Equal age of consent: A comprehensive history of the battle for gay parity

20 years after parliament finally equalised the age of consent, Hugh Kaye looks back on the venomous, homophobic opposition to equality - and the activists who refused to be cowed by it.

By Will Stroude

This article first appeared in Attitude 329, December 2020

Words: Hugh Kaye

“Make sure your boyfriend’s at least 21 / So only your friends and your brothers get done / Lie to your workmates, lie to your folks / Put down the queens and tell anti-queer jokes / Gay Lib’s ridiculous, join their laughter ‘The buggers are legal now, what more are they after?’” – ‘Glad To Be Gay’, Tom Robinson Band, 1979

I first broke the law in 1973. I was 13, and had my first fumblings with another pupil at my all-boys school. He was some eight months older than me. Technically, we both could have gone to jail because the age of consent for gay men in England and Wales was 21, which had been set by the 1967 Sexual Offences Act. Scotland and Northern Ireland only came into line with this law in 1980 and 1982 respectively.

By the time my straight friends and I were 16, they could legally have sex – under the 1885 Criminal Law Amendment Act – and did. I still could not. Don’t tell anyone, but I might have transgressed more than once or twice.

An amendment to the 1885 legislation had ensured that any man found guilty of “gross indecency” with another man — even in private — faced up to two years in jail with hard labour. I suppose it was an improvement on the 1533 Buggery Act, which made convictions punishable by death.

Gay men faced the ultimate sanction right up until 1861, during the reign of Queen Victoria. As recently as 1991, 169 men who’d had sex with other men in England and Wales were convicted of having underage sex. Thirteen of them served jail sentences.

Securing equality over the age of consent would prove to be a tough battle.

The first chink of light appeared in 1957 with the Wolfenden Report. It recommended that ‘homosexual behaviour between consenting adults’ be decriminalised, with an age of consent of 21. But, fearing a public backlash, the Tory government under Harold Macmillan hesitated.

Nothing changed until 1966, when Labour MP Leo Abse’s Private Members’ Bill caught the changing mood in the country: a poll in the Daily Mail a year before had revealed that 63 per cent of readers who responded did not believe homosexuality should be a crime, although a stunning 93 per cent still thought gay men “needed medical or psychiatric treatment” (homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness in the UK right up until 1973).

Harold Wilson’s administration passed the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, making gay sex legal between two consenting men in private. I was seven years old at the time, so, not surprisingly, this passed me by — I’m afraid I was more interested in football and jumping off high things.

Then, in 1979, a Home Office group recommended lowering the age to 18 because that was the point when “society deems a young man to be an adult and responsible”. Again, nothing happened.

Now 19, I paid rather more attention to the legal wrangling this time. The gay scene was almost non-existent even in major towns and I remained an outlaw – albeit a closeted one. It was a case of “you can look, but you better not touch” – even if the object of my desires had wanted me to.

But Britain had joined what was then called the European Economic Community in 1973, and in April 1993 – the 98th anniversary of Oscar Wilde’s arrest in London – three men challenged the UK government at the European Court of Human Rights.

Hugo Greenhalgh, a 19-year-old student, and his 24-year-old boyfriend William Parry, argued that the law “created a climate of prejudice and fear”.

The third man, Ralph Wilde, 19, said: “The law is ridiculous. Why should we be treated differently from all our friends?”

There were, of course, opponents. A radio discussion in which Greenhalgh spoke of his relationship with Parry prompted a listener to demand the Director of Public Prosecutions bring criminal charges. The police asked for a tape of the programme and subsequently interviewed the two men.

There was, however, a more threatening shadow in the background: HIV/Aids.

Illustration: Gary Simons

Anthony Pinching, a professor of immunology at Barts Hospital, London, told MPs in 1994 that doctors were faced with a new epidemic of HIV infection because young gay men were not part of a “legal” community. “The fact that their sexual activity is illegal is a major constraint on the development of… safe sex,” he said.

Meanwhile, Dr Michael Forth, a consultant psychiatrist at Royal Liverpool University Hospital, said clinical work with students showed that many gays in their late teens were at risk of depression and learning difficulties through trying to conform with the law.

The go-ahead for the trio’s complaint in Strasbourg was given by the European Commission of Human Rights under articles eight and 14 of the Human Rights Convention, which guaranteed privacy and freedom from discrimination. All three had suffered homophobic attacks.

