John O’Ceallaigh on the highs and lows of being a travel writer

Following a sheltered upbringing in Galway, John O'Ceallaigh has become a force within the luxury travel market and the leader on the Attitude 101 empowered by Bentley's travel list

As someone who was born in the early 80s, I occasionally take offence to being classified by marketers as a ‘geriatric millennial’. But then I hear myself telling younger friends what gay life was like in the last century and I realise that I’m a dinosaur, so the fossilising term makes sense. Still, the past is always a good place to start when trying to make sense of the people we are today, so I’ll kick things off with a short history lesson which explains a little about how travel saved — and made — me, as I lead the travel category of this year’s Attitude 101, empowered by Bentley.

I was raised in Galway in the west of Ireland. Nowadays (‘nowadays’ is a very geriatric thing to say), when I tell people where I’m from, the response from anyone who’s visited is invariably effusive, and rightly so: the coastal city is Ireland’s cultural capital, packed with pubs and alive with music and art from Monday to Sunday.

Summer is one long string of festivals. You’re an easy drive from some of the most beautiful and poetic landscapes in the country too, from Connemara’s heathered mountains and marshlands quilted with drifts of bog cotton to the Burren’s ancient tombs and the Aran Islands’ foreboding, elemental landscapes.

Plus, it’s really gay-friendly, as you’d assume of a prosperous Western European nation that was the first country to approve gay marriage as the result of a public referendum and which has long had an openly gay prime minister. You should go!

But that isn’t the Galway or Ireland I grew up in. Despite our present-day secularism, our culture is rooted in staunch Catholicism.

Homosexuality was illegal in Ireland until 1993 (divorce until 1996 and abortion until 2018). At that time there was very little wealth or economic opportunity, so immigration was minimal, and the non-existence of budget flights meant most of us stayed on our island with little first-hand exposure to realities beyond our own.

Summer holidays for me entailed (much-enjoyed) walks to the beach and drives to see nearby family. We had two TV channels growing up, and pretty much everybody seemed to look like me and talk like me and do the same things as me.

But each of us who’s gay can remember that niggle, an inkling that we were different. If you’re of my generation, that difference might have been described as something that “wasn’t quite right”. I was completely isolated as I tried to navigate this identity that was knuckling its way, unbidden and misunderstood, into my consciousness.

The gay culture I came to know about in Ireland in the 90s was furtive and shame-ridden for so many of the older men around me. Back then, I could never have predicted how far my homeland would subsequently come, and I wanted out. The idea of building a life in the travel industry, with its promise of fresh horizons and new people, became a kind of refuge for me.

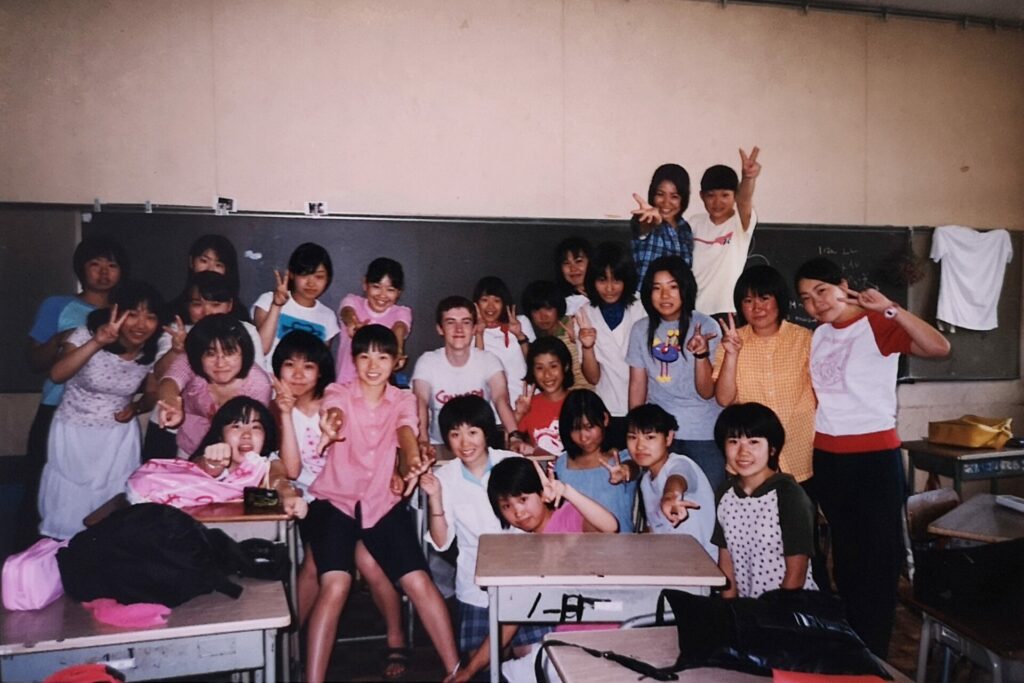

I’d figured travel could be my escape route because of an unusual experience I had when I was 16. I had written an essay to apply for a scholarship to be a youth ambassador to Japan for Ireland. I won, and so I spent that summer attending a Japanese high school in a small town in Nagano, where I gave numerous presentations and interviews telling people where my homeland was and then explaining why they might like to visit.

