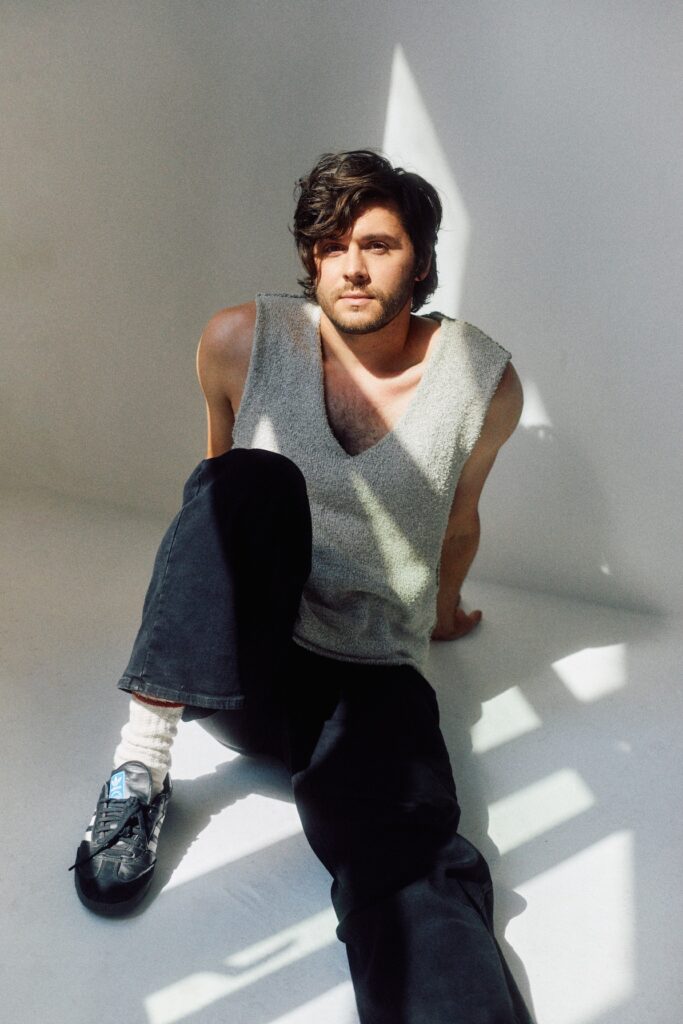

Lilies Not for Me’s Will Seefried on romantic gay drama’s depiction of so-called conversion therapy: ‘I dove deep’

Exclusive: "Society loves to pretend queerness is a recent phenomenon" says the filmmaker of his period drama exploring the scientifically-debunked practise of trying to change someone's sexuality

Based on real events, Lilies Not for Me presents a harrowing procedure aimed at curing homosexuality. What led you to choose this subject for your first film?

The idea for Lilies Not for Me started when I learned about a shocking procedure from the 1920s which claimed to “cure” homosexuality. This history struck me as a chilling expression of the violence that queer people still endure to this day, while evoking the books and films that were most influential to me as a young person — haunting period romances with queer relationships at their centre, like James Baldwin’s masterpiece Giovanni’s Room, Todd Haynes’s Carol, and Merchant Ivory’s Maurice (from the novel by E.M. Forster), to name a few.

I wanted to make my debut feature in this tradition. Society loves to pretend that queerness is a recent phenomenon, so I think there is great power in stories that explore the past in new ways.

Did you conduct extensive research on this procedure and the perception of homosexuality in Western countries during the 1920s?

Absolutely. I dove deep into sources like Curing Queers: Mental Patients & Their Nurses, which revealed fascinating accounts of friendships between gay men and their psychiatric nurses. Many nurses actually became radicalised, fighting the system from within. During this research, I learned about another often-overlooked aspect of this period – the presence of Black women working as nurses in the UK whose stories have largely gone untold. Owen and Dorothy’s friendship in the film grew from these parallel histories. On the medical side, I dug into old medical journals at the Royal Society of Medicine Library in London and even tracked down a 1920 documentary by Eugen Steinach about these procedures. A wild document of film history and Steinach’s work.

All that being said, I didn’t want the film to feel like a dry historical document. Our costume designer, Grace Snell, asked if the film was meant to be a painting or a photograph. That distinction wound up being imperative. Approaching Lilies like a painting — interpretive rather than dutiful — freed us to tell the story on our own terms.

How did the loving character of Owen come to fruition in your creative process?

