Moffie: A play about the triumph of the human spirit over toxic masculinity

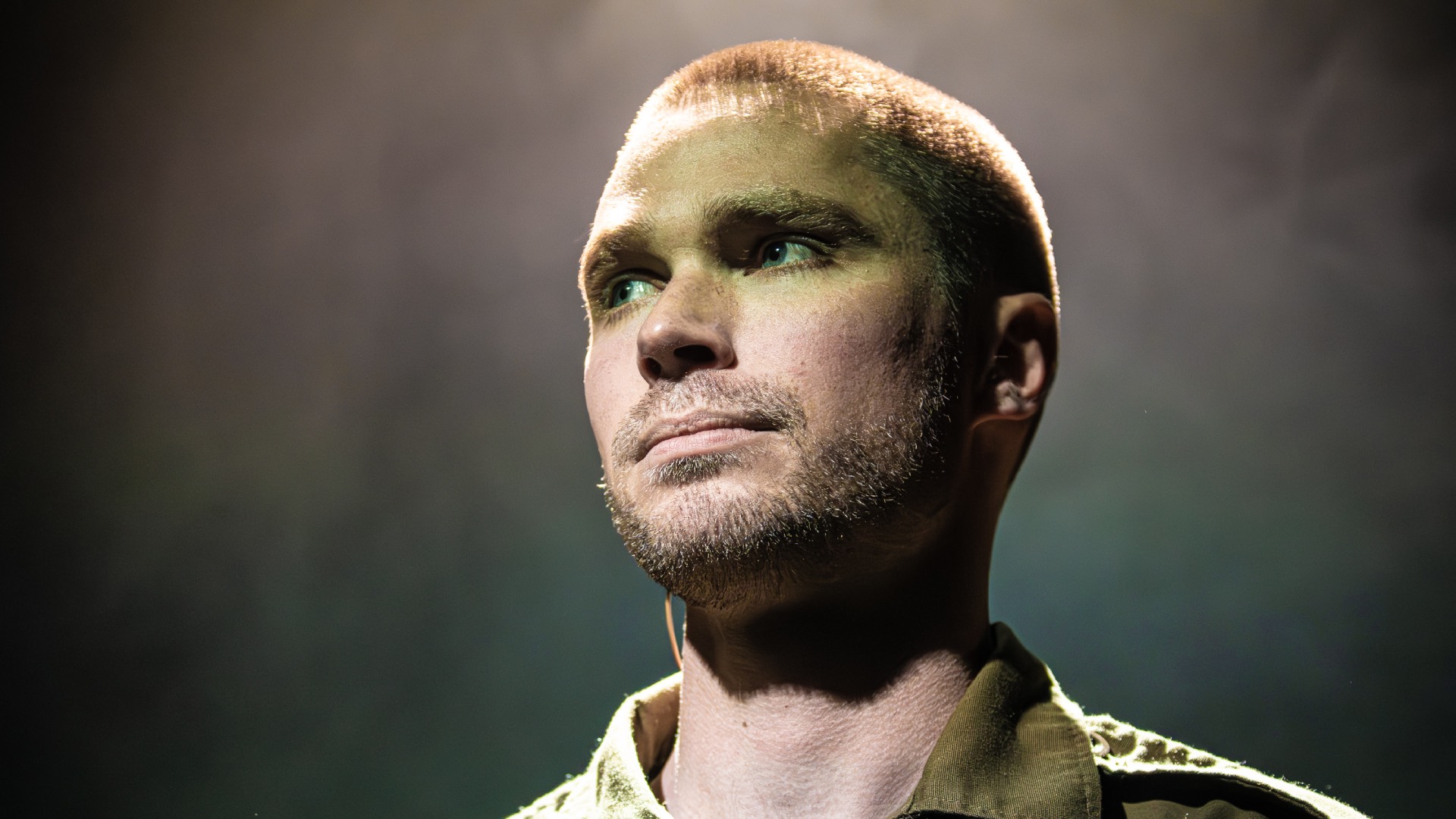

Adapted for the stage from the novel by André Carl van der Merwe, Kai Luke Brümmer returns to the role of Nicholas in Moffie, launching tonight at London's Riverside Studios

