The former Gay Liberation Front member who’s spent 50 years fighting for LGBTQ rights

The protester is one of 10 everyday LGBTQ heroes honoured at the Attitude Pride Awards 2021, supported by Clifford Chance.

Interview: Cliff Joannou; pictures: Markus Bidaux

The Attitude Pride Awards, supported by Clifford Chance, are part of Attitude Pride at Home, in association with Klarna.

With a mother involved with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Black rights organisation that predated the US Civil Rights Movement, it was inevitable that activist Ted Brown would also devote his life to fighting prejudice.

The threat of violence was never far away. His mother and foster father were beaten up when holding hands after stepping off a Greyhound bus as they arrived in one of America’s southern states to take part in a demonstration. “My mother never obtained American citizenship,”

Ted, 71, recalls. “When the FBI accused her of being a troublemaker for being involved in the Civil Rights Movement, she was deported back to Jamaica.”

“I remember waking up in a sweat…”

The family eventually relocated to Britain in 1959, although Ted was on a more personal journey. “When I was about 12, I remember waking up in a sweat because I’d had a dream in which a friend and I were not very sexual, but more than just friends and romantic,” says Ted.

“I worried that this was an indication that I was going to turn into what we then called ‘sissy’ because the term ‘gay’ was only used by the gay community later on.”

Following the suicide of a friend who he suspected was gay, Ted, then aged 15, came out to his mother. She was sympathetic due to her awareness of Bayard Rustin, one of the organisers of the great Civil Rights March, at which Martin Luther King gave his ‘I Have A Dream’ speech.

“My mother actually had some logical, coherent arguments in support of gay rights, but I cried on her shoulder. She cried on my shoulder, because she said, quite rightly, that I would have to face both racism and society’s hostility to homosexual people.”

Life dealt Ted a cruel blow when his mother died a few months later following a severe asthma attack.

Watching the Civil Rights demonstrations on television, Ted realised the significance not only of heroes like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, but the actions of thousands of people facing the police, aware they would never be rewarded for what they were doing, yet had the courage to stand up for themselves.

“I did cartwheels all around the living room”

Further affirmation of Ted’s identity came when he read about the Stonewall uprising in a British newspaper. It reported on the 1969 event with an irreverent tone, saying how queens with their handbags were fighting the police in a bar in New York: “I did cartwheels all around the living room [on hearing] that there were gay people fighting back. But I had no way of contacting them.”

Then, in 1970, Ted stumbled upon a group protesting against the negative portrayal of gay men in the film adaptation of The Boys in the Band. They turned out to be members of the British branch of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). After joining them, he helped organise early marches through central London.

The first event, in 1971, took the form of a kiss-in in Hyde Park and Trafalgar Square to highlight how it was illegal for gay men to show any affection in public. “People think we were being flippant, but the sentence for that kind of behaviour could have been up to seven years in prison,” says Ted.

He worked briefly with Galop (the Gay and Lesbian Action on Police), which was set up as a liaison organisation for LGBT people who needed help from the police, but didn’t want to deal with them directly. “I suggested that we have a section for Black LGBT people as they had issues that didn’t apply to the white majority.

At the launch, the director of Galop recounted police comments about Black people. He quoted a police joke: ‘Why do white girls go out with n***** boys?’ The answer was to get their handbags back. I then left.” The annual report from Galop glossed over the incident.

Ted subsequently joined Lewisham Action on Policing, set up by the Black community to liaise with the police after the force failed to investigate an arson attack on a house in New Cross in 1981 that left 13 Black teenagers dead.

But it was Ted’s next move that would have far-reaching consequences for queer justice when he founded a new organisation, Black Lesbians and Gays Against Media Homophobia (BLGAMH).

One of the group’s early campaigns challenged the homophobia of the Black British tabloid, The Voice. After Justin Fashanu was discovered by The Sun newspaper to be gay, he was threatened with a very negative, explosive story outing him. Fashanu decided to come out.

“The Voice newspaper was strongly against him,” Ted says. “They ran a series of articles featuring Justin’s brother saying, ‘My brother is an outcast. It’s shameful that he’s gay.’”

The last straw for Ted and BLGAMH was in October 1990 when he says The Voice had “something like nine articles by various writers denigrating the gay community in one way or another”. BLGAMH targeted The Voice with a year-long campaign, winning a right of reply written by Ted.

The newspaper went on to change its stance, even featuring gay adverts.

BLGAMH also took on dancehall artist Buju Banton, whose breakthrough record ‘Boom Bye Bye’ featured lyrics calling for gay people to be shot with machine guns and burning tyres wrapped around their necks. “This was sung in Jamaican patois and was played on the BBC because the station didn’t understand the lyrics. A friend and I translated the lyrics and, of course, it was removed from the BBC’s playlist immediately,” Ted says.

“He and two of his friends came in and beat me up, knocked me out, stole money, property.”

Their protests didn’t stop there, and in 1992 Ted appeared on the popular Channel 4 programme The Word. “I went on to say that we gay people are not going to tolerate this kind of abuse any longer.” Ted adds that Banton later apologised for the lyrics, although the singer justified his actions, claiming that controversy sells records.

