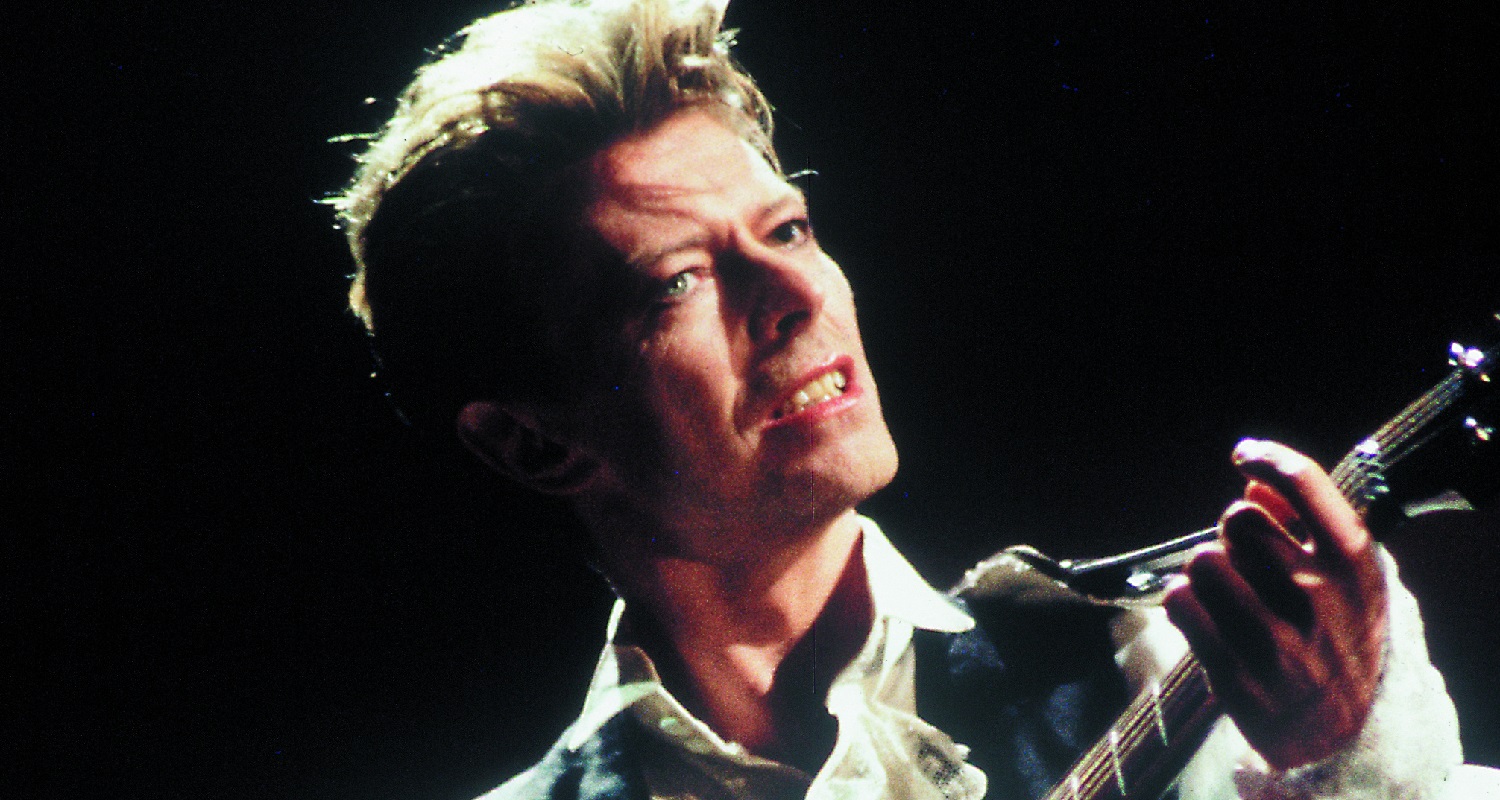

Why David Bowie was the godfather of modern queer culture

The rock icon died six years ago today (10 January) following a battle with cancer.

By Will Stroude

Words: Ben Kelly; Words: Wiki Commons

“Got your mother in a whirl/She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl.”

So sang David Bowie on his 1974 non-conformist anthem Rebel Rebel – a fitting place to begin looking at the queerness of Bowie, who brought the gay world to the masses at a time when it was still illicit, underground and edgy.

A quick trip through the early years of Bowie show a young man with infinite talents, but who struggled to catch a decent break.