I recall a meeting with a regional mayor, being interviewed by a newspaper, and an appearance on TV. For my infomercials on Irish music, I remember pressing play on CDs featuring snippets of The Corrs, Samantha Mumba, Westlife and B*Witched — quite a camp compilation looking back. I still listen to all of them.

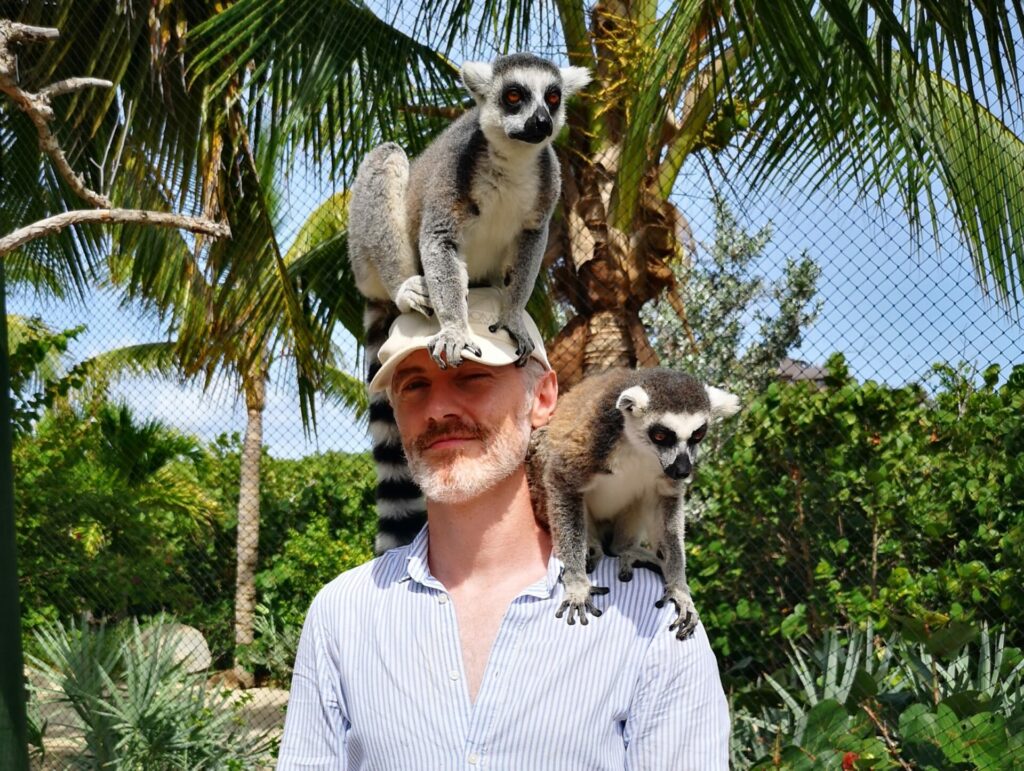

I also had the weird experience there of becoming a mini celebrity. My Japanese classmates lived in an untouristed part of the country, and most had never been abroad. It seemed to become a somewhat awkward thing that the other teens around me wanted to see my blue eyes — a total novelty for them. (That might sound ridiculous, but this was before reliable internet access was a thing, let alone having Google Images.) As the palest person seemingly for miles around, I received uncomfortable compliments for looking “like milk”, for my “skin spots” (meaning freckles) and “big nose”.

Every day, people commended the things I was most self-conscious about. It was bizarre, but trite as it sounds, it was perhaps the first time I was taught that what makes us different can be what gives us character and makes us special. On a subconscious level, that helped give me some hope when there was another point of difference within me that I didn’t yet accept and wasn’t sure I would ever take pride in.

I like how travel can challenge us and shape us and sometimes cause necessary discomfort when we’re confronted by our preconceptions and limitations. I was restless and unsettled when I returned to Galway. I initially complied with the majority of my friends and went to university in my home city, but the sameness started to suffocate me. I quit and moved to Ireland’s second city of Cork, where I somehow became a professional fundraiser for charity. I was good at it, so I was relocated to the Leeds office, where I helped establish the then-new practice of ‘chugging’.

