The woman who cared for more than a thousand dying gay men during the Aids crisis

Ruth Coker Burks' selfless work left her an outcast in '80s Arkansas - but the so-called 'Cemetary Angel' tells Attitude she doesn't want to be called a hero.

By Will Stroude

This article was first published in Attitude issue 315, November 2019

Words: Thomas Stichbury

Heroes come in many different shapes and sizes, and for more than a thousand dying gay man caught in the merciless clutches of the Aids epidemic in 1980s rural America, long-overdue help arrived in the form of Ruth Coker Burks.

A single mum from Hot Springs, Arkansas, she didn’t possess super-powers, or wear a cape that swishes in the wind. What she did have were huge reserves of dogged determination and, most essential of all, an endless supply of kindness.

Collecting her Attitude Hero Award [in 2019], Ruth briskly sweeps aside the notion that she is anything but ordinary.

“It makes me uncomfortable because I’m not a hero. I just did what everybody should have done, but didn’t,” she says.

That word “should” hangs over the Aids crisis like a spectre. Former US president Ronald Reagan, and his administration, ignored the fast-rising body count, dragging his feet and failing to act, wilfully letting struck-down members of the LGBTQ community waste away and die.

Some medical professionals also turned their backs, as did far too many members of the victims’ families, leaving them to suffer in the shadows.

Ruth, now 60, emerged as a beacon of hope in this darkest of hours.

Ruth Coker Burks pictured during the 1980s (Image: supplied)

Despite having no background in medicine, she ended up devoting her life to caring for those gripped by the condition, from something as seemingly small as giving a tender arm rub with an ungloved hand, to sourcing prescription drugs.

So, sorry Ruth, no argument. You are a hero.

In 1984, a 25-year-old Ruth encountered her first Aids patient while visiting a friend being treated for cancer at the University of Arkansas’ Medical Center. She noticed a door at the end of the hospital corridor wrapped in red plastic, with a group of nurses lingering outside drawing straws to determine, it turned out, who would have to go in.

“I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” Ruth says. “The young man’s food trays were lined up on the floor because no one would take them into him, and he was too weak to go out and get them for himself. I couldn’t take it any more, so I snuck into his room.”

That’s when she met twenty-something Jimmy. “Bless his heart, he was so frail. You couldn’t tell him from the bed, he was so thin. He probably weighed less than 75lbs.

“I took his hand and asked: ‘Is there anything I can do you for you?’ He said he wanted his mother and I thought, ‘Yay, I can do that, that’s something I can do’.

“I walked out and told the nurses, who were eating the cookies I had brought in, that Jimmy wanted to see his mother. They were like, ‘You didn’t go into his room, did you?’

“I replied, ‘Yeah, I did’, and they stopped eating the cookies. Then they said: ‘Honey, he’s been here for six weeks, his mama’s not coming. Nobody’s coming’.”

The nurses eventually passed on the phone number for Jimmy’s fire-and-brimstone mother, and Ruth endured a conversation she would hear time and time again, different versions, sure, but hitting the same depressing beats.

“I called her and she said, ‘I don’t have a son’, then hung up on me. I called her back and said, ‘If you hang up on me again, I will put your son’s obituary in the home-town newspaper and I will list his cause of death’.

“I knew I had her attention. She replied, ‘My son died years ago. I don’t know what that thing is you have up there, but it’s not my son’. I gathered myself and walked back into Jimmy’s room. I took his hand in mine and started rubbing his arm.

“He looked up and said, ‘Oh, mama, I knew you’d come’,” she continues. “I stayed with him for 13 hours until he took his last breath. I thought Jimmy was going to be my only patient, that that was it, I’d done my duty.”

Becoming an almost-accidental activist, Ruth juggled looking after her daughter, Allison, with caring for the sick, and, given the lack of information about Aids back then, you’d forgive her for being concerned about her own health and well-being.