The David Bowie Is… exhibition at the V&A in 2013 showed how he tried out various genre, disciplines and cultures to create something which could propel his vision forwards. By adopting queer themes, Bowie found what he was looking for.

His work between the breakthrough hit ‘Space Oddity’ and the stratospheric years of Ziggy Stardust were entrenched in camp. The LP cover for his 1971 album The Man Who Sold The World depicts the artist with long, Pre-Raphaelite hair, stretched across a chaise longue, wearing a full length dress.

Taking hippie to its utter extreme, Bowie was playing with gender long before we started throwing around phrases like fluid and non-binary.

Then, on the Hunky Dory album cover, he appears like screen siren Marlene Dietrich, with his hands placed on the sides of his painted face, his eyes gazing to the upper corner of the image.

The album screams of non-conformity, on tracks like Kooks, the iconic Life On Mars, and the tongue in cheek Queen Bitch, on which he comments: “She’s so swishy in her satin and tat…Oh God, I could do better than that.”

At this time, Bowie was married to his first wife Angie, with whom he had his son Zowie (nowadays known as Duncan). The pair had a very contemporary relationship that, depending on which biography you read, involved a colourful bohemian sex life; with Bowie often joking the pair had met while they were ‘fucking the same guy’.

She encouraged him to wear women’s clothing, and because homosexuality was still a curious taboo in British society (it had only been decriminalised in 1967), Bowie recognised that by hinting at queerness, he could not only explore something that was still very much underground, but he could also enhance his persona of otherness.

In a 1972 interview with Melody Maker, as he sat on the brink of Ziggy stardom, Bowie took a further step and announced, “I’m gay and always have been, even when I was David Jones,” – referring to his birth name, and the man behind the many masks.

He has since said he regrets making this comment, not just because it damaged him in the slightly more conservative America, but because ultimately, it wasn’t true. In a similar fashion to Madonna, Bowie merely borrowed homosexuality for his own provocative imagery, but crucially, neither did this entirely selfishly, with the result of their respective art doing much to enhance queer culture and visibility in the process.

When he emerged as Ziggy Stardust, Bowie became a symbol of all things queer. Performing as an alien from Mars “with God given ass”, Ziggy was androgynous, pansexual and slightly terrifying. When he performed ‘Starman’ on Top of the Pops on 5 July 1972, a nation of awkward teenagers – including future stars like Boy George and Marc Almond – sat transfixed by Ziggy.

It’s bizarre to imagine now that when he slung his arm around guitarist Mick Ronson, people viewed it as an explicit indicator of homosexuality. (Well, that and all the make up).

His ensuing 1972-3 UK tour became less of a musical concert, and more of a religious experience, with young misfits of all colours and creeds flocking to the altar of this starman who embodied their life on the margins of the mainstream. When he announced his retirement on the final night of the tour on 3 July 1973, it was received with screams and wails from devastated teenage fans.

He was, however, only killing off Ziggy, not his entire career. Throughout the rest of the 70s, as he took his new persona The Thin White Duke to Berlin, and went hard on cocaine and synthesisers, Bowie left behind the army of fans who had been so enthused by Ziggy, but he was to meet them again in the form of the New Romantics in ’80s London.

An entire generation of clubbers, artists and pop stars emerged in the late 70s and early ’80s with all the avant garde bombast of early Bowie, and many of them cited him as their main influence; from Boy George and Marilyn, to Spandaut Ballet and Steve Strange – the late host of the Blitz Club which was the mecca of the scene.

Legend has it Bowie visited the club one night before he released Scary Monsters and Super Creeps in 1980 and handpicked people – including Strange – to appear in his video for ‘Ashes To Ashes’. Once more, he took the queerness of a generation, and presented it to the masses, at the start of a decade which would be dominated by boys who looked like girls, and girls who looked like boys.

Again, this was not perceived to be Bowie stealing style, or jumping on the bandwagon: Bowie was a god to the New Romantics, and they worshipped him accordingly.

They say style is eternal, and for Bowie that was certainly true. He may have left behind his orange hair and red boots, but from McQueen coats, to moody black and white press shots, his effortless fashion has remained something many gay men admire, and hark back to.

His resurrection with The Next Day in 2013 also showed he still has what it takes to surprise, and that his creativity never left him. Released just a week before his death aged 69, the album Blackstar now reads as a profound sign-off.

The LGBT community are always paying tribute to Bowie, and from his songs to his clothes, to his far out concepts, and in many ways, he was the godfather of modern queer culture. As we mourn his unexpected passing, we can claim him as one of our own, with pride.