Paul Flynn: ‘How five moments in LGBT+ history have impacted my life’

By Joshua Haigh

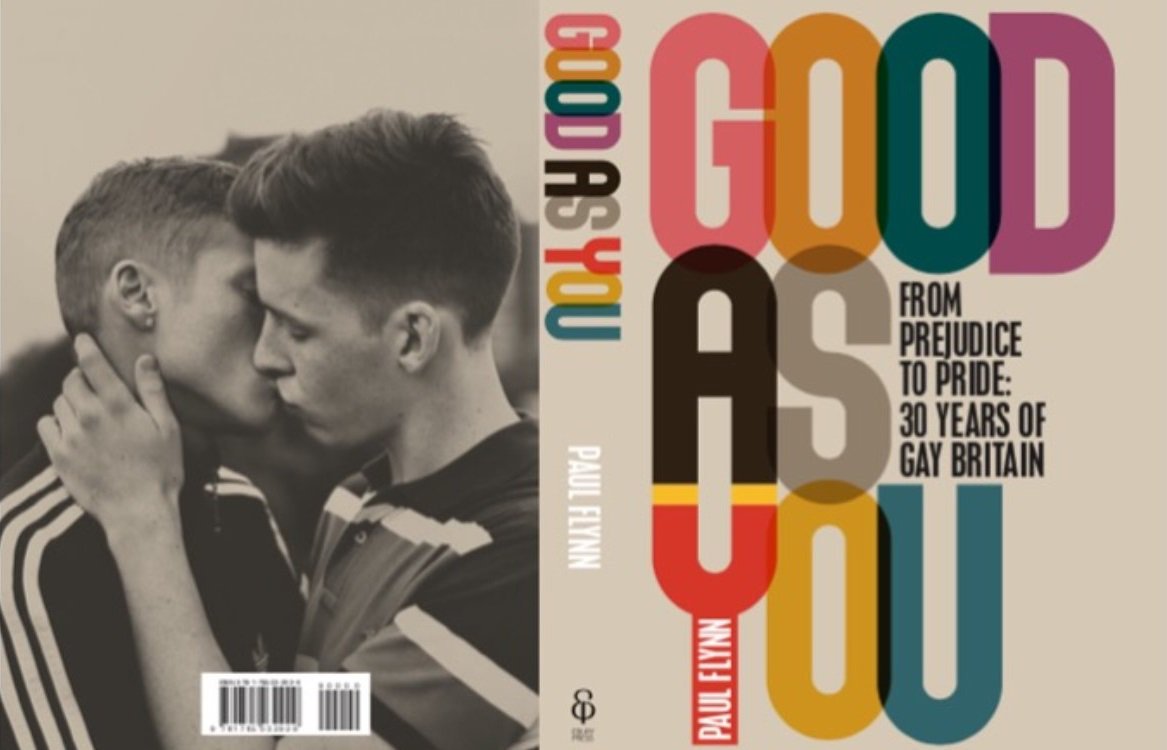

With the release of his book Good As You: From Prejudice to Pride – 30 Years of Gay Britain tomorrow (April 27), writer Paul Flynn and Attitude columnist has opened up to Attitude about the five most personal of gay history in his lifetime – take a look below:

The release of Bronski Beat’s Smalltown Boy, 1984

I was just about to turn 13 when I heard Smalltown Boy for the first time. It blew my tiny mind. I knew exactly what the message of the song was from the opening four notes. It is one of those highly specific pieces of music that lives in melody as in words. The opening couplets about standing alone on a cold and windy platform place the idea of gay escape in a specific, literal location. I don’t think I’ve stood at a train station since – and I’ve