However, Ruth insists she was never scared. “It wasn’t even called Grid [gay-related immune deficiency] yet. It was just ‘that gay disease’. I never wore gloves unless they had an open wound. I was never afraid of getting it. I remember asking a gay cousin about the disease and he said, ‘That’s just the leather gays in San Francisco’.”

Receiving referrals from hospitals in other cities, Ruth would ferry the men to their doctor’s appointments, arrange financial support and housing assistance, help them fill out death certificates, dumpster dive for food (“I didn’t have enough money to feed everybody, so I would take the food home, clean it real good and I’d make a big pot of soup or casseroles to take to them”) and at one point even ran an underground pharmacy.

“We didn’t have drugs for anybody, period, in rural America. I’d have all these boxes come through the mail with pills inside. People would send me the drugs they couldn’t take, or somebody had died [and didn’t need them any more]. I’d also go from person to person, house to house, ‘I need some AZT [the early antiretroviral medication given to Aids patients], can I borrow enough for three days from you and I’ll pay it back when we get it’.

Ruth pictured on Worlds Aids Day in 2017

“Is that not crazy?” she exclaims.

Armed with an enviable stockpile of sass, Ruth did not stand for ignorance or outright homophobia, most alarmingly from medics. “I’ve had doctors throw charts at me because I went into an Aids patient’s room with said chart. ‘Are you that stupid that you think you’re going to get infected from a chart? Are you having sex with that chart?’

“There was another doctor who told me he would never have an Aids patient in his office. I said: ‘Really? I find that very interesting since you have had three of them in, you just didn’t know they had Aids’.

“I was on the finance committee at church and I remember walking into a meeting and asking one of the doctors also on there if I could have a room to hold a support group meeting. He said, ‘Sure, but you’re not talking about bringing those people in here, are you?’

“I said: ‘Oh no, doctor, I’m not talking about bring those people into the church, I’m talking about walking those people across to your new $300,000 house we just bought, and I’m going to sit their asses on your $600,000 worth of furniture that we also just bought you,” she adds.

One young man who holds a particularly special place in Ruth’s heart is Billy, a drag performer she befriended in a local gay bar. “He was the most beautiful boy you have ever seen,” she says. “I was pretty sure he had Aids. He had ‘the look’. I took him to his first doctor’s appointment where he would officially find out.

“We drove by the zoo and there was somebody riding an elephant. He said, ‘I’ve always wanted to ride an elephant.’ I made a big U-turn in the middle of four lanes of traffic and said, ‘Well, Billy, you’re about to have your wish come true’. We got up on that elephant — I was in a dress with heels on,” she laughs.

Ruth Coker Burks with Billy (Image: supplied)

“He was a proud as proud could be. When we were coming back from that appointment, it was so quiet in the car. I asked Billy what was on his mind.

“He said: ‘I was thinking that when I die, I want you to have my Victor Costa dress.’ That was his prize possession.

“I said: ‘That’s so sweet but tell me the truth, do you really want me to have your red Victor, or you just don’t want your mother cleaning out your closet when you die?’ He replied, ‘A little bit of both’. I still have the gown. I can’t get into it now but it’s beautiful.”

As a parent herself, Ruth struggles to fathom how so many mothers could abandon their sons when they needed them most, and she shares the story of another drag queen, Rick, aka Miss Misty McCall, who “did Cher better than Cher does Cher.”

She adds: “Two of his friends were in the hospital room and they didn’t want to let me in. I told them that Norman Jones [the owner of a gay bar who ran fund-raising events for the cause and founded charity group Helping People With Aids, of which Ruth was executive director] sent me.

“I went over and took his hand, and they said: ‘He’s not going to know who you are, he hasn’t opened his eyes in a week.’ I called him by his drag name and he opened his eyes.

Miss Misty McCall, who became another of Ruth’s ‘patients’ (Image: supplied)

“He had so much edema [body-tissue fluid] in his legs, arms and hands that when he reached to hug me, he couldn’t. I kept calling his mother but she wouldn’t answer. Her answering machine picked up instead.