They were backed by Stonewall and a hearing looked likely to clash with an upcoming General Election. Pressure was growing on John Major’s government. Conservative MP Edwina Currie, calling the law indefensible and out of date, brought forward an amendment to a Bill to equalise the age of consent at 16.

Large numbers of Labour MPs, including then Shadow Home Secretary, Tony Blair, supported her. But there were those who opposed the move. Former chairman of the Scottish Conservatives, Bill Walker, said: “It is neither natural nor normal to carry out homosexual activity.”

Another Tory, Tony Marlow, said: “You are seeking to get us to vote to legalise the buggery of adolescent males. Do you really think that’s what our constituents sent us here to do?”

One of Stonewall’s founders, actor Ian McKellen, wrote: “We shall hear, once more, that boys mature later than girls and need the law to protect them from what may be only ‘a homosexual stage’. Medical opinion is almost unanimous that basic sexual orientation is fixed by the age of 16.

“Some fear that an equal age of consent would make 16- to 21-year-old men vulnerable to older men… The issue is whether 16 is too young an age for a man to consent.”

He continued: “The law says he is old enough to have sex with his girlfriend… Yet the law finds him less capable than, say, his twin sister, of resisting unwelcome advances. We will be told that young men should continue to be dissuaded from homosexuality because gay men lead such unhappy and unstable lives. Those of us at ease with our sexuality are neither unhappy nor unstable. Those gay men who have difficulty with their sexuality suffer greatly because of the discrimination they face [which] starts with the unequal age of consent.”

Elsewhere, the Bishop of Durham, the Rt Rev David Jenkins told Cambridge University students that justice demanded an equal age of consent and that homosexuals who chose to live in partnerships should be affirmed.

On the night of Monday 21 February 1994, during an emotional debate before the vote, Tony Blair said, “People are entitled to think that homosexuality is wrong,” he said, “but they are not entitled to use the criminal law to force that view upon others. A society that has learned racial and sexual equality can surely come to terms with equality of sexuality.”

You’d think victory was in sight. You’d be wrong, of course. The House of Commons voted by 307 to 280 against reducing the age of consent to 16, then voted 427 to 162 in favour of a compromise, setting the age at 18.

Prime Minister John Major and most of his Cabinet voted against the age of 16 but in favour of the compromise. The PM had not issued a Whip, leaving his MPs free to vote as they wished.

Those who voted against the lower age cited a belief that boys needed to be protected. Home Secretary (and future Conservative leader) Michael Howard, opting for 18, said: “We should not criminalise private actions freely entered into by consenting mature adults. On the other hand, we need to protect young men from activities which their lack of maturity might cause them to regret.”

Do me a favour…

Although I was now free to have sex, as long as my partners were also at least 18, the compromise — rightly — did little to mollify thousands of angry demonstrators who chanted slogans outside Parliament late into the night. At one point, several hundred protesters stormed an entrance, prompting the police to lock the gates. Three protesters were arrested.

Illustration: Gary Simons

Fortunately, activists and some MPs were not ready to give up. McKellen told the BBC: “In a couple of years, Europe will have told Parliament what it should do and Parliament will be forced to do what it failed to do.”

One young activist, Euan Sutherland, who manned the phones at Stonewall, said: “I feel insulted and disgusted by the vote. The Government, Parliament, are supporting homophobia, supporting prejudice and supporting victimisation of a minority group. In this country, a 10-year-old can be tried for rape or murder, but, as a 16-year-old, I cannot go to bed with a partner of my choosing.”

Elsewhere, a study at Sheffield Hallam University in 1997 analysed the arguments given for opposing equality, which boiled down to saying that the principles of right and wrong take precedent, the principles of democracy take precedent and the principles of care and protection take precedent. To put it mildly: BULL!

Those arguing against equality seemed to have conveniently forgotten the first article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) which states that “all human beings are born … equal in dignity and rights…” followed by the second article, which says: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this declaration, without distinction of any kind… race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, property, birth or other status.”

The university study concluded by saying: “It is important that we develop effective strategies to argue for lesbian and gay rights, by prioritising the notion of human rights; by highlighting that human rights are universal, inalienable, and indivisible; and by clearly illustrating how issues such as the age of consent are human rights issues.”

But it was to be the European Court that led the way again. McKellen was proved right and Euan Sutherland was the catalyst.

In summer 1994, following in the footsteps of Greenhalgh, Parry and Wilde, he, along with Christopher Morris, complained to the European Commission for Human Rights that the fixing of the minimum age for lawful homosexual activities at 18 violated his right to respect for private life under Article eight of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and breached Article 14 of the Convention, which prohibits discrimination.

