12 images from Making a rukus! Black Queer Histories through Love and Resistance

We get the inside story on the new exhibit, running at London's Somerset House from 11 October 2024-19 January 2025

A powerful new exhibition called Making a rukus! Black Queer Histories through Love and Resistance is heading to Somerset House from 11 October. A staging of the work of the rukus! Federation – ‘an art project and living archive exploring contemporary Black LGBTQIA+ cultural and political history’ – the exhibition is curated by rukus! Federation co-founder and archivist extraordinaire, Topher Campbell.

Attitude recently caught up with the artist and filmmaker to hear more about the archive, comprised of over 2,300 pieces, spanning the 70s to the present day. “It’s about creating a playful, joyful, celebratory space for Black LGBTQI+ creativity and community,” he tells us.

“What we were conscious of, when we were young, was that if we didn’t do something to preserve the memories of our lives, nobody was going to do so,” Topher reflects of the collection, which touches on Black queer life in London, Birmingham, Manchester and beyond. “And people wouldn’t believe it. Thankfully, we had the energy to make this happen. So what you see is a vibrant, multi-dimensional culture, that even in the 90s wasn’t seen. It was so underground.”

“It’s not by accident – it’s through design”

Toper explains how the culture was “hidden because there was no social media, and also, there was racism and homophobia, particularly from the white gay scene, and white society, and also bigotry within the Black culture as well.

“You had all these ways Black queer people had to negotiate their lives quite strategically. But strangely enough, there were more Black LGBTQI+ pubs then than there are now, for men and women, and trans as well. So there you go!”

“The whole exhibition is an example of how culture gets hidden,” adds Topher. “Now, as we’re coming into newer times, there’s more of a space for it. But it’s not by accident – it’s through design.”

Here are some of the amazing stories behind just 12 images from the show – including one striking portrait of the interviewee himself.