“I knew she was listening and I handed the phone [to Rick] and he was crying, choking and gagging, just begging her to come. She didn’t. She was only about two hours away,” Ruth sighs.

Sometimes referred to as the ‘Cemetery Angel’, Ruth buried a number of men in her family’s graveyard. “Throughout my childhood, my mother would say: ‘This is all going to be yours some day’. I was like, ‘What am I going to do with a cemetery?’

“Who’d have thought that I’d have a cemetery where I would be able to bury so many whose family didn’t want them.”

When asked how many of her friends are laid to rest there, Ruth pauses for thought. “There are 43 that I know of, but my daughter thinks there are way more than that,” she replies. “People would call and say: ‘My lover died and I have his ashes, can I put him in the cemetery?’ I’d go, ‘Sure, walk around and wherever you come upon a site that feels right, that’s yours.

Ruth’s family graveyard in Hot Springs, Arkansas became the final resting place for dozens of gay men (Image: supplied)

“One time, I had a young man and he had his partner’s ashes, his partner’s partner before’s ashes and somebody else’s.”

Often presented with remains in cold, sterile plastic bags, Ruth set about trying to find cheaper alternatives to an urn.

“I didn’t know what to do with Jimmy. I couldn’t bury him that way. There was no dignity in that. So, I went to Dryden Potter and enquired if they had any cookie jars that had chips in them that were discounted. I asked if they would donate them and they did. Who wouldn’t want to be buried in a cookie jar?”

After moving home to be nearer her grandchildren, Ruth isn’t as near the site as she used to be, and has since suffered a stroke. “It’s not a sad place. It’s a place that stirs up just love,” she says. “[But] I don’t go down there as often as I would like.”

Believing her encounter with Jimmy all those years ago was no accident – “I don’t think, I know that God put that room in my way so that I would go in” – Ruth has dedicated more than three decades to raising awareness as an activist, humanitarian and motivational speaker.

