Inside Queer Britain, the UK’s first dedicated LGBTQ museum

As period LGBTQ drama My Policeman arrives on Prime Video in the UK, historian Dr George Severs visits Queer Britain in London and reflects on the community's storied and often hidden history.

In partnership with Prime Video

A few years ago, during LGBTQ History Month, I went on a queer trail of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. I was armed with a map and a guide who could point out notable objects on display relating to our LGBTQ past. From homoerotic paintings and engravings to works produced by important figures from queer history, the tour was fuller than I expected. The items we viewed were remarkable but, outside of LGBTQ History Month, most of us would not have realised their significance. With the guidebook in hand, a beautiful bowl by Emmanuel Cooper could be seen as the artistic creation of a gay liberationist (Cooper was a major part of the Gay Liberation Front in London in the early 70s); without it, it was simply an elegant piece of pottery. The exhibits were queer, but the museum was not.

How wonderful, then – perhaps even liberating – to visit Queer Britain, the UK’s first museum dedicated solely to British LGBTQ history. Since it opened earlier this year in the fashionable Granary Square development behind King’s Cross station, 30,000 people have been through its doors, and with My Policeman, the heartfelt, Harry Styles-starring romantic drama exploring the very human repercussions of societal homophobia in the 1950s, now out on Prime Video in the UK, there’s no better time to connect with Britain’s queer history.

Greeting visitors as they enter is a specially commissioned photographic installation that proudly displays a gender-diverse and multi-ethnic queer celebration, making it clear that Queer Britain welcomes all. Contemporary, sleek and highly polished, the space is carefully curated, with cabinet displays on a number of themes. The current exhibition We Are Queer Britain seeks to tell the story of LGBTQ protest in modern British history. It does not relay a straightforwardly celebratory narrative; rather, political pamphlets and protest ephemera portray complicated, troubling moments from our past. Episodes of unbridled queer joy are interspersed with objects from the Aids crisis and items dating from the anti-Section 28 movement. The historical picture that results is a moving collage that successfully encompasses moments of darkness as well as light.

Part of Queer Britain’s magic are the stories its exhibits evoke. Unlike my experience in the Fitzwilliam, most objects here are ‘obviously’ queer. This often sparks joy in visitors as they recognise artefacts relating to their past. I visited with my colleague Dr Sean Brady, one of the leading experts on the British and Irish queer experience, and as we walked around the gallery, he regaled me with stories from his own queer history.

“I’m so old, I can remember Divine’s tour of Britain in 1984,” said Brady, pointing at the multicoloured dress worn by the legendary drag queen which sits proudly in the corner of the exhibition space. He then told me about going with his friends to see Divine perform in Liverpool that year. “We were caught up in a riot that was sparked in a club. Me and my friends had to flee while Divine fought off some very, very aggressive Liverpudlians who pulled off his wig – heterosexual Liverpool was not ready for Divine or his tour in 1984!”

All around the museum it was a similar story. Visitors would notice an exhibit and lean in for a closer look before nudging their companion next to them or summoning their friend from across the room. All around were whispers of “Remember that?”, “I was there!” and “Didn’t your friend go to that?”