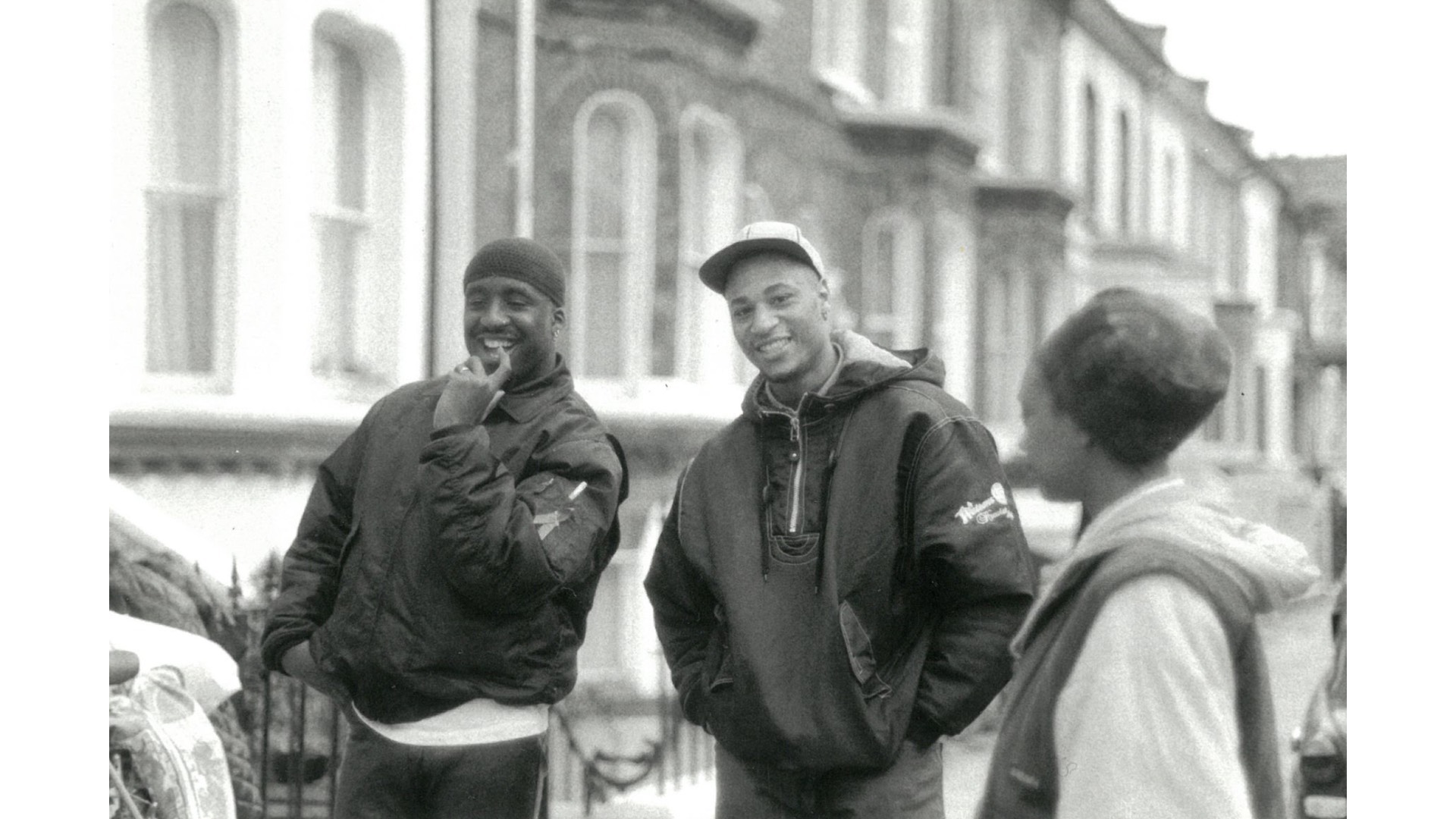

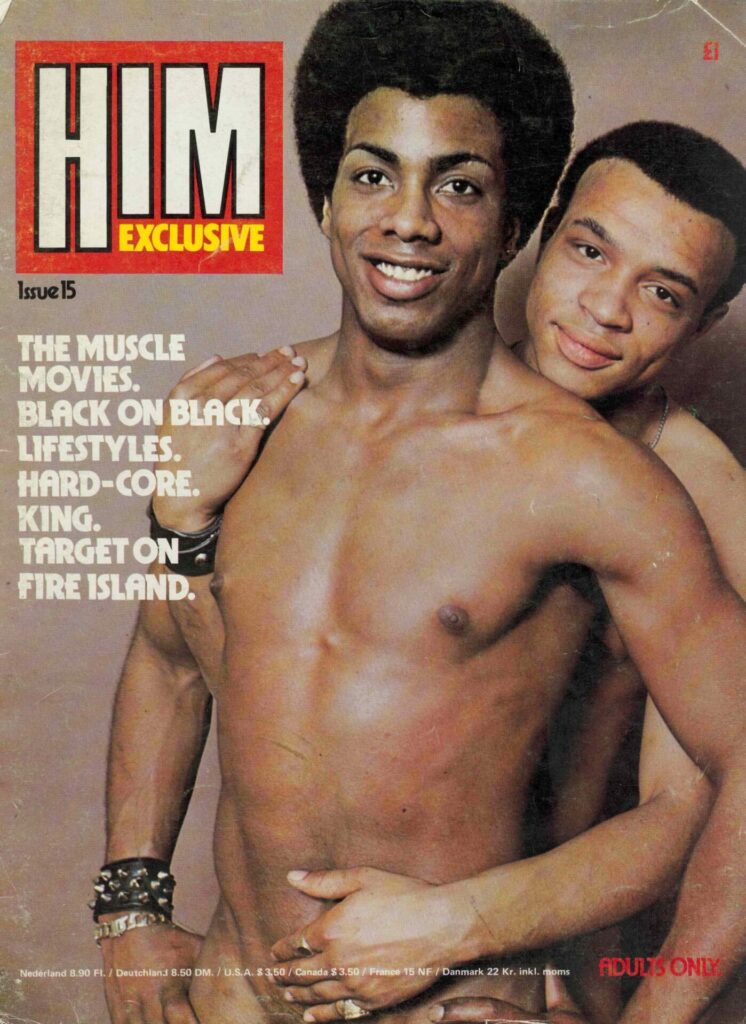

“This is a BTS of my first film, The Homecoming, shot on Railton Road, featuring Ajamu X, the photographer, who’s the subject of the film, and Terence Maynard, who is now well-known from Coronation Street. The film was about mid-90s Black LGBTQ life through the culture and perspective of Ajamu. It was the first time we worked together. It’s a beautiful picture, actually. I shot on Railton Road because, at the time, it was still resonant with the previous decade’s uprisings up in Brixton. So it was always seen as this no-go area. But that part of Railton Road is steeped in Black LGBTQI culture and history. I wanted to make a statement about filming on that street, to bring some of