Owen’s character grew from a place close to my heart. He’s a gay novelist in 1920s England who doesn’t see his sexuality as a problem. He just wants to love freely in a world that tells him he’s fundamentally flawed. As one of our producers beautifully put it after seeing the first cut, ‘That is Owen’s nature. To love.’ I’ll admit, I fell into that classic first-time filmmaker trap — Owen started out dangerously close to being me, down to his weakness for sweater vests. But then Fionn O’Shea came along and breathed life into Owen in ways I never imagined. Fionn’s portrayal gave Owen a profound capacity for love and a soft, almost feminine quality. The moment I heard him read for the part, Owen was transformed. The character started as a self-portrait, but Fionn’s performance turned him into someone entirely new.

The film features an exciting generation of actors and actresses. How did you prepare them for their roles and manage to make the alchemy work between them?

The alchemy between the actors was really organic. It all started with Rob, who I knew from his time at Juilliard. We spent over a year talking about the film and his character before we even started shooting. Rob was a huge champion for the project from day one. Funny story – Rob actually found Fionn for us while they were working on another project together. He called me, ecstatic, saying, ‘I found our Owen!’ Then, months later, on the very same day I decided to offer the Charles role to Louis Hofmann, Fionn randomly met Louis at a bar in London. So many insane moments of kismet.

We had similar luck with Erin, who I was absolutely set on within 30 seconds of meeting her, and Jodi, who’s been one of my closest friends for years and brings so much depth to every role she plays. My actual nephew played her baby son, and the film was produced by my husband Hannes Otto and our best friend Roelof Storm, so it really felt like we were putting together a family. This familial atmosphere extended to our preparation process too. We had some formal rehearsals — I’m a big believer in that, coming from theatre — but the informal bonding was even more important. For instance, Rob, Fionn, and Louis spent a weekend together at a cottage before we started filming, really diving into their characters and relationships. That kind of intimate groundwork was key to the whole project.

What led you to adopt this alternative writing and editing between past and present for the film?

The structure wasn’t really a calculated decision – it was more of a gut feeling. Looking back, I can see how Owen’s struggle with his past mirrors the film’s exploration of our collective history, but I’d be lying if I said that was intentional. The truth is, I was writing faster than I could think about the practical challenges of making a period drama as a first-time filmmaker. In post-production I had an incredible time with our editor, Julia Bloch, figuring out how we could maximize the back-and-forth between past and present.

There were many unexpected benefits to this structural conceit. Technically, it gave us another ‘world’ to cut to while building suspense. But more importantly, it let us showcase the stark differences in Owen’s relationships across these two timelines. The back-and-forth between past and present isn’t just a stylistic choice – it’s how we experience memory, how we grapple with our history. In the end, what started as instinct became a crucial part of our storytelling.

Can you explain the contrast you make between Dot and Philip regarding their relationships with Owen?

At its heart, ‘Lilies’ weaves together two pivotal relationships in Owen’s life. On one side, we have his longtime best friend Philip – it’s a forbidden romance, complicated by Philip’s determination to stamp out their mutual feelings. On the other, there’s Dot, a psychiatric nurse tasked with ‘curing’ Owen through a series of bizarre doctor-prescribed ‘dates’. The irony is, both Philip and Dot initially set out to change Owen. But as they grow closer to him, their paths diverge dramatically. Philip’s struggle with his feelings leads to a spiral of violence, while Dot’s journey takes her to a place of radical acceptance. The film is a conversation between these antithetical expressions of intimacy.

The film features a notable contrast between the warm candlelight within the house and the cold lighting of the hospital. How did you approach the lighting design for the film?

My cinematographer, Cory Fraiman-Lott, and I drew inspiration from a wide range of sources — paintings by Salman Toor, Henry Scott Tuke, Luke Edward Hall, and films ranging from Todd Haynes’ Swoon to PTA’s Phantom Thread to Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together. The list goes on. We went for a clinical feel in the ward but tried to subvert a predictable depiction of this kind of space with a grimy green-y texture, geometric compositions, precise camera movements, and wide lenses that swallow the characters.

The cottage, on the other hand, is all warmth and intimacy. But again, we wanted to challenge the typical saccharine look of a 1920s countryside romance. The camera functioned as an extension of the characters’ experience, rather than an outside form of surveillance, so compositions are messier and more subjective. Candlelight gave a sense of cosiness and nostalgia, but also a sense of things lurking in the shadows. As the story progresses, these opposing visual languages bleed into one another.

Lilies Not for Me will have its World Premiere in competition at Edinburgh International Film Festival on Friday 16 August.