Ted’s activism placed him in physical danger when a group of men showed up on his doorstep. “What was particularly heartbreaking is that I had helped these people when I was working for Lewisham Action on Policing. I had helped a young man who was having problems with the police and was being wrongly charged with a crime. I had given him my phone number and address, telling him, ‘Please contact me if the police continue to ask for you.’

“After I appeared on The Word programme, he turned up at my house. I thought he was inquiring about his case. He and two of his friends came in and beat me up, knocked me out, stole money, property.”

Undeterred, Ted’s activism continued unwavering. Just last summer, alongside a reformed GLF, he staged a protest through London in commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the first Pride march in New York.

As Attitude celebrates the octogenarian’s remarkable life, Ted hopes his Pride Award is a symbol of the power each of us has to make positive change. He cites George Floyd as an example. “It was the action of that young woman keeping the camera on Derek Chauvin and George Floyd for nine minutes that led to the publicity and the outrage of the general population, and for once actually caused a police officer to be taken to account for the brutality that was being inflicted on the Black community.

“Individual action is extremely important. In the same way that prejudice and hostility is inflicted individual to individual and collectively turned into a serious social problem, so too action and support of human rights on an individual basis has an effect on society as a whole.”

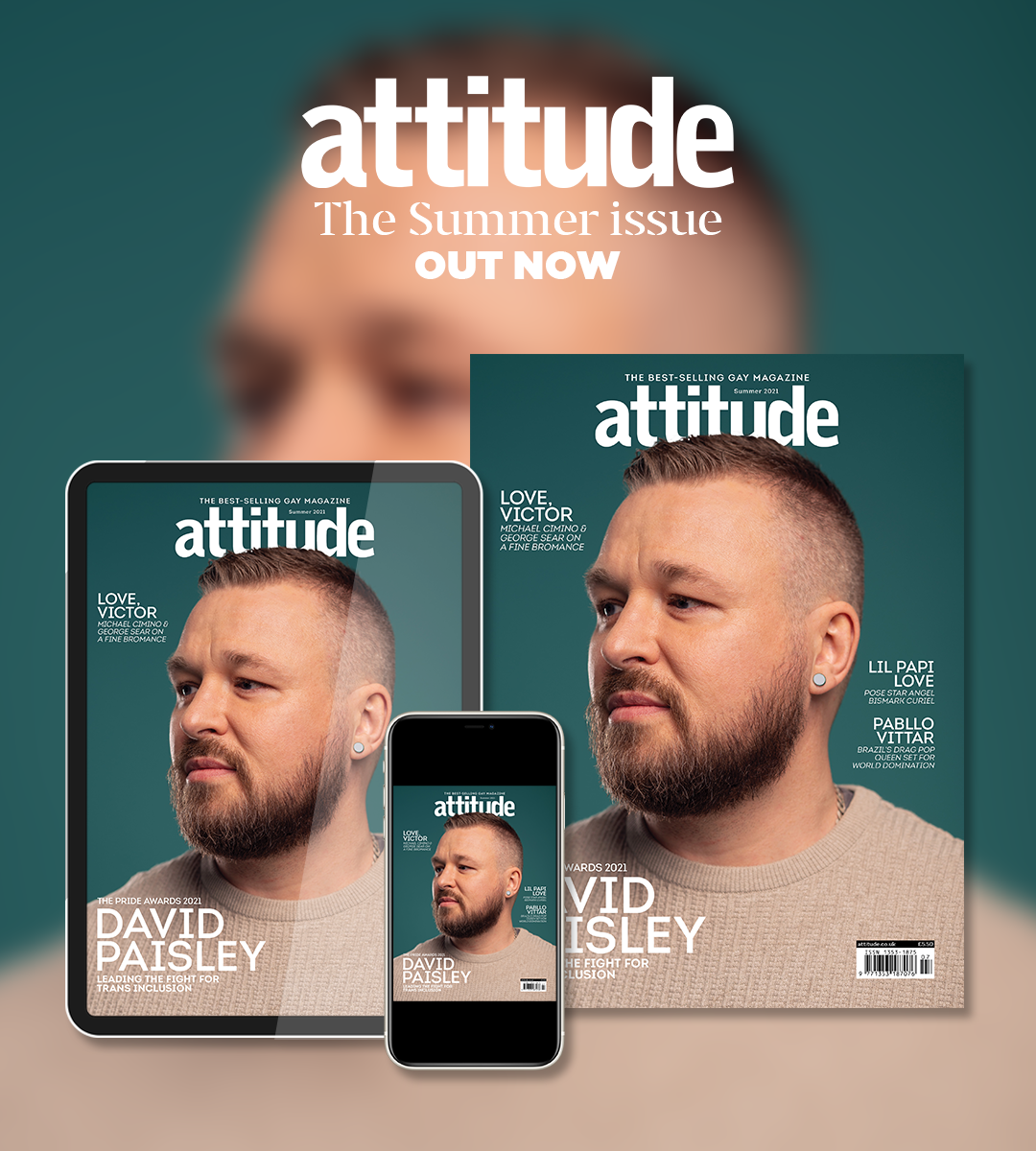

Read more about this year’s Pride Award recipients in the Attitude Summer issue, out now.

Subscribe in print and get your first three issues for just £1 each, or digitally for just over £1.50 per issue.