our culture and history into the foreground. This film is now at the BFI, as well as being in my show, and has become a bit of a minor classic because of that. I remember the day clearly, because two things happened. There was a show that used to be on called The Bill, and they filmed around Brixton a lot. There was a car chase being filmed down the street. Half an hour later, a real car chase happened! And there was a Rastafarian guy who was shouting at us from a second floor window. That we ‘shouldn’t be doing this nasty batty man thing on the street’. It caused a lot of interest.”

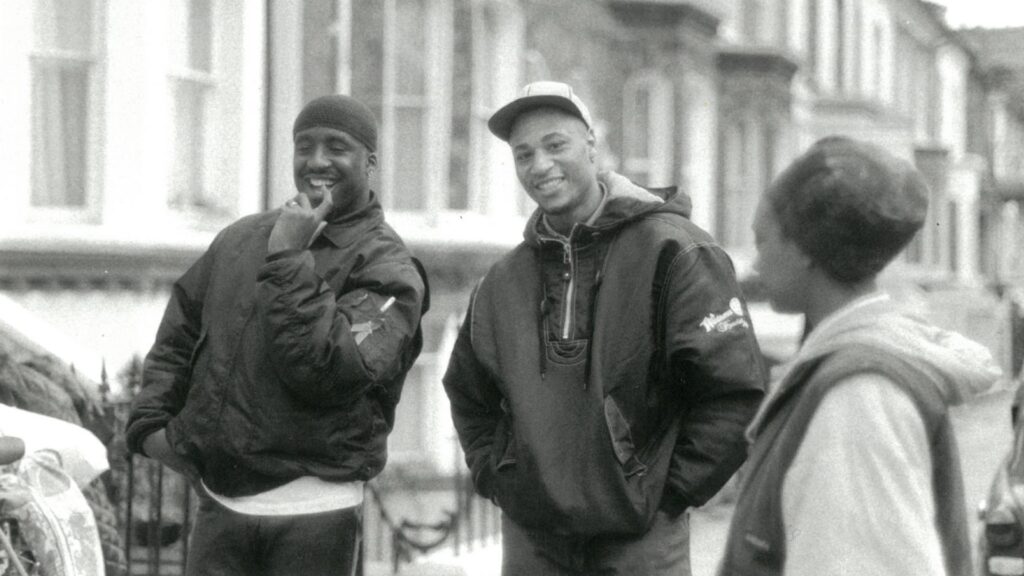

“This was the first Black gay men’s conference in Europe. There was obviously stuff happening in the US. Ajamu came to London to this conference. It was the first time he left his hometown of Huddersfield. I think it’s something that made him leave the North and come to live in London. I think this comes via his collection. I wasn’t there, it’s not part of my history, but it was the first time a gathering of Black gay men in the UK happened at that level. It may have been 200 people, maybe less. It’s a really important part of the archive. I made the film In This Our Lives The Reunion, of the 2007 Black gay men’s conference In This Our Lives – a reunion of various people who had been to that [1987] conference. It was a conversation they had, reminiscing, talking about the difference between now and then. It was an important film for Ajamu, and an important film for Black LGBTQI culture in the UK.”