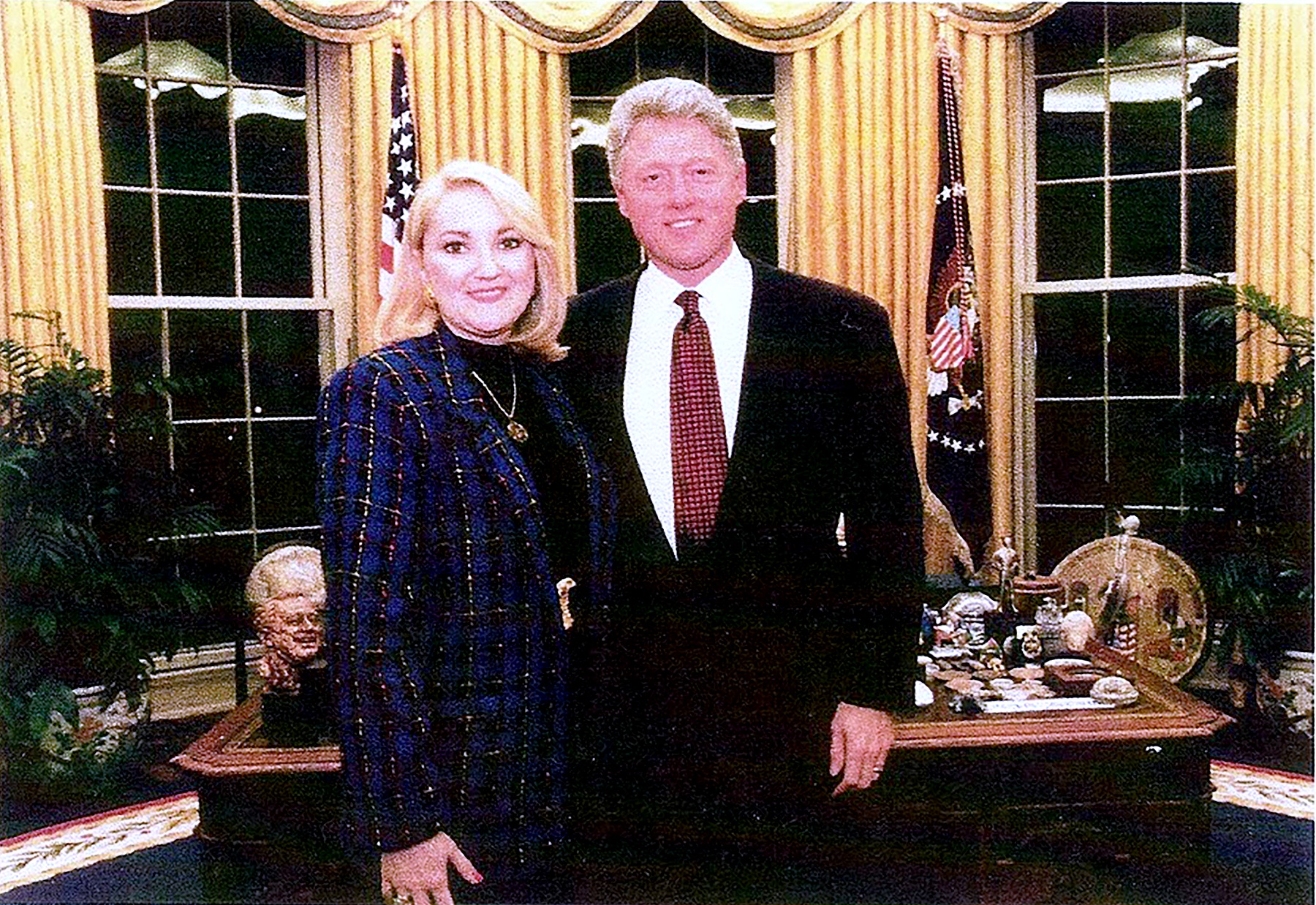

Notably, she was a childhood friend of former Arkansas governor and US president Bill Clinton, and went on to serve as a White House consultant on Aids education during his presidency.

“I would take these long, 15-page letters to Washington DC, up to his office, so he could read them.

Ruth with President Bill Clinton in the Oval Office (Image: supplied)

“If it had not been for Bill Clinton becoming president, I don’t think we would have stopped the Aids crisis,” she maintains.

Ruth moves on to Ronald Reagan’s term in office, specifically a 1982 briefing in which his acting press secretary Larry Speakes and a roomful of journalists laugh off the plight of Aids victims (a quick Google search brings up the chilling audio).

“Reagan didn’t mention Aids until I forget how many people were dead,” she says. “His press secretary once stood up in a conference and joked, ‘I don’t have Aids, do you?’ and everyone was just falling about laughing.

“[First Lady] Nancy Reagan asked Rock Hudson [a closeted Hollywood actor who died of an Aids-related illness] to come to all these fancy White House dinners,” she continues. “[Later], he called her many times when he was in Paris, because the American hospital there was the only one really doing anything for Aids patients, to help him get in.

“She never returned his calls,” Ruth says.

Ruth accepts the Hero Award at the Attitude Awards 2019 (Image: Kit Oates)

Back to the present day, and Donald Trump, who has been heavily criticised for his anti-LGBTQ appointments (hey, Pence) and policies, Ruth warns that the fight is far from over. “You’ve got to educate people,” she urges. “Then we need to take care of the long-term survivors. The stigma is what the problem is.”

Constantly required to reopen this chapter of her life and never being able to leave the book on the shelf must take its toll.

But despite bearing witness to so much pain, suffering and death, Ruth insists that an overwhelming feeling of love stems the tide of loss. “I loved every one of them,” she says. “If I didn’t love them for long, I loved them fiercely.”

