‘Watching is an act of activism’: Behind the Oscar-tipped film Welcome To Chechnya

Excl: "What's happening to queers in Chechnya hasn't happened since Hitler" director David France tells Attitude

Words: Jamie Tabberer; pictures: Provided

Would the international response to Chechnya’s anti-gay purge be different if it were straight, cisgendered people being targeted? A stupid question perhaps, and one with a resoundingly obvious answer.

But it’s something worth reflecting on daily, lest we become numb to reality.

“Oh, without question,” is the response of David France – director of critically acclaimed documentary Welcome to Chechnya – to the query.

“If it were a religious, political or racial minority, the world would have exploded in rage. But it’s a sexual minority.”

“What’s happening in Chechnya hasn’t happened since Hitler”

Drill down into the semantics, and the indifference gets ever scarier.

“Even under international conventions around genocide, it’s not possible, technically, to commit a genocide against queers,” says David. “Because we don’t fall into any of their defined categories of minorities that could be targeted for this kind of extermination.

“What’s happening in Chechnya hasn’t happened since Hitler – that queers have been identified and hunted, rounded up, tortured, and targeted for liquidation.

“The fact the world has not pulled together in a single voice to condemn that says too much about our political vulnerability on the world stage. Still.”

Given anti-gay Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov denies the purges are even happening (claiming in a 2017 interview: “We don’t have any gays. If there are any, take them to Canada”), France’s film breaks ground by offering stark insight into the situation.

We hear the stories of queer Chechen refugees, their faces disguised using cutting edge digital imaging. We witness, via hidden cameras, the heroic rescue attempts of Russian LGBT Network activists.

Such scenes are (sparingly) intercepted with archival/CCTV footage of the persecution in question – including torture and rape – making for a difficult watch that nevertheless jolts you awake.

Released last year, the documentary has reached millions via HBO Max and iPlayer. Now shortlisted for a 2021 Oscar, it’s set to reach millions more.

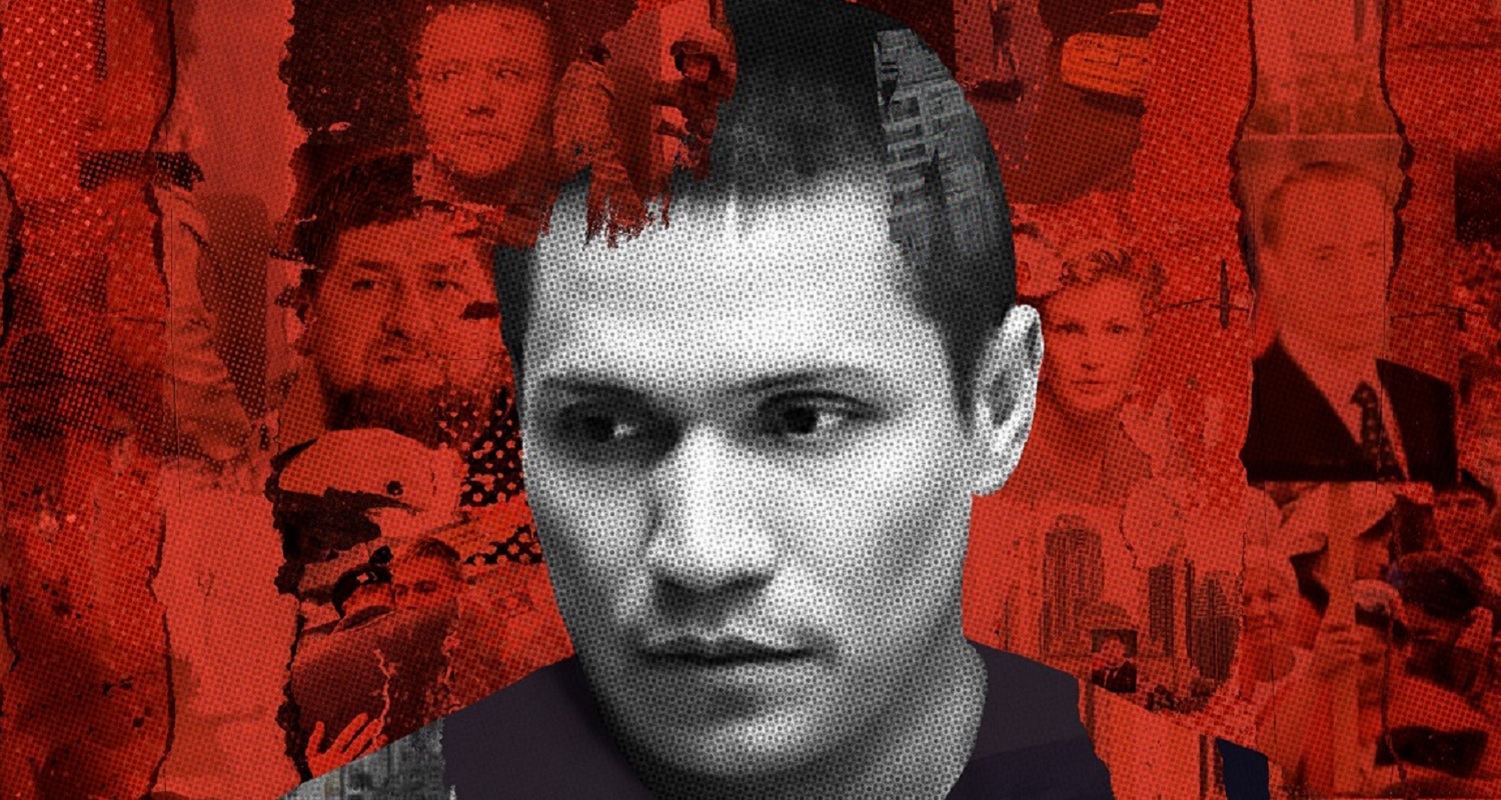

“A film like this, it’s hard to bring eyes to it,” admits David [pictured above]. “People think it’s going to be a tough film about a genocide. To get a nomination, or any traction in the awards world, tells people it’s more.