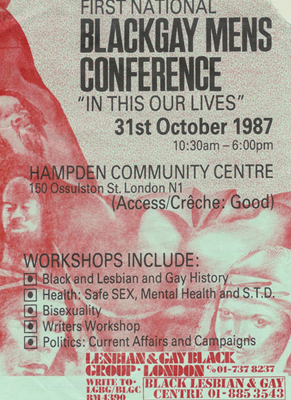

“Again, this is from Ajamu’s collection of porn; Black gay porn. It’s the ground zero of the rukus! archive. The reason is, we heard a rumour it was also shot by a Black photographer, but we’re not sure. All the times I saw porn, it was basically either a white [man] and a Black man, or it was a Black man being depicted for the white gaze. We were just intrigued by the existence of the cover of a soft porn magazine with a Black gay couple. And it came from a 1976 edition. We didn’t want to go beyond or before that, because we felt a lot of the image-making was by white people, whether gay, straight, male, female, we didn’t know. But a lot of things were more about the fetishisation; the voyeurism of Blackness. What we wanted to do with the archive was represent and showcase images by us, for us. Who are these guys? We don’t know. They could be in their 70s or 80s now, alive or not alive, we don’t know.”

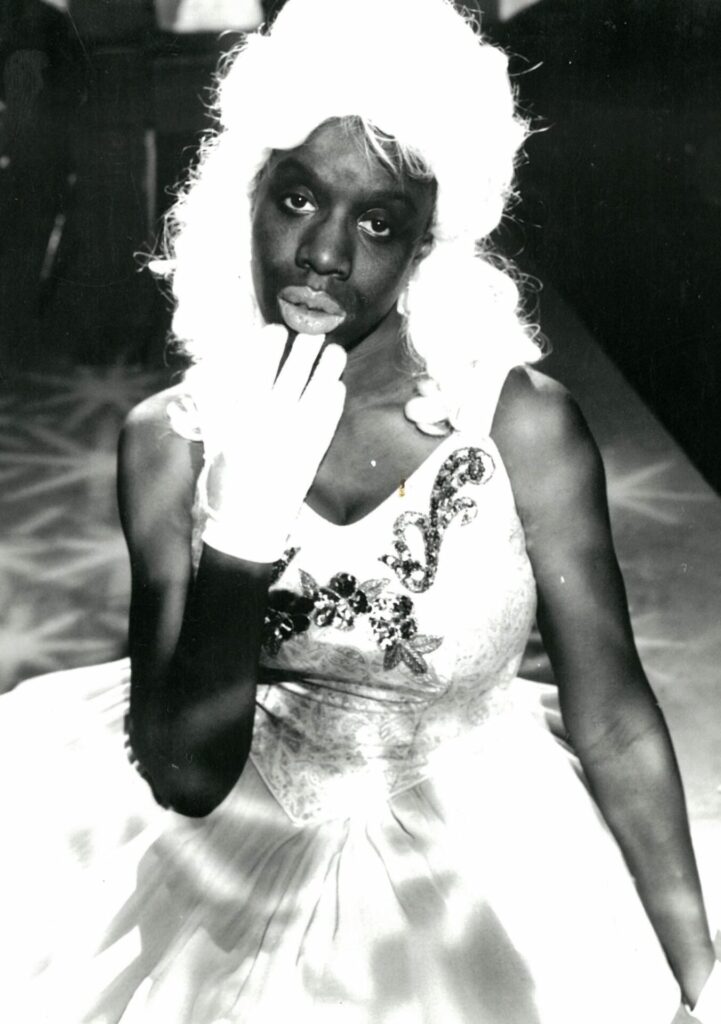

“This is Valerie Mason-John, also known as Queenie. She’s an inspiration. She’s like my older sister. She was a curator and the instigator of a lesbian beauty contest in the 90s. I was a go-go dancer at one of the clubs. This is from a play. It’s a publicity still. She’s a filmmaker, a theatre maker, an actress, a club promoter, an activist! She’s also a Buddhist teacher. She gave us £1,000 in 2000 to create an event at the ICA, which became the rukus! Federation.”