By Keith Bain

It’s been almost five years since South African actor Kai Luke Brümmer was hailed by critics at the 76th Venice Film Festival for his performance in the Oliver Hermanus film, Moffie. Based on the 2006 autobiographical novel by Cape Town-based André Carl van der Merwe, the film is a harrowing and beautiful and at times difficult-to-watchstory of gay sexual awakening in the context of his forced conscription into the South African Defence Force. There, as he does whatever he must to survive the brutality of basics training, he is witness to an onslaught of dehumanising atrocities, many of them aimed at anyone suspected of being homosexual.

Van der Merwe wrote the novel using the diaries he kept as a teenager and while in the army, having been conscripted in the late-1970s and sent to participate in the clandestine “border war” that was raging between South Africa and the so-called terrorists in Angola.

In the film, Brümmer gives a scintillating performance as Nicholas van der Swart, the film’s eponymous “moffie” – a slur, the equivalent of “faggot”, that was widely used in South Africa in the 70s and 80s, and to some extent endures today. Heartbreaking and visceral, the role made steep demands of Brümmer. Critics raved about his magnetic, quietly intelligent performance and the film drew resounding praise at the Venice International Film Festival, where it premiered in 2019 and garnered a six-minute standing ovation.

Now, at London’s Riverside Studios, Brümmer is reprising the role albeit in a completely different context: a one-man show that is charged with all the energy and fire and beautiful brilliance of the film and yet is even closer in spirit to the novel and, in Brümmer’s estimation, even more brutal.

It’s breathtakingly intimate, too, demanding a different sort of bravery from the 31-year-old actor who is an utterly absorbing presence as he conjures an entire universe of emotions through a succession of vignettes and memories that are woven together like a chronologically untethered fever dream.

Brümmer said that when London-based producer Eric Abraham (who also produced the movie) approached him with the idea of doing Moffie as a one-person play, he was initially “a little bit baffled as to how they would pull it off”.

The play, an exquisite adaptation of the novel by Cape Town author and playwright Philip Rademeyer, features Brümmer narrating the story as it twists and weaves and bounces back and forth between various moments in Nicholas’s young life.

It’s a hard ask, Brümmer essentially delivering an intensely energetic 85-minute monologue with no reprieve, not even a sip of water.

It makes “very different demands” compared with the film, Brümmer says. “In the movie it was kind of very internal and restrained.” By contrast, the play requires him to voice all sorts of bottled up feelings, give outward expression to his most private moments, his fears and his doubts. And to describe the source of his inner glow: a fellow recruit with whom he falls in love the instant he sets eyes on him.

Aside from the immediacy, and the extreme intimacy of having the audience right there, the play also requires him to switch roles, often in a heartbeat, as he briefly steps into cameos of other characters, be it a bigoted and quite terrifying army officer barking insults, or his homophobic, violent father. Not only does he whip in and out of quite contrary characters, but he breezes back and forth in time, one moment channelling a boyhood version of Nicholas, the next sweating it out as a bewildered soldier in Angola where he is confronted with scenes of ugly barbarity.

And, there are the scenes of purest poetry when Brümmer gives himself over to his character’s descriptions of how love and physical lust – those sensations of energy pulsing through his entire being – somehow manage to elevate him out of the despair and misery of the hate-filled army.

“It’s an incredibly tough play and it is emotionally taxing,” Brümmer says, although he’s no stranger to difficult and demanding stage roles. Before making Moffie the movie, he starred in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, about a 15-year-old boy with autism. And, in 2020, he turned in a triumphant performance in “Master Harold”…and the Boys, the Athol Fugard play which was Brümmer’s last stage performance before he moved to the UK just before Covid shuttered theatres.