“That’s what a nomination did for [his previous documentary, on the HIV/Aids crisis] How to Survive a Plague. People kept telling me that I never should have put the word ‘plague’ in the title, because it scared people to death.

“Then, with an Oscar nomination, people went, well, what is this film? It lifted it up into this global orbit.”

WTC‘s new lease of life is timely: only last month, gay Chechan brothers Salekh Magomadov, 20, and Ismail Isteyev, 17 [pictured above], were kidnapped from their safehouse outside of Moscow and returned to Muslim-majority Chechnya, where they now face terrorism charges.

A Russian LGBT Network rep this week told Attitude how WTC has brought “a greater visibility of our activities and, of course, great support from the community.” On the flipside, financial support for the group is more important than ever as the film’s also increased “the number of requests for help from LGBTQs in Chechnya.” (The network has already helped 250 queers escape to date).

Here, David tells us more about the doc – and the other ways viewers can help those still trapped inside the southwestern Russian republic.

Are you still in touch with the people you interviewed?

Yes, with most on a very regular basis. We’ve been moving the film region to region, territory to territory – we have people hiding in those areas. So we reach out and let them know what’s happening. We talk to them about how they might be able to use the arrival of the film to their advantage. There’s a lot of coordination still going on for safety and security, as well as for engendering this political dialogue.

Was it difficult gaining the subjects’ trust and getting them to open up?

It was a process. When I first got into the shelter system, I had a standard appearance release. I realised this is no ordinary story. This release could not be standard. My team and I developed something we called the informed consent form. We promised we would revisit this idea of consent and release over and over through the process; that it would be continual. We would ultimately get their sign off only after we had finished working on their security concerns. That included the way their faces looked, and any other tell-tale sign that would pinpoint their identity to people who had some intimate knowledge of them, their lives, their possessions, the way they spoke, their body movements and the like.

Once we addressed all of that, then we got the sign off. That was almost a two-year process. So you can imagine what might have happened if we’d gotten down that road and somebody changed their mind, or wasn’t satisfied, or felt further endangered in some way. We may never have been able to release the film.

We recently spoke to the director of Netflix documentary Disclosure, and discussed funding and distribution struggles. How did your experience compare?

I had a different funding challenge. I couldn’t tell anybody what I was doing. For 18 months, I was sneaking in and out of a secret network. I couldn’t go to distributors and talk to them about it. I couldn’t go the traditional route of applying for grants through portals and submitting synopses. So we began by going person to person to major donors, to ask them to come on board in a big way. But also asking them to not reveal anything about what they were doing.

What is your advice be to someone who wants to support LGBTQ Chechens but feels at a loss as to how?

That’s such a good question. The first thing the Chechens in the film have asked for is to get their story out. To let the world know what happened to them, what’s happening to their queer sisters and brothers. Watching the film is an act of activism, as far as they’re concerned.

The other way is to help those activists on the ground. It’s not possible for them to receive funding inside of Russia, so they receive all their support outside. You can find out ways to do that on WelcomeToChechnya.com.

And as border crossings begin to open again, we can talk to our governments about being sure they know what’s happening in Russia, that they are opening up visa opportunities to the Russian LGBT Network, which is currently hiding people across Russia for months on end, as they’re trying to find partnerships with foreign governments to continue the pipeline to get them out of the country. If we can put pressure on our government officials to reach out to them, to empower a conversation, they might be able to relieve this bottleneck that COVID has created inside of Russia.

You’ve worked extensively as a journalist for the queer and mainstream media. Is it easier to say what you want in an article or a documentary?

It’s an interesting switch, because my voice is not in the documentary. It was a real leap for me to try to learn how to tell a story using this visual medium.

But what I fell in love with, and what I hadn’t had since I was working in the early days of the gay media, is collaboration and partnership. A team of people working together for the same goal. The last time that I loved work as much was when I was working for the New York Native from 1983-86, with really dedicated people whose knowledge was extreme and passion was undeterred. It gave me such a sense of mission.

“[On WTC] we pulled together a team largely of Russian exiles, almost all queer asylum seekers living in New York, and they joined on this project because of what it meant to them. I’ve learned so much from them. We cried so often in the process of making this film, not just looking at the footage, which is sometimes very difficult, but just talking to the people who are the subjects in the film, helping to calm them, reassure them. We became so embedded in their lives and journeys, and there’s a familial relationship that develops. I’ve learned to love the people who are in the film on a very personal basis, and certainly to admire their courage.

When you started your career in LGBTQ media, did you have hopes for what equality might look like four decades later? How do things measure up?

You know, when we were working in our queer trenches then, there were literally no examples of breakthrough cultural moments. There was a solid barrier between queer people and the rest of the world. There were no out gay journalists, actors, publishers. If you came out, you moved from culture into the ghetto.

So in my early days, we were an operation about bringing together the people in the ghetto and [starting] a conversation about what the future would look like. I can’t say we came up with any picture of that, because soon we were enmeshed in the HIV plague and that changed the conversation, and our immediate goal, to one of survival.

Welcome to Chechnya is available to watch on BBC iPlayer now.

Read the Attitude April Style issue, out now to download and to order globally.

Subscribe in print and get your first three issues for just £1 each, or digitally for just over £1.50 per issue.