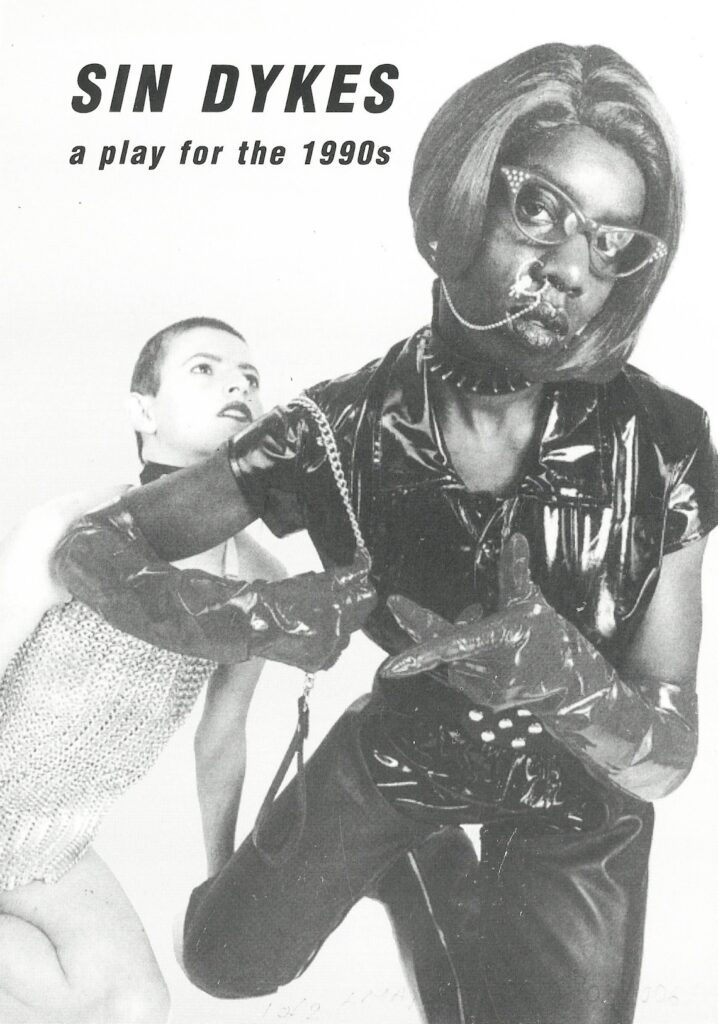

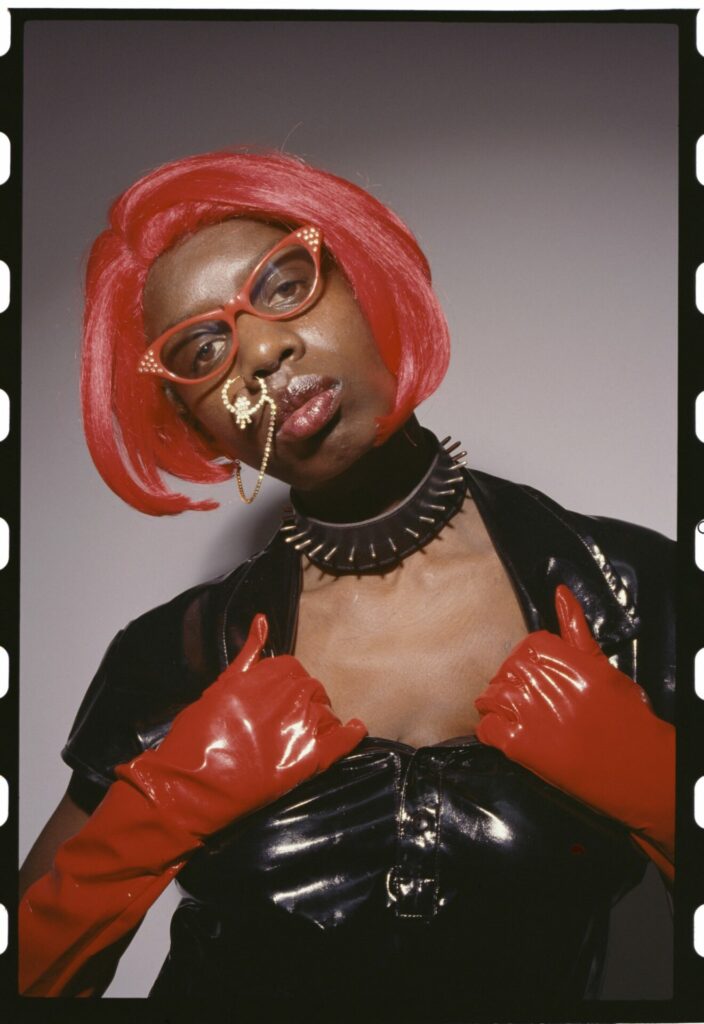

“This is Valerie’s play Sin Dykes, which looked at BDSM and interracial relationships. It was the first play for women, from a Black perspective, and it blew the lid off the theatre. As a youngster, I went to see it. I was starting to become a theatre director at that time. I thought it was the most mind-blowing thing. You had this strong Black woman doing exactly what you can see on the cover. Entering the stage with a white slave crawling behind her. This was 1997! The theatre was electric. There was a lot of call and response. We blow it up in the space that we’re in. And we use a lot of the publicity stills from her show for the exhibition itself.”

“Rotami Fani-Kayode is mentioned in [my film] – he lived in Railton Road. He is a seminal Black gay photographer, from Nigeria. He passed away in the early 90s through HIV and AIDS. This is a portrait called City Gent. The model is Ajamu. Ajamu knew more people than I did, because he’s a similar age to some of those people. But I got to know a lot of the Black LGBTQI Brixton and south London arts scene through Ajamu. A lot of what happened is, people would just appear in each other’s work. A burgeoning scene of photographers and filmmakers, including myself. Ajamu was living literally around the corner from Rotami, and became one Rotami’s models. It’s one of the famous prints that gets shown quite a lot, so it’s in the exhibition.”