Yorkshire may not be a globally recognised travel destination, but exploring the county was a revelation for me. I loved Leeds, and it is still one of my favourite British cities. This was my first time living somewhere with a proper, out-and-proud gay scene, and I jumped in enthusiastically. We went boozing in Fibre and Queens Court throughout the week, and I got into clubbing at the now defunct but legendary Speed Queen, which was a staunch supporter of LGBTQ+ inclusivity.

I was also around for the launch of the raucous Federation party, where masses of gay people would gather for hedonistic all-nighters. It was so exciting, and those crowds were my first real-world exposure to the breadth of the gay community and how much commercial power we wield.

When I moved to Manchester for university, for a while I was a waiter at the gay bar Via Fossa on Canal Street, where I started to make more gay friends and explore relationships. I remember working with many other young gay Europeans who had sought refuge from more conservative parts of the continent and had come to England to safely explore their identity — back then Britain really did stand out as one of the most progressive and tolerant countries in the world. It’s sad to think Brexit means the opportunities I benefited from have been rescinded for the generation that came after me.

Waitering during the academic year allowed me to finance summers spent backpacking. I interrailed through Eastern Europe and revelled in the freedom I had to head in new directions spontaneously, perhaps spending an afternoon ambling around Ljubljana (which was lovely) or spending another navigating Bratislava (grimy). I became more adventurous, subsequently spending months roaming Southeast Asia and zigzagging across India.

There were a few lows: some light kidnapping; being unwittingly enmeshed in a jewellery scam in Jaipur; becoming completely emaciated after suffering the most severe food poisoning imaginable in Kolkata; getting lost, pre-smartphone, in rural Laos; being robbed in Miami.

But they were offset by countless highs: the volcanic eruption in Iceland, when I climbed to a nearby mountaintop and saw the night sky glow end-of-the-world red and purple as bubbling lava sludged downwards and the earth began to steam; our ferry crashing through thick panes of ice as it cruised between Tallinn and Helsinki; just strolling from one extravagant plaza to another on my first visit to Rome, €1 scoop of gelato in hand and feeling drunk on all this endless beauty — I’m one of many clichéd travellers who has fallen head over heels for Italy, and for me its capital will always remain one of the world’s most beautiful cities.

I developed an addiction to travelling during that time, and after graduation I took a simplistic approach to determining my future: I wanted to travel and I could write, so I would be a travel writer. I’m often asked how to get into that profession, and while the perks are incredible — you stay in fascinating, beautiful places ‘for free’ — I advise caution.

The pay is derisory (in fact, it hasn’t increased in years, and with the cost-of-living crisis and ongoing inflation, it’s not uncommon that dedicating days or weeks to completing a job might mean you lose money), plus opportunities for professional progression are severely limited. In the long run, most people would do better to pursue another profession entirely to earn enough to travel in comfort privately.

That said, I was lucky. After interning at Attitude and elsewhere, I eventually got a job in London as the luxury travel editor at a national newspaper. It was an unusual turn of events: I had no exposure to this world as a youth and I wasn’t on my readers’ salary, so I had to quickly learn how to convincingly communicate with people who happily splurge £10,000 to £100,000, or more, per holiday.

I know those sums sound outrageous to many, and of course you can have a fantastic time away far more cheaply, but I quickly came to admire the many innovators and entrepreneurs who are working responsibly across the luxury travel industry. There are the hoteliers who renovate handsome heritage buildings that would otherwise fall into disrepair (think of The Ned in London, whose home had lain empty for eight years); the hospitality companies whose properly considered investments support local designers, artists and artisans (Peninsula Hotels’ Art in Resonance programme commissions emerging artists to create ambitious works for their properties); and the sustainability pioneers who are meaningfully protecting imperilled ecosystems (consider safari specialist Singita’s conservation efforts, or designer Bill Bensley’s Shinta Mani Wild in Cambodia, where profits are used to stop poaching).

I learned on the job: interviewing countless experts, commissioning stories, and admittedly enjoying a very indulged few years sampling outlandish travel experiences and outrageous signature suites. Ultimately, my outsider’s perspective and long tenure in the service industry proved to be valuable assets for me. The latter helped me appreciate exactly how much work goes on behind the scenes to deliver stellar hospitality; the former allowed me to recognise which experiences were truly distinctive and special rather than predictable and needlessly pretentious.

There are lots of hotels and restaurants that will slap some caviar or lobster on their menus so they can market themselves as a luxury property, but for me that approach is basic and boring. The real standouts work creatively with the heritage and culture of their locality to deliver memorable moments that would be impossible to replicate elsewhere.

It’s the contradictory experience I accumulated as a modestly paid travel writer, who might go on trips with a combined retail value in the hundreds of thousands of pounds in any given year, that led me to establish my own company, LUTE, right before the pandemic — not a great time to kickstart a travel business.

