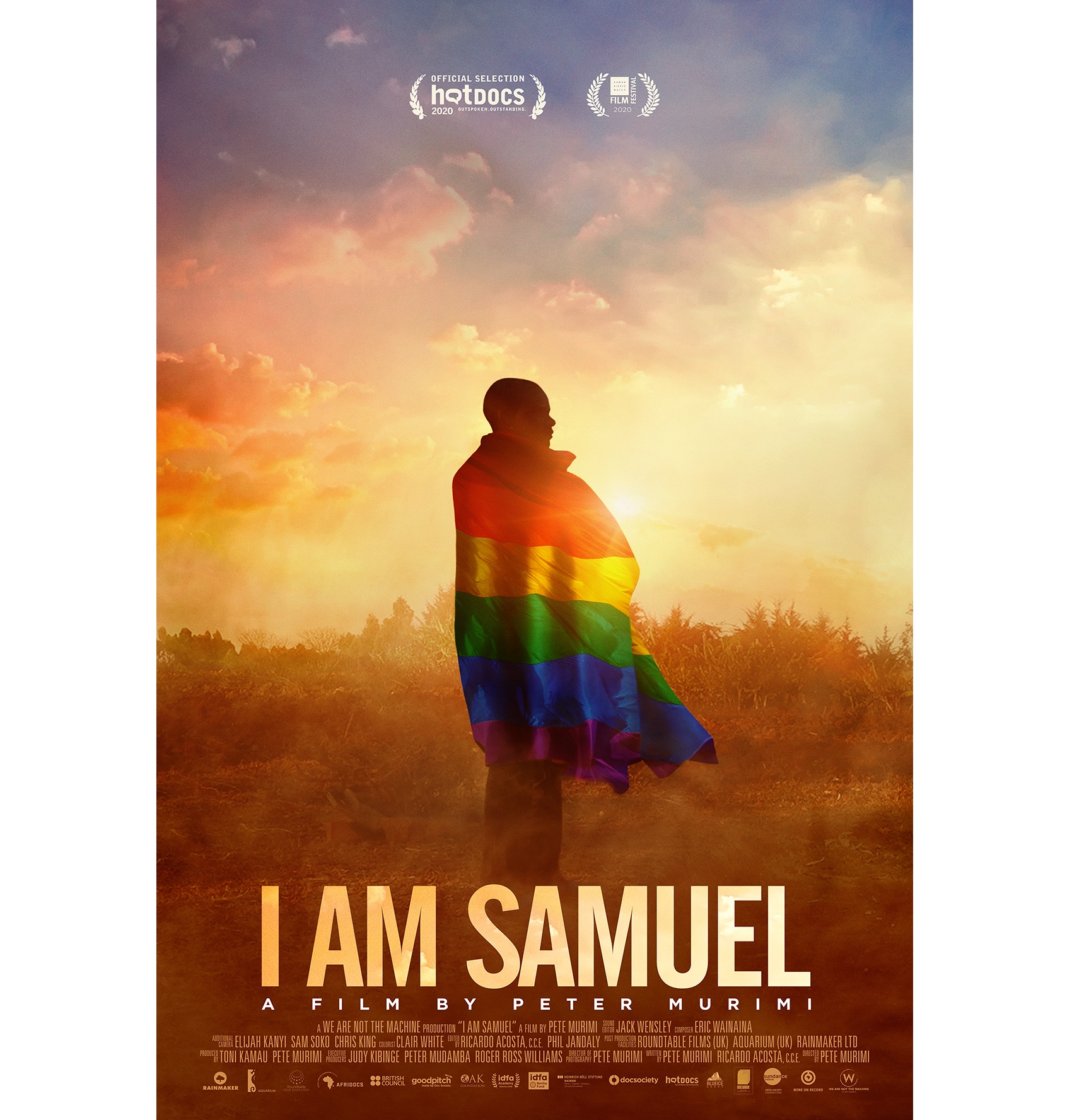

I Am Samuel: Inside the powerful gay documentary film now banned in Kenya

Shot over five years, the film charting the real-life struggles of a gay Kenyan and his partner was banned by Kenya’s Film Censorship Board in September 2021.