“I’m a little older now,” Brümmer said of the time that’s passed since shooting the film. “We’re kind of outside the storyline of him being 17 years old and naïvely experiencing the world around him. Instead, like me, he’s older, has a little bit more perspective and is looking back.” Brümmer says in preparing for the play, he began from scratch. Did the research again, created his character from the ground up.

Brümmer says he believes the play has a great deal to say about the world we live in today, rather than being simply a kind of flashback to a dark time in South Africa’s history.

The play’s title alone is an act of activism, a kind of appropriation of the language of the oppressor. Each time the word “moffie” is used it opens a window onto a different kind of oppressiveness. Nicholas’s father uses it, army officers use it, fellow recruits use it to belittle, demean, feminise and emasculate. It’s part of the lexicon of bullies, a language used to subjugate, to traumatise. It is part of an inherited culture of toxic masculinity.

In the apartheid-era military context, “moffie” is also weaponised, a reminder to young soldiers that homosexuals are akin to communists, terrorists and liberals, all deemed enemies of the state.

In his brief to his team, Moffie director Greg Karvellas said he wanted the play to “feel like a nightmare”, in that it’s like a ceaseless onslaught of images and memory fragments. “It’s when you’re lying in bed and you’re thinking about the most embarrassing time, the scariest time, the happiest time… because memory works that way, it’s fragmented, it doesn’t always make sense, one thing leads into another. We jump around a lot because I wanted the feeling of a kind of fever dream. I wanted to feel like we’re in Nicholas’s memory palace.”

Karvellas, who for years was artistic director of Cape Town’s Fugard Theatre, now lives in Berlin. Moffie is his first international play.

While Moffie is about the particular agony of isolation and terror of being gay in a homophobic system, it is also about male inheritance, about where the values each generation of men inherits come from.

Karvellas says that, growing up, he – like most boys – was privy to a particular strain of toxic masculinity prevalent in South Africa. “‘Suffer, baby, suffer!’ That’s what my stepdad used to say to me all the time,” he says.

“White men in South Africa still say these things to their boys: ‘Don’t be soft!’, ‘Don’t be a moffie!’ And if you don’t fit into that mould, that expectation of how you’re meant to be as man, then you get completely lost. And, either way, you also carry that baggage with you, and so all that trauma just gets passed down the line.”

The play visualises this generational trauma with Niall Griffin’s deceptively simple set design: at the centre of the performance space, a pile of army-issue duffel bags which Karvellas refers to it as the “pile of trauma”, a metaphoric manifestation of what’s handed down father to son.

“These bags are the baggage, the collected trauma that you can never transcend, he says. “You just collect it all and it becomes the foundation upon which the next generation is built.”

At the same time, the duffel bags look like body bags, a visual metaphor for the consequences of war, essentially a machine for turning men into cadavers.

The other place where the trauma expressed in the play is felt physically, is in the soundscape created by Charl-Johan Lingenfelder who brings a rich three-dimensionality to the world in which Nicholas finds himself. While the soundtrack evokes environments and moods, it also in moments creates a deep sense of unease, of something deep-rooted simmering under the surface.

Moffie is not only a play about being gay in the military, nor is it only about a harrowing cultural condition that is uniquely South African. Rather, it is sharply universal and in fact feels incredibly pressing and prescient in this time when wars are flaring up and governments, for so long against conscription, are once again looking to institute the draft, calling young men like Nicholas to take up arms in conflicts that have nothing to do with them.

“Our artistic statement is that the men who are trying to mould us, trying to tell us to be something that we’re not, should not be able to touch us,” Karvellas says. “It’s about questioning, about not being sucked into the system, whatever system that might be. Instead, question everything: authority, social media, the status quo. This play is for thinking individuals trying to live in a free world and we believe that the way to achieve this is to constantly question the system.”

For Brümmer, who has now inhabited two versions of the same character, the play offers humanity as a form of protest against injustice. “More than anything else, what stands out for me in the play is hope,” he says. “As much as it’s very heavy and what this character goes through is incredibly tough, I think there is just so much love in it. I think it really captures this idea of hope as a form of resistance.”