Sutherland said that he had first had sex with another man at the age of 16 and although never prosecuted, there was a justified fear that he might have been.

In 1996, the Commission found that the existence of different age limits was discriminatory and that no valid grounds existed to justify that discrimination. They therefore found that the age of consent for homosexual acts should be lowered.

In response, in 1997, the UK government, now led by Tony Blair (with a Labour majority of 179), agreed to introduce a Bill to equalise the age of consent. The case in Strasbourg was suspended when Home Secretary Jack Straw promised to do everything possible to bring about a change in the law and thus prevent it proceeding to the European Court.

But opponents, including at least one hypocritical, very senior member of the clergy, were circling.

On 22 June 1998, Labour MP Ann Keen’s age of consent amendment to the Crime and Disorder Bill sailed through a free vote in the Commons with a majority of 207. However, the following month, the Lords threw it out, voting against by 290 to 122.

Amid bitter exchanges, the amendment’s opponents insisted that they were not antigay, but seeking to protect children.

Opening the debate in the Upper House, former Conservative minister Baroness Young said MPs had been “seriously flawed” to attempt to change the law: “It is clearly not wanted by the public, many of whom are quite fearful about what is happening to society. Homosexual practices carry great health risks to young people.”

Joining in on the attack, the Bishop of Winchester, the Rt Rev Michael Scott-Joynt said lowering the age of consent would undermine marriage and encourage people to indulge in a “sexual supermarket”.

Baroness Young later told the BBC that she was in favour of raising the age of consent for everyone. Lowering it could send “a sign that this sort of behaviour is perfectly normal”, she claimed.

Illustration: Gary Simons

Straw dropped the amendment, fearing that the government would lose the entire Bill, a major part of Labour’s legislative programme. He wrote to Keen, saying: “I understand that you will be disappointed, as am I, that we have not been able to secure the measure on equalisation on the age of consent in this Bill. I have no doubt that were I to invite the House to do so, it would send the provision back, with a large majority, to the Lords. But that would not serve any purpose.”

The government reintroduced the measure in January 1999, this time winning a majority of 183 in the Commons. But, despite an impassioned appeal by Home Office minister Lord Williams, who urged peers to put equality above the criminal law, the Lords – spurred on once more by Baroness Young rabbiting on about family values — again rejected it.

Stonewall’s Angela Mason said the defeat in the House of Lords was deeply disappointing. “It was clear [it] would always be close and in the week before the vote, sympathetic peers were reporting that Baroness Young was not confident of success.

“We believe the sudden shift was largely due to the public support she received from then Archbishop of Canterbury [George Carey, a long-time opponent of gay rights] and from the right-wing media.”

A statement from the House of Bishops had called on leaders to protect people from “harm and exploitation” and to offer them a “vision of what is good”. (Many years later, Carey would be heavily criticised, in a report by the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, for offering “overt support” to paedophile bishop Peter Ball.

However, there was a more measured response from The Bishop of Bath and Wells, the Rt Rev James Thompson. The law, he said, endorsed a judgmental and sometimes violent attitude towards homosexuality.

“It [makes] gays less safe and exposes them more to health risks,” he added. “It can create an atmosphere in which they are either encouraged to rebel, or more often to turn their fears into self-despising. To live a self-despising life is just about one of the most destructive things a human being can do.”

Liberal Democrat Earl Russell warned Baroness Young that the government would invoke the rarely used Parliament Act, allowing them to pass the Bill into law without the Lords’ consent. “I do not believe there are going to be any fewer homosexual acts if you are successful,” he told her.

Jack Straw said: “The issue raised in this Bill is one of equality, of seeking to create a society which is free from prejudice, where our relationships with others… are based upon respect and not upon fear. This Bill is long overdue for the statute book.”

Finally, and despite Ann Widdecombe, then Shadow Home Secretary, regurgitating the same old nonsense about protecting the young, and wittering on about political correctness, on 30 November 2000, after sailing through the Commons one more time and, predictably being blocked by the Lords, the government carried out its threat. A few hours later, the Bill received Royal Assent.

It didn’t make much difference to me by that stage, but it did to many young men. It was a vital piece of legislation, which finally came into effect in 2001. Although not every gay man gets married or adopts children, rather a lot of 16-year-olds want to have sex and not be branded criminals.