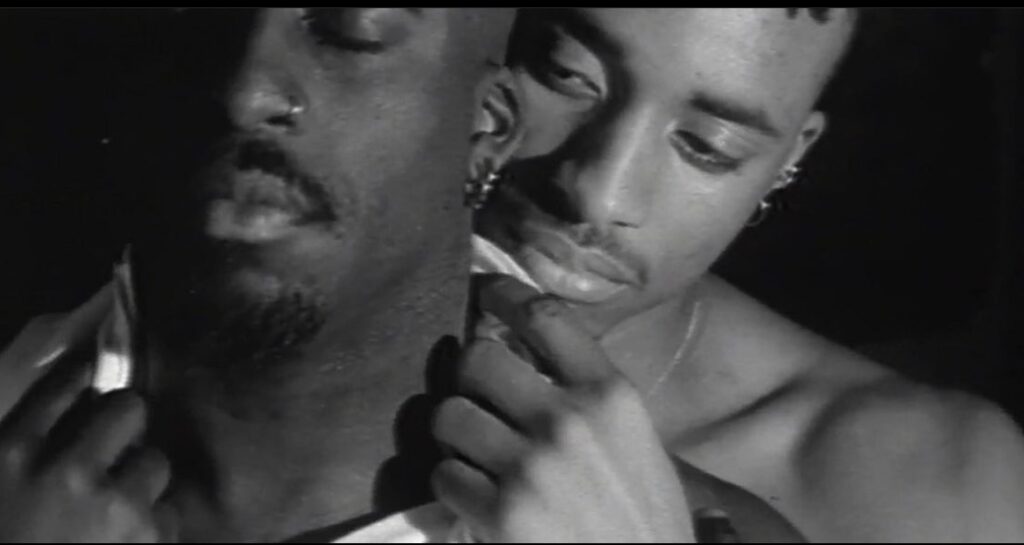

“That’s Ajamu on the left, and CJ, who was both a lover of mine, and also of Ajamu’s. He is in the film. This is me trying to give a representation of Black same-sex love, which just wasn’t seen. This is a scene from the film. The way I shot it was to mirror, in the same style of Ajamu’s photos. Intimate, tender, fetish items around hands and feet, and stuff Ajamu did that is not my aesthetic, but I was riffing off his. I shot it in monochrome. That’s a famous still that gets used.”

“This is interesting. In the late 90s, 00s, I used to go clubbing a lot. There used to be a drag and trans club in Freedom Bar in Wardour Street. The still is from the rukus! Federation launch at the ICA on the 23 June 2000. This person, I can’t remember their name, is someone I met at that trans bar. They’re French, and they were a ballerina. We got talking, having a laugh, I said I was doing this thing, and they said: ‘I’d love to come and perform at your event.’ They came, during Pride, performed, did this whole thing, upside down acrobatics! We gave them a basket of sweets to give out! I never met her again, and I don’t know where she is. But she was a joy.”

“Charlie Phillips is a famous, renowned fashion photographer from the 60s. I got commissioned to be shot by Charlie, and I chose to be shot by him on Railton Road. It was almost a poetic revisiting, if you like, of that space, for the very reason I shot the film. But this time, by a fashion photographer. He is an amazing guy, with amazing stories. We had a great day.”

“More stuff from Valerie! This is a publicity still. It’s probably not been seen before. It was on a lot of contact sheets in the archives and we produced it. So it becomes part of the iconography of the actual exhibition itself.”

