not have, which is to disadvantage trans people. If they think they’re going to get votes by doing that, I think they’re sadly mistaken… I hope it’s too late now, that schools have reversed and follow the law and do not discriminate on the grounds of sexuality. That’s the law of the land. But I suppose that law could be tweaked, and that would be dreadful.”

Then comes the perfect dinner party anecdote: “I went to a talk at a school in Windsor. I thought it was a secondary school. I got there to see the students were between seven and 13. I thought, ‘I’ve nothing to say to these children!’ They had quite a lot to say to me! I said, ‘Will they be happy with me talking about being gay?’ It was a question the teacher had never considered before. ‘Why wouldn’t they be?’ Absolutely normal in that school. A boy came up to me and went, ‘You know my parents, David and Elton!’ If you’ve got Elton John’s son as a playmate, it’s not going to be a problem for you to know Elton lives with a man and not a woman!

“I think governments who are trying to put things in reverse will find it very difficult,” he concludes. “I think there would be revolutions in the streets, frankly.”

Here, in this edited, revised transcript of an hours-long interview, McKellen and Allam reflect on life, love, sex and the ageing process.

In what ways do you most and least relate to your characters?

Ian McKellen: My character is really opinionated. That’s nothing like me at all. [Laughs] I can play on that. He’s a contrarian. Likes upsetting people. I’ve noticed that with academics. They can get so absorbed in their subjects that they think they’ve mastered it, and nobody else can have a look in. I can relate to that. But then I found I could relate to Iago [from Othello], who’s a horrible person. Or Macbeth. Or Richard III. You can usually find some connection. Some moment where you’ve wanted someone out of the way.

Roger Allam: Or dead! Permanently out of the way.

McKellen: I don’t know about you, Roger, but you root around, don’t you? There’s never been a part I’ve played that I couldn’t find a connection with.

Allam: You find little things in yourself that you pull out and exaggerate to help you meet the character.

Are Frank and Percy the same age as you guys are in real life?

Allam: By curious chance, they kind of are.

I assume that adds an interesting dimension to the characterisation. If I was dating someone 10 years younger or older than me, there would be conversations about age gaps…

McKellen: When you get to mid-70s, mid-80s, there’s not much of a gap [anymore]. You’re both retired, you’ve both got prostate problems, you’re both widowed. They’ve an awful lot in common!

I recently interviewed Pedro Almodóvar—Allam: How wonderful!

Who told me, Ian, he’s always wanted to work with you.

McKellen: That’s very kind. Did you hear that, Roger?

Allam: I’m not remotely envious at all. I’m happy for you.

He has a film coming out soon called Strange Way of Life, about two men in their 40s and 50s reviving a love affair. His last film but one was about an ageing gay director. Do you think we’re malnourished for stories like these, like Frank and Percy, about older gay men?

McKellen: Probably we are. I can’t really think of one. I suppose you could make a case for Antonio in [Shakespeare’s] The Merchant of Venice being at least middle-aged.

Allam: There aren’t loads that are straight…

McKellen: The interesting thing is Frank and Percy was written by a 31-year-old.

Allam: He did say once that it was a way for him to pay homage to his grandparents. Not that they met when they were very old, but one strand of it is how they managed to stay together. The play explores the difficulty of forming a relationship and staying together — of being with, living with, having sex with someone else.

Is there any romance in your life, Ian?

McKellen: No, I don’t think there is. But like my 91-year-old friend who came to see this play, you’d hope, wouldn’t you? I have crushes on people. I wouldn’t call it falling in love. But I don’t want them to move in, thank you very much. I’ve got it all sorted, thank you. And I’ve got these nice gay friends who live just through the wall — I can see them anytime I want. I’m not looking for a domestic partner. I wouldn’t want word to go around.

Allam: There would be queues, darling!

McKellen: Do you think so? At my age — and actually at any age — you can get by without sex. A lot of people do.

Do you keep in touch with past lovers?

McKellen: There haven’t been that many of them. I made the mistake of breaking up with one and not seeing him for 20 years. Ridiculous. I tried to make up for it.

Allam: I’m friends with a lot of ex-lovers, ex-relationships.

McKellen: It’s all too easy to say: “We’re never going to see each other again. We’re out of each other’s lives, there won’t be any problems.” But there will be hurt. You start a relationship not knowing where it’s going to go — and then to stop it? You can change gear. I also think there’s a little bit of me that doesn’t want to have another relationship because I don’t want to be hurt. I don’t want to get married because they’ll want to get divorced one day. And I don’t think I can face it.

Allam: Whereas when you’re young, all those things don’t apply. You think, ‘I’m attracted to this person; I love this person… Oh, no, I don’t.’ Also, I love that line in the play you have about feeling ‘cornered’ by a relationship. Trapped, somehow.

McKellen: You think, ‘Oh, if only I could be on my own this evening, and not have to accommodate…’ Then when you’re on your own, you think [pretends to cry] ‘Where are they?! Everyone’s left me!’

Do either of you have advice for men struggling with the ageing process? I’m 37, and some of my friends describe not having kids and settling down as a ‘Peter Pan’ thing. Is that something you experienced?

McKellen: No. I thought 37 was rather a good age. You still look young, still have your energy. You haven’t started getting intonations of mortality. You’re probably doing rather well in your job. Everything’s before you. You’re nicely grounded.

Allam: In one sense, if you’re straight and lucky enough, as I have been, to have found a woman with whom you want to have children, that completely changes your life. Because even though we all fuck up so many times, there’s a powerful reason to be in it for the long term. Which is a very different thing. Not that there can’t be gay parents. But it’s a more difficult terrain to negotiate [if you’re childless].

Your public coming out story is very well documented, Ian, but are you able to share any insight into your personal one? At what age did you come out to yourself?

McKellen: I say what everyone else says: I don’t really remember. It’s always been there. There was no big revelation where I was attracted to another male for the first time. Before, I had been attracted to females — it was just a stage I was going through! I wish I’d been able to come out when I was your age. I’d have had a much better life. I remain angry and resentful that society put a lot of weight on my shoulders and other people’s.

Allam: What do you think of the generation, or certainly a lot of gay men who mourned the passing of secrecy?

I mourn that, because I think gay men were probably a lot nicer to each other because they looked out for each other. Now we’re all horrible to each other. There’s no brotherly code.

McKellen: Don’t let that make you think that it would be better if you were back in the closet. You couldn’t get a job at Attitude — there wouldn’t be an Attitude — and we wouldn’t be doing this play.

Allam: We might be.

McKellen: We might be, but we’d be having things thrown at us. I’ve heard that expressed, but I didn’t find it amusing one little bit. If you lived in Bolton [where McKellen spent his teenage years], which wasn’t even Manchester, where did you go as a teenager to find other gays? Well, you might queue up at the men’s loos. I saw no sign of gay life in Bolton whatsoever. Of course, it was there, but I didn’t see it. I thought, ‘That won’t do!’