As we look back now, 20 years on, let’s leave the last word to Stonewall. Josh Bradlow, policy manager, said: “Securing an equal age of consent for gay and bi men was a long process accompanied by ugly debates grounded in harmful stereotypes.

“When the age for gay and bi men was finally lowered to 16 in 2001, it was a momentous and historic moment for equality.

“The passing of the law brought valuable recognition that gay and bi men should be treated as equals, not second-class citizens, and helped pave the way for many more legal victories on the road to LGBT equality.”

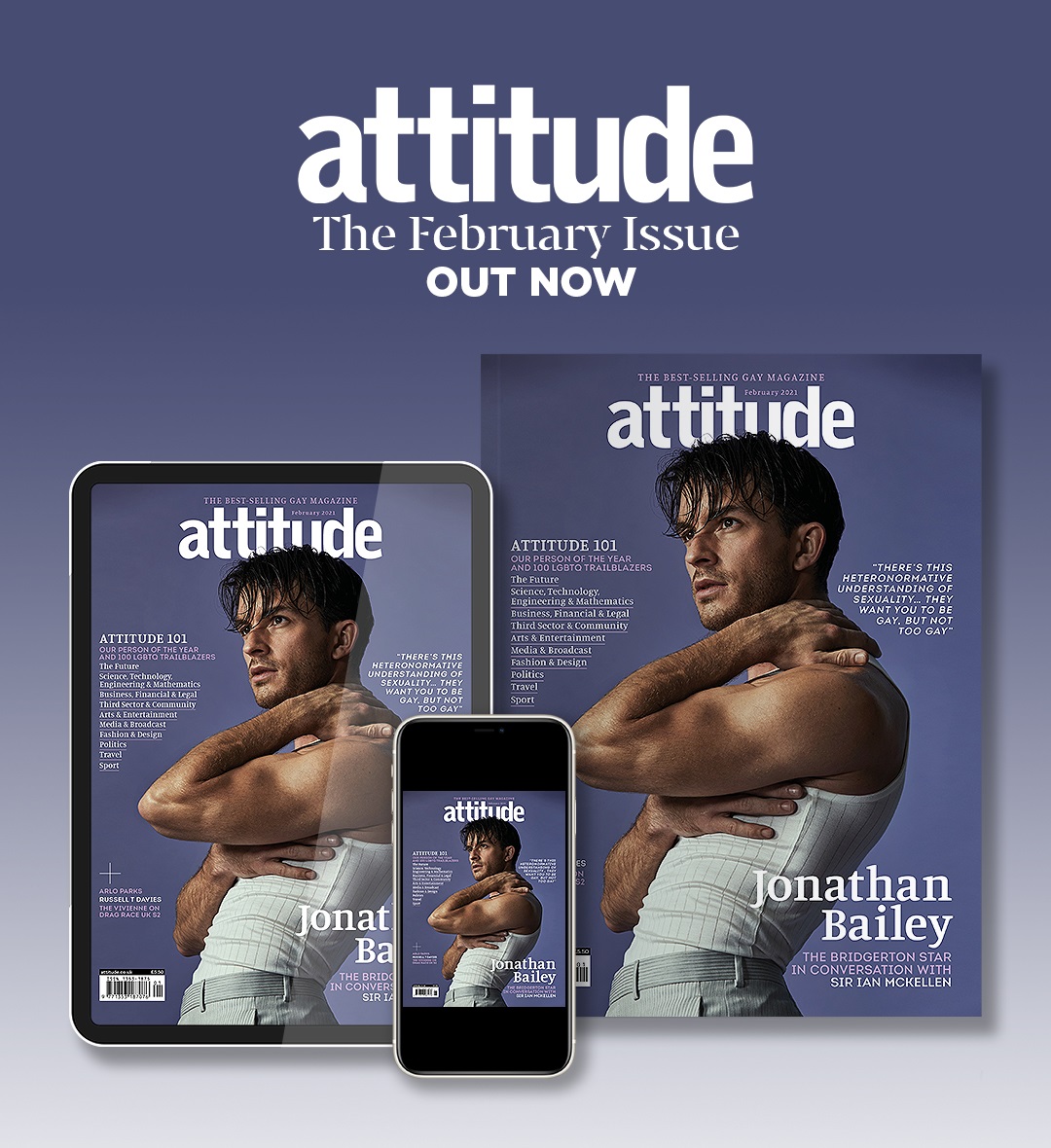

The Attitude 101 February issue is out now.

Subscribe in print and get your first three issues for just £3, or digitally for just over £1 per issue.