Zanele Muholi on photography and freedom: ‘There shouldn’t be any trans child leaving school because of laws’

Exclusive: To mark the launch of their self-titled show at Tate Modern, the South African visual activist speaks to Attitude about trauma, self-care and the importance of voting

“I just want people to have a new dialogue – the fact you’re asking me about it means you’ve noticed!” says a smiling Zanele Muholi of the four magnificent sculptures currently on display at their self-titled Tate Modern show in London.

The South African visual activist is of course best known for their photographs exploring Black queer identity, and over 260 are on display at Zanele Muholi: from soul-stirring, conversation-generating self-portraits to arrestingly honest and often painfully intimate shots of other people. But the unexpected stars of the show are decidedly 3D.

A monumental depiction of the artist’s genitalia (Ncinda, 2023.), for example, and another showing the artist tied up and sitting in a seemingly impossible position (Muholi IV, 2023.), creating a sense of physical discomfort in the viewer.

There’s work here about “undoing racism, speaking on crossing borders, on personal experience on being racially profiled, amongst many other things. A person could read that off the props used, if there’s a piece that speaks on being confined and arrested.”

“The sculpture piece where I’m sitting speaks also on the struggles we may face when we have voices we cannot express, and find themselves stuck in one position, unable to be let loose,” they add. “Whether abstract or not, there is something that draws us closer into sculptural pieces.”

“I want to expand my practise – there’s still a lot I wish to do” – Zanele Muholi

Excitingly, more mediums are to come, such as “quilting. Because quilting was a way in which our great, great ancestors told their stories. … I want to expand my practise. There’s still a lot I wish to do.”

But oh, those self-portraits, and the way they sear their way into your mind forever. One Muholi likes is “the picture where I’m wearing clothes pins, or pegs, to dry clothes and so on.” The picture (Bester I, Mayotte, 2015.) is “aimed at giving thanks to my mother … for all the struggles she’s been through to raise us. It speaks of women and work.”

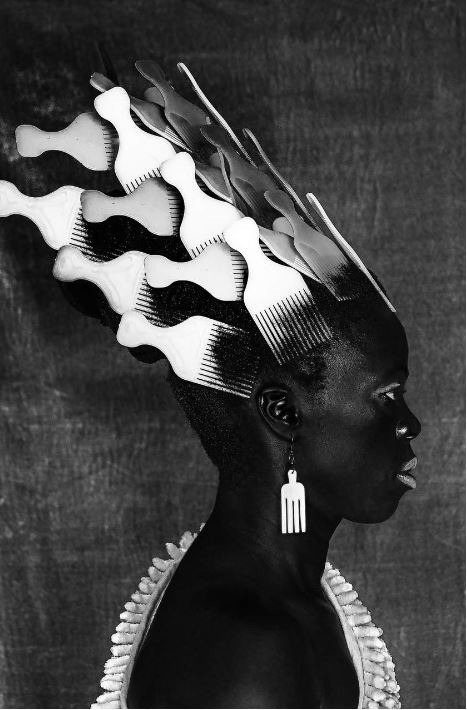

Qiniso, The Sails, Durban 2019

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

399 x 260 mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Here, Muholi reflects on why self-care is “political” – for example, of the South Africans they’ve photographed who are victims of violent sexual assault, or “corrective rape,” as male perpetrators call it, how many had tools of self-care available? – plus the international political pressure on gender expression and their hopes for the future of their country. Below is a transcript of our conversation, condensed for clarity.

I was curious to read about your beginnings as a reporter for Behind the Mask. Do you have any tips for me on how to conduct an interview?

[Laughs] It’s very important for the person to listen, and get the facts right, in order to write better stories. To know what I’m saying, to avoid distortion.

Do you consider yourself, as well as a visual activist and artist, a photojournalist?

It depends on the stories that we are documenting or capturing, and for which audience as well. To avoid … censorship that comes with the negatives in those stories. [It] speaks through the visuals. Activism speaks to the politic of how these visuals inform the public, or tells these stories. I’m an activist, right? So, my focus will be using the visuals as a political approach to it. It’s like that. Photography becomes another element in which we speak on what happened, in what corner. If you’ve seen the show, at the back, you have the activist room. That speaks perfectly to visual activism, where you leave alone the fine arts, but deal with topical issues, or things that are not often captured by maybe a person who is doing it through writing, or creative writing.