Words: Lerone Clarke-Oliver; Images: Supplied

This article first appeared in Attitude issue 334, March 2021, prior to being banned by Kenya’s Film Censorship Board (KFCB).

Kenya is considered to be one of the most progressive African nations. However, in 2019, the Kenyan High Court left LGBTQ+ activists disappointed when it upheld a colonial-era law that punishes homosexual acts with up to 14 years in prison.

Last year, the Gay & Lesbian Coalition of Kenya (GALCK) said that each month of the pandemic had seen up to ten reported attacks on the LGBTQ+ community. Although Kenya’s government raised the alarm about the increase in cases of gender-based-violence, it has not offered any help for LGBTQ+ people suffering this type of abuse.

Aerial shot of Nairobi, Kenya’s capital (Image: Supplied)

In the light of these headline-grabbing facts, a documentary filmmaker might be expected to focus their attention on the legal issues and harsh realities facing the queer community in Kenya. But in the film, I Am Samuel, director Peter Murimi presents a tender and authentic look at the lived reality of Samuel, a gay, Kenyan man, and his relationship with his partner, Alex, over a period of five years.

It’s the intimate access that makes this film so vital. Filmed against the context of Samuel’s family and their gradual understanding of their son’s identity, the documentary sensitively explores Black, African, same-sex love, while also touching on resilience, masculinity and community. As it does so, it subtly reminds us that queer love exists everywhere, and that love can find a way.

Samuel and Alex travelling to visit Samuel’s parents, who live in rural Kenya (Image: Supplied)

Although I Am Samuel documents the touching and romantic journey of two Kenyan men that have found love against the odds, it isn’t always easy viewing. The contrast between Samuel and his friends’ lifestyles and ours is stark. Samuel is not wealthy. He has little access to the things we take for granted. In the West, our struggles are focused on the fight for same-sex marriage, adoption and surrogacy equality, or access to healthcare. For others around the world, liberation isn’t about equal rights; it’s simply about human rights. In Kenya, Samuel can be imprisoned, attacked, tortured or killed just for being his authentic self. For the country’s LGBTQ+ community, life has a volatile quality – the fear of violence, an ever-present danger, is part of their everyday experience. But in spite of all this, so is love, friendship and hope.

Despite our cultural and economic differences, it is revelatory to discover some surprising similarities between Samuel’s life and our own. The backdrop may be different, but from the monotony of work and reluctant birthday celebrations, to career aspirations and patrilineal strain, the film’s themes are familiar, with chosen family at its core. It’s in these moments that we see a queer man who is, in fact, much like us.

Samuel playing netball with his friends as the sun sets on Nairobi (Image: Supplied)

When I speak to Samuel, who still lives in Kenya, he initially comes across as a shy, coy man. However, when we speak about his relationship with Alex, his voice shines. It’s charming to witness these young men finding so much joy in each other’s company.

Romance aside, though, I’m curious as to why Samuel, Alex and his friends decided to be part of such an important project that is also unquestionably hazardous since their identities are not hidden on film (as we have done for this feature).

I Am Samuel has yet to be screened in Kenya, but there is the risk that the underground LGBTQ+ community may be more vulnerable as a result.

“It is important for us to be seen,” says Samuel, explaining that he doesn’t underestimate the film’s power. “It shows queerness that is not threatening.”

Despite Samuel’s documented strained relationship with his father, Samuel never — in the film nor in our conversation — presents himself as a victim. Instead, he is someone who wants the best for his loved ones and is simply exploring the possibilities of the world around him — and how best to navigate it. “As more gay people come out, tolerance will spread,” he says affirmatively.

Samuel and Alex (Image: Supplied)

It is hoped that the film will also help to change attitudes in Kenyan society — indeed, that has been Peter’s aim from the outset.

A multi-award-winning documentary filmmaker who is also from Kenya, Peter describes himself as a passionate storyteller who is committed to putting the African narrative on the global stage. A previous recipient of the CNN African Journalist of the Year award, he has been a documentary maker for more than 15 years and is known for highlighting social issues – from police extra-judicial killings to sex work and female genital mutilation. In I Am Samuel, Peter addresses Kenya’s on-going resistance to embracing the marginalised LGBTQ+ communities with admirable frankness.