Standing for ‘Luxury Travel Edit’, LUTE (lute.co) is a consultancy and content agency that advises luxury travel brands, or brands that aspire to operate in that sector, on things like creative strategies, emerging travel trends, competitor analysis and storytelling opportunities. We typically work with hotels, tour operators, airlines and tourist boards. To give an example of how that could work in more practical terms, I might visit a yet-to-open or underperforming property, assess what is and isn’t working, and propose a spread of new services, amenities and activities they could offer to clients to improve customer sentiment and capitalise on PR opportunities.

The content arm of LUTE deals with producing copy for websites, coffee-table books, press releases and so on, with contributions from world-class travel journalists instead of conventional branding-agency copywriters who tend to regurgitate luxury clichés rather than sharing inviting stories about what is really distinctive and special about a destination.

LUTE’s clients are based worldwide, including in destinations that aren’t completely LGBTQ+-friendly, like the Maldives. Sometimes there’s a friction here between hospitality companies and their host countries. The former will proudly proclaim they’re fully committed to inclusivity and welcome everybody; the latter might explicitly discriminate against the gay community. And often there’s an unspoken middle ground between the two entities, because both groups know those travellers are exceptionally valuable financially.

The World Travel and Tourism Council notes that the LGBTQ+ sector accounts for over 10 per cent of tourists globally and around 16 per cent of total travel spend. That’s why we’re often wooed by resorts that will assure us they’re a fully safe space while simultaneously advising us to exercise caution outside their properties.

Clearly, this isn’t ideal, but I believe travel is a force for good, and conversations I’ve had with clients during recent consultancy projects show me the situation is improving. More and more of them are asking for guidance on ways to meaningfully show sincere support for this audience, who are acknowledged more publicly than ever now in industry marketing. I’ve also seen signs of greater acceptance of gay rights among travel industry leaders operating in traditionally conservative countries, even if political sensitivities mean some aren’t able to share those sentiments publicly.

Ultimately, I believe progress will come because the luxury travel industry is packed with immensely successful and influential LGBTQ+ people, like Langham Hotels’ CEO Bob van den Oord and the aforementioned hotel designer Bill Bensley, who are precipitating change directly.

That’s readily obvious in places like London, where the Pride flag flies year-round (not just during Pride season) at the Shangri-La the Shard, London hotel. Its gay manager Kurt Macher’s inclusivity initiatives cover everything from comprehensive staff training in diversity to devising defined guest-service protocols for welcoming throuples (no need to worry about an insufficient number of slippers and robes being laid out at turndown here).

It’s interesting too to note that places like Malta, which was long a deeply traditional and Catholic country like Ireland, is now a world leader in LGBTQ+ rights and proactively and exuberantly courts gay travellers.

Reflecting on all that I’ve experienced through my work, it feels such a shame that working in travel and hospitality isn’t always recognised in Britain as a ‘proper profession’. I know so many industry veterans who have enjoyed incredibly exciting opportunities and who earn stacks of money.

If you’re reading this and would like to investigate opportunities in the sector, consider applying to one of the many hospitality courses out there, or speaking to some of the sector’s inclusivity-focused recruitment specialists like MyGWork or Lightning Travel Recruitment. Now’s a good time to make a change as so many major brands in the UK and globally are desperate for fresh staff after droves of employees changed careers during the pandemic.

Although the media feeds on bad news, the kind people I’ve met and the beautiful experiences I’ve been lucky to enjoy through my travels have had a profoundly positive impact on me and the way I see the world we share. I’ve been very lucky.

Attitude 101, empowered by Bentley is our list of the year’s 101 most influential LGBTQ+ people.

The 10 categories, each featuring 10 individuals, are Media & Broadcast, Film, TV, and Music supported by LA Tourism, Science, Technology, Engineering, & Mathematics (STEM), Third Sector & Community, Financial & Legal, Fashion, Art & Design, Sport, Travel, Business, and The Future supported by Clifford Chance.

The full travel list of Attitude 101, empowered by Bentley

John O’Ceallaigh – Founder of LUTE

Anthony Woodman – Vice president of Flying Club & CRM, Virgin Atlantic

Charlie Sprinkman – Founder, Everywhere is Queer

Dan Leveille – Founder, Equaldex

Jo Rzymowska – Non-executive director, Hays Travel

Thea Bardot – CEO, Lightning Travel Recruitment

Phillip Iveson – Commercial director, TUI

Natalie Thompson – Board member, WorldPride Washington, D.C. & InterPride

Keshav Suri – Executive director, Lalit Suri Hospitality Group

Max Aniort – Co-founder and CEO, Le Collectionist

This feature appears in issue 357 of Attitude magazine, available to order online here, and alongside 15 years of back issues on the free Attitude app.