It struck me that you didn’t begin taking photographs until 32, is that correct?

My first exhibition was when I was 29. Besides that – I don’t come from a household that’s full of cameras and recording devices. I come from a poor background. My mum worked as a domestic worker. I’m raised by a single parent who had to raise children on their own. I don’t come from a space of abundance where you have all recordings and devices that make life easier.

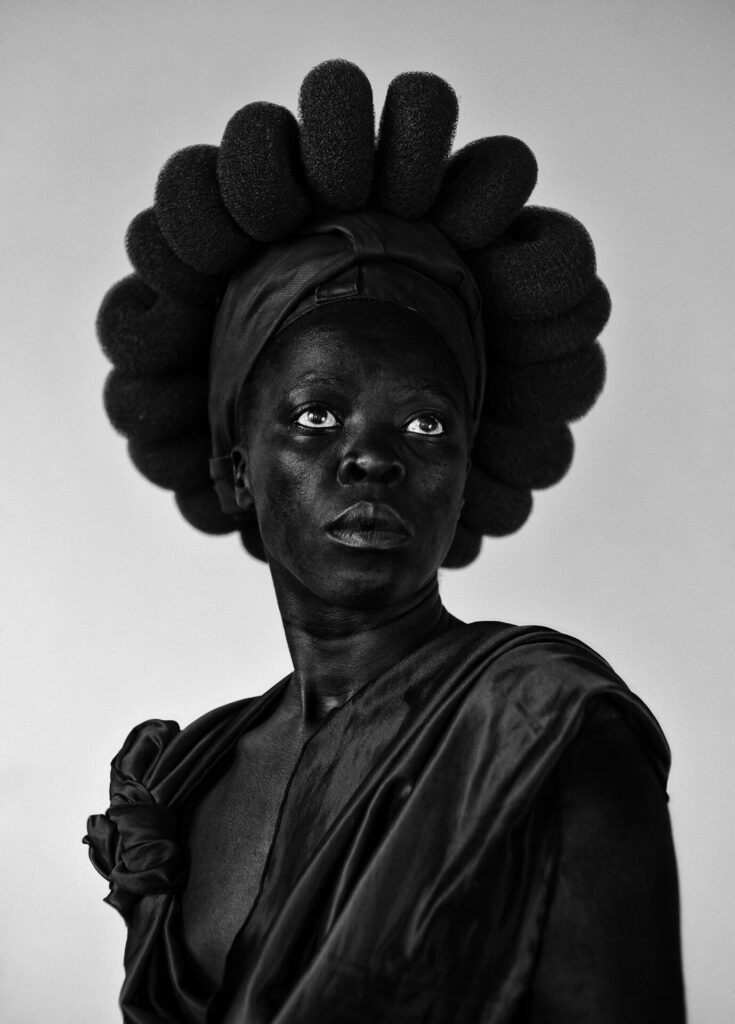

Ntozakhe II, Parktown 2016

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

1000 x 720 mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Did you have any creative pursuits growing up that informed the work you would go on to do?

Whatever I went on to do had to do with my queer self. Also, to speak on the lack of visual histories verses oral stories that we had access to as kids. Speaking on the visual history of South Africa, that lack – this does not mean it didn’t exist. But to say it lacked a visual that spoke to The Constitution of South Africa as it was changed in 1996. We had this very important document that speaks to protect the people – you need a visual that corresponds with it. Which should be presented in the most secure and mindful and meaningful way.

So, I just wanted to produce those images that spoke about the pride we have in this constitution. Also, to speak of the presence, the existence of the people as well. When you go to Pride, most of us go for a meaning. To push a political agenda that is not often asserted bluntly in public: to speak of any violations that are taking place that might displace so many people.

You’ve been documenting devastating themes since the beginning of your career. Self-care as a buzzword is quite a recent term, but have you been practicing it from the beginning? Can you give us any insights into how you practise it?

I’m depleted as we speak! I try to exercise and do other activities. Self-care is political. Also it depends if you’re able to, if you have all the tools of support that you need in order for one to self-care. It’s complicated, at this minute in my life. I’m processing a lot of pain. Other people’s pain that I’ve been carrying as I journey through spaces photographing others. The stories that I’ve heard, the spaces I’ve been to. It’s left a mark that I cannot delete.