Director Peter Murimi hopes the film will help LGBTQ+ Kenyans (Image: Supplied)

When Peter and I speak, he exudes paternal warmth. His manner is gentle — clearly, he’s a kind, empathetic and considered man. Peter isn’t LGBTQ+, but is well aware of the struggles that queer people face in his native country. We discuss the film’s themes: societal expectations; violence; love; the relationship between a father and son; generational disparities; the hypocrisy and irony that exists in religion; and the enduring impact of colonialism. We also touch on the current discourse around whether non-LGBTQ+ filmmakers should take on the stories of LGBTQ+ people, a question that has become almost a ‘checkmate’ within the queer space.

He has a very straightforward response: “Someone close to me was struggling with his identity, and his family was finding it hard to accept. As a filmmaker, I knew that something like I Am Samuel would help, but it didn’t exist at the time. I had to ask

myself, what can I do to help people like my friend, people like Samuel? When a straight [Kenyan], man or woman, especially from the church, speaks on LGBTQ+ rights, people listen. It is very wrong for me as a Kenyan to see other Kenyans have their rights disenfranchised and do nothing.”

Peter hopes that I Am Samuel will bring people together for “constructive dialogue about LGBTQ+ rights” and for people to understand that “you can be African and LGBTQ+”.

Baptism ceremony in Samuel’s village. Samuel comes from a very religious family, and was baptised in the same river as a teenager (Image: Supplied)

It’s a situation that Kenyan LGBTQ+ activist and journalist Kevin Mwachiro knows all too well. Kevin, who also serves on the Gay & Lesbian Coalition Board of Kenya and is on the board of Amnesty International, says of the film, “I was blown over! It is phenomenal and powerful because we’re being seen as regular people; that will make authorities uncomfortable because it shows Kenyans for who we are.”

He firmly shares Peter’s vision that the documentary will help others, both Kenyans and other Africans. “Absolutely, I Am Samuel can and will be used as a resource for queer African people. It really shows the reality of a queer Kenyan couple and it uses local languages. We will be able to relate; it says ‘gay Kenyans are here!’”

Samuel’s parents praying for Samuel and Alex before they depart for Nairobi (Image: Supplied)

It’s a story that is rarely told and it has been depicted with care. Before I Am Samuel was shot, Kevin met Peter and producer Toni Kamau and so trusted and knew them both well. Kevin saw several rough cuts of the documentary and was able to offer feedback, insight and support over the five years it took to complete. As a community consultant, he became the sounding board that allowed the documentary to circumvent any voyeuristic or exploitative undertones that other documentary films such as Paris is Burning or A Portrait of Jason have

been criticised for.

Kevin, Peter and even Samuel all downplay their roles in the film, and there is an unspoken sense that this is bigger than all of them, that no one was in it for any reason other than to document the queer, Black, Kenyan LGBTQ+ community.

An aerial shot of rural Kenya, where Samuel’s parents live

There’s no denying that Kenya is in a state of flux. Although its law against “unnatural offences” has rarely been enforced in recent years, in 2021, homosexuality remains illegal. Homophobia is institutionalised and has certainly contributed to violence. Activists say many are afraid to report abuse or to seek medical help because of stigma. Kevin points to other African nations that have decriminalised homosexuality, but are still seeing the same level of LGBTQ+ hate crimes — which go uninvestigated by authorities.

Yet both Peter and Kevin point out the disparity between those that live in the city and those who reside in rural areas, where Samuel’s parents live. There is some evidence of progress: thriving queer film festivals, LGBTQ+ sports teams, organisations and religious leaders who are finally engaged in conversation with Kenya’s queer community leaders.

On the surface, I Am Samuel is a film about love flourishing against the odds, however, at its core is a message of resilience, pride and the significance of community — whether that be our families, our partners or our allies.

“We are all Kenyan; I want queer Kenyans to know they are not alone,” Peter adds. If I Am Samuel becomes the beacon of hope and support its protagonists and makers hope it will be, we can be sure that this is not where Kenya’s LGBTQ+ story ends.

I Am Samuel is out now to stream on BFI Player.