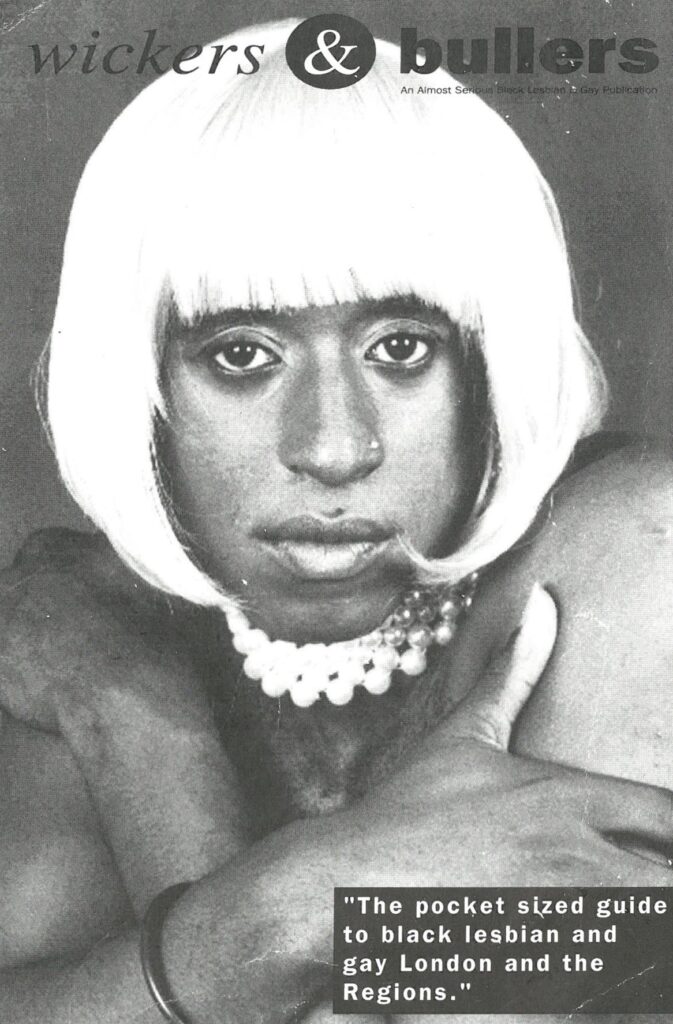

“There were quite a lot of Black LGBTQIA magazines. This was called Wickers and Bullers. It was the first commercially available [publication] – as in, you had to buy it; it wasn’t a freebie, like QX – produced for and by Black LGBTQIA people out of Brixton. This happens to be an image of Ajamu on one of the covers. Wickers and Bullers, MOC [Men of Colour] Magazine, In the Family – there were quite a few produced by Black LGBTQIA people, because we weren’t being seen in magazines. Our culture was always being seen as problematic. If there was a problem, the cameras were on us. If there wasn’t, no one was interested. This was a way of talking about our culture.”

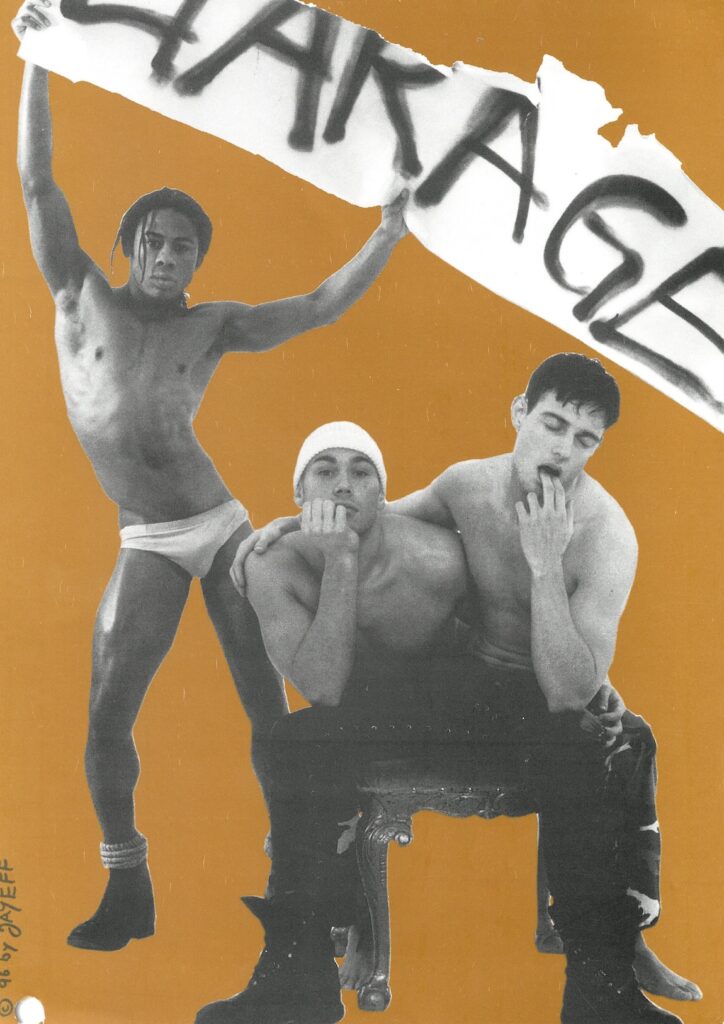

“This is quite a meaningful picture for me. The person on the left is Roger Dunkly. He’s an ex-lower of mine. Garage was a club night at Heaven. They were ‘it’ boys at the time, in the late 90s. Roger, bless him, passed away two years ago, unfortunately. It’s part of the whole club culture representation in the exhibition. Either spaces that we took up and created ourselves, or spaces that were already there, like Heaven. Roger was an out, proud, young gay man at the time. It’s also shows how the archive isn’t an abstract thing. It’s infused with my life, with Ajamu’s life.”