How do you relax during your downtime? Do you ever have downtime?

I try. Nature a lot with my partner. We play boardgames – Scrabble! And we try to walk as much as we can.

Miss D’vine II 2007

Lambda print

765 x 765 mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

What is your message to any survivors of trauma interested in seeing your work as a means of potentially healing but who are afraid of being triggered?

To avoid the triggers, give yourself time. If there’s situation that might cause that [reflex], try by all means to distance yourself from it in order to avoid further hurt. Because you don’t want to be faced by a situation that puts you off. You have to protect your thoughts, and try to keep a distance, for personal sake.

What do you hope people struggling with their sexuality, and/or gender identity, and/or living in a heterosexist society take from the show. Do you hope they’re inspired?

I hope people try to find communities where they find solace. Where there won’t be negative energies shared with them. To avoid being alone. Because loneliness sometimes is dangerous. That’s when you think a lot about what’s happening in your life and what’s not. If you could try to form alliances and safer spaces in which we could express ourselves without fear of further prejudice – form communities for safety’s sake. Where you’re able to laugh again, and love without fear.

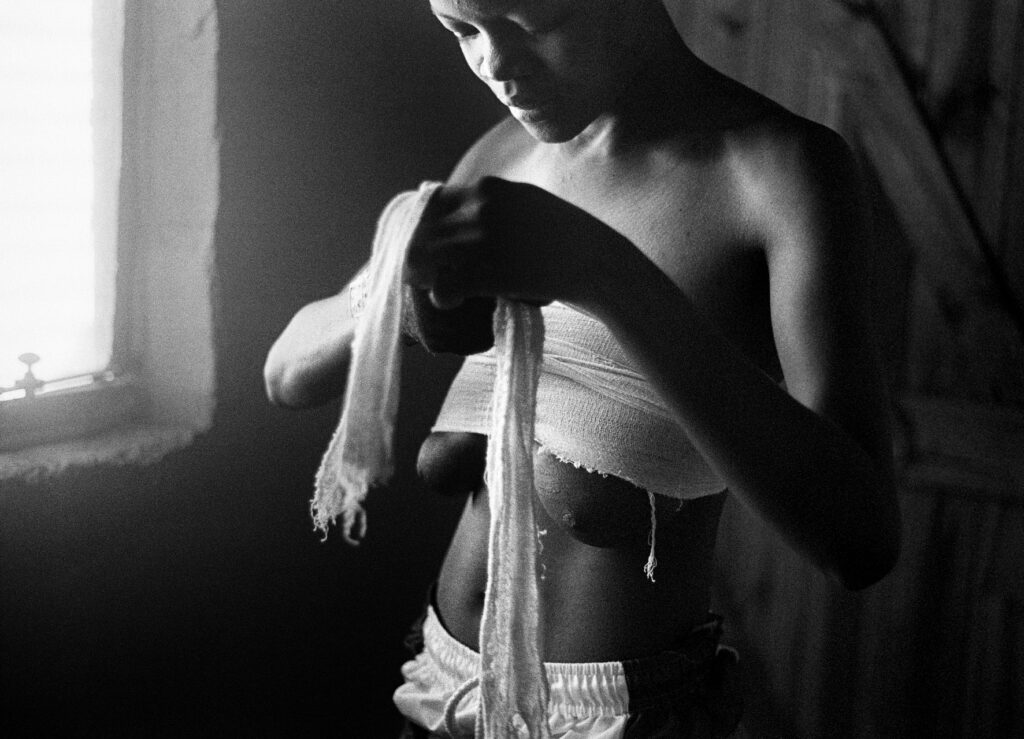

ID Crisis 2003

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

325 x 485 mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

You’ve visited many countries around the world with your work. What is the most remote place you’ve exhibited? How was the work received differently there as opposed to, say, a city?

My work was part of an exhibition in Dakar [the capital city of Senegal]. They had to shut down. My work, and the work of another artist who was part of the show – obviously it was a place where same-sex [sex] isn’t allowed. I can’t even say remote, because remote, really is something else.

There’s a General Election in the UK on 7 July. This week the ruling Conservative government announced plans to change the legal definition of sex to biological sex and restrict trans people’s access to public spaces. It is painful that this is happening the week your show is beginning. What is your response to the news?