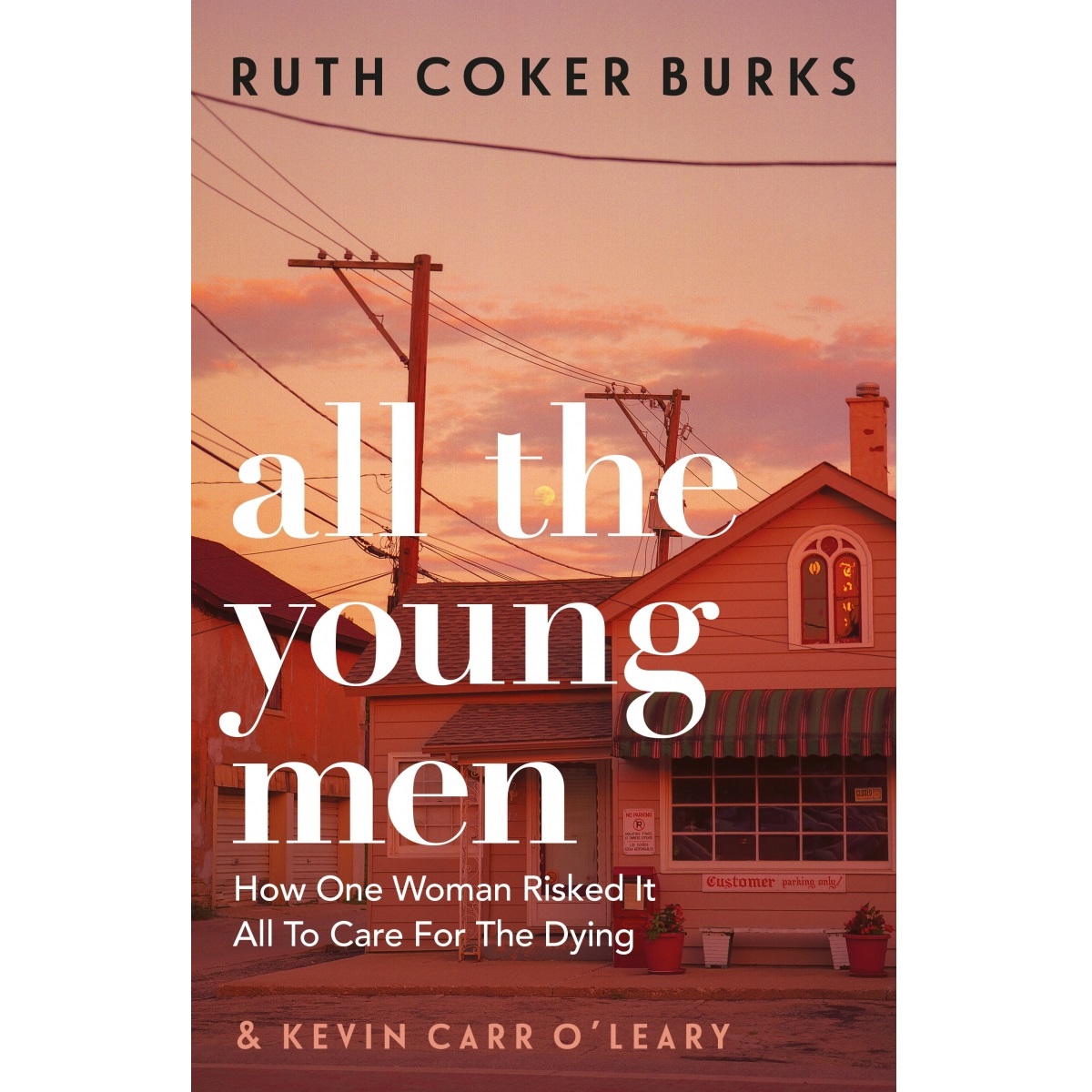

Ruth Coker Burks’ memoir, All the Young Men, is out now.