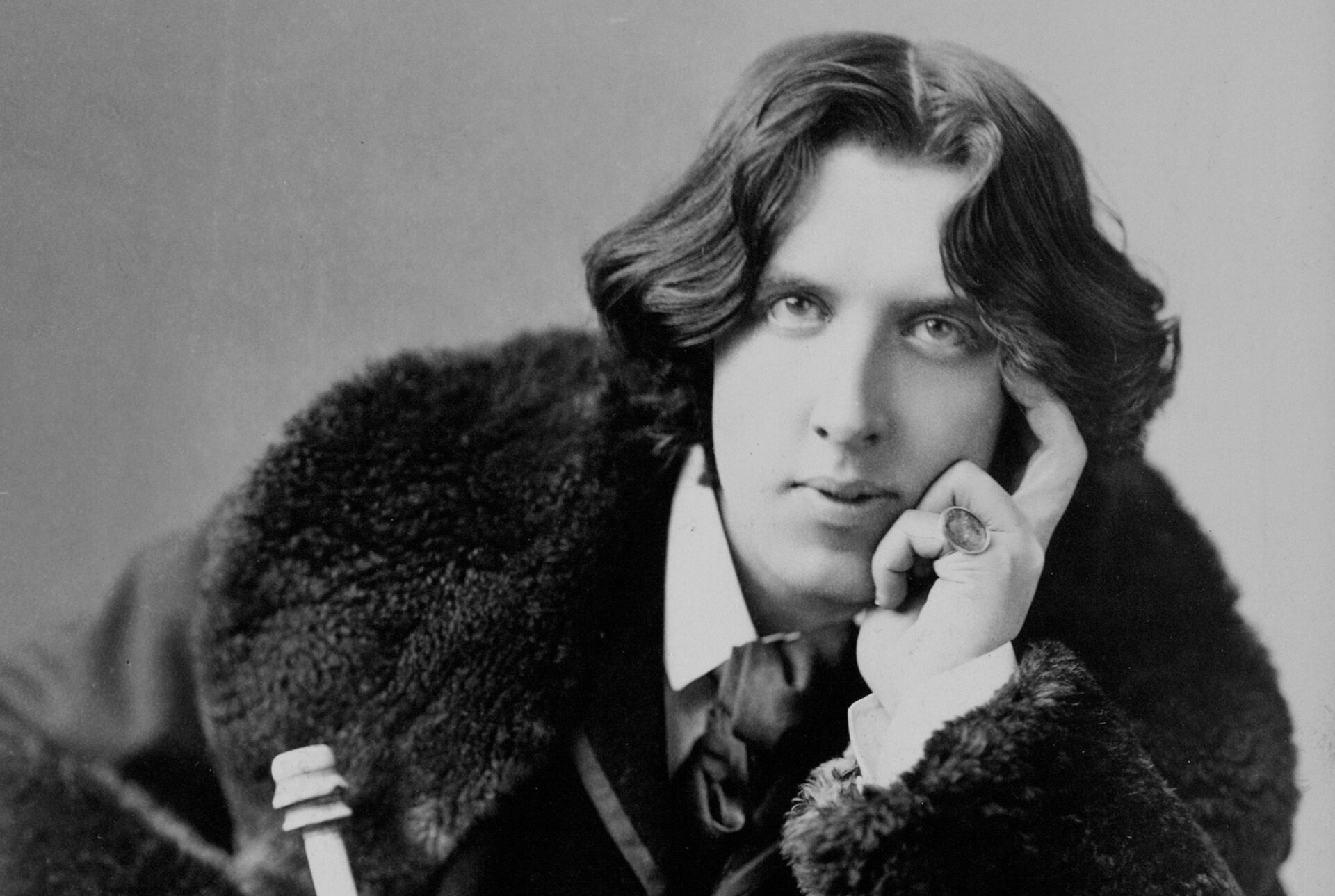

Perhaps the most historic (read: old) object currently on display is the door of Oscar Wilde’s prison cell.

Having been handed the harshest possible sentence (two years’ hard labour) for gross indecency in 1895, Wilde spent most of that time imprisoned in Reading Gaol. It was in his cell that he wrote De Profundis, a long letter to his lover Lord Alfred Douglas – aka Bosie – which has become a canonical piece of British queer literature. The door is a powerful exhibit. As an object illustrating the punishment inflicted on gay men in 19th-century Britain and a testament to some of the most powerful queer writing of its period, it speaks to the complex picture of British LGBTQ history.

“It’s actually more important than people realise,” said Brady of Queer Britain after we left. “Queer history has been a process of bringing into the light that which was hidden and invisible and obscured and very difficult to access or discern.” Having a physical, permanent museum is, therefore, a hugely significant development. The displays also had a profound personal effect on him: “I felt that this was an exhibition that marked my own life as an out gay man from the age of 18 in this country, and I’m now nearly 60,” he said.

Queer trails like the one I went on at the Fitzwilliam are important. They reclaim educational spaces that purport to be for everyone and show queer visitors that they have a place in a shared history. A dedicated queer museum performs a different task – one which is no less political. It legitimises queer history as an area of public interest. Here, our past is not hidden in a shadowy corner for curators to occasionally illuminate. Queer is unapologetically the focal point.

Queer Britain has been conscious to reflect a shared, inclusive queer past. How it will engage with moments of LGBTQ tension in future exhibitions will be a challenge, but the celebratory tone the museum has achieved is entirely appropriate.

“Society,” Oscar Wilde wrote at the end of De Profundis, “will have no place for me.” It’s a feeling most queer people will recognise, and one at which Queer Britain takes aim. It shows us that not only do we have a diverse, complicated history, but it’s one that has a legitimate, vital place in society.

My Policeman is available to watch now on Prime Video.

Dr George Severs is a Historian at Birkbeck, University of London