It’s painful, because that backlash is harmful to many. I think there are a lot of politics that our governments should be focusing on than this topic. Care and healthy comments are supposed to be shared with our public. If people who are in positions of power care less, and share information that dents or diminishes another person’s life, it means that we’re losing battles and milestones won for us to get to where we are. I could say that respectful human rights is very, very important. Because then, all these new laws that are put in place, they violate people. And it means that whatever gains we’ve won seem futile.

I so wish we don’t have to fight anymore. I so wish, when we speak of freedoms, we speak it with our own minds. Where we don’t have to be challenged by haters. Because these are people born by parents who love them. Parents who try to care for their own. I’m not talking of situations where people are evicted from homes. I’m talking from the point of view where parents, and parents [including and] not limited to guardians, who are failing to support their own simply because of the high powers in place.

The public figures who have more voice than others. There shouldn’t be any trans child leaving school just because of the laws that are put in place that exclude the child. Because it means the future of the child is already affected, simply because of being excluded. That’s why we need further education. To ensure everyone gets sense. That they’re made aware that discrimination and violation of others who are different is not needed. It shouldn’t be tolerated.

I hope those culture war-stoking politicians come and see the show. Is that an invitation you’d like to extend to them?

Everybody’s welcome. If, maybe, their way of looking at things changes, people’s perceptions, then I’m happy. But if people come here to further project hate, they’re not welcome. Their actions displace many people, their violations hurt so many. We want peace. We don’t exist to be hurt 24/7. Just like any other person who’s got rights, who’s able to love and capable of receiving love, let’s preach peace. Use love and freedom.

Julile I, Parktown, Johannesburg 2016

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

660 x 1000 mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Could you speak to the importance for young people, all people, to vote?

Your political vote is very important. If you don’t vote, it means you’ll be defeated. It means decision-makers might decide on whatever they like, because of losing that particular vote. They say your vote is your voice. For a better change, or a better future. It’s important we preach and exercise that right, because it’s concerning when there’s corruption in spaces. When there’s exclusion and violence in spaces. But with that particular voice, change will come.

Out of curiosity, when you discuss your work, do you always use the proper titles, or do use descriptors, or nicknames?

Most of the series is titled in Zulu, which is my mother tongue. I’m deliberate, you know? The titles as they are, are very important. They describe the scene, or the sub-theme, or something in addition. Each name has its own meaning.

Zanele Muholi

Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg 2007

Photograph, inkjet on paper

765 x 765 mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Do you ever take pictures that are for your eyes only? Or as gifts for others?

There are many images that are not known, that have not been seen. But most of what I’ve captured, I was intentional. The images were aimed at being seen widely. For people to remember themselves, for photographers to remember it’s OK to be in front of the camera, [not] always behind the camera! But for your eyes only? I’m [not sure] about that. The images need to be shown. They need to be aimed at educating different publics about what is going on in other parts of the world. But most importantly, to help us learn how to love ourselves again. Because we don’t [need] any external validation from other people. For once, take a look at yourself, and give thanks for living. For the fact we’re here now.

What role does self-editing take? Do you ever take a bad photo?

A lot of ‘bad’ photos are taken. But you have to love them. What might come across as good to me is bad to you. It depends how we trust ourselves to read the images.

You’ve documented a lot of changes in South Africa over the last 20 years. What are your hopes for it in the next two decades?

A peaceful space where there’s no need to fight anymore. Where there’s no need for people to protest for better lives. I wish that we have as many books as possible to further this knowledge. I don’t know how much of a Black, queer and trans presence there is here in the UK that’s accessible to all publics, or people who just leave because of the assumption that you are free.

How much information like this could fill up a space like that in this very place? I long for a better South Africa where we don’t have to struggle for basic things. The hierarchy of life, of needs. Good housing. Good food system. Better health structures in place. Good education for all. Basic things. If people have no homes, focusing becomes a challenge. If there’s no better education system in place, then the future of employment is made impossible. Creating balance where we are free to be who we are without fear of any possible attacks.

Are there any talking points I’ve missed you’d like to cover?

There’s an ongoing project where there’s a need for photography and interviews. There’s a room with some people who are sharing their stories. How they became. Why they agreed to participate. What they do. Sharing their professions. I suggest that you give yourself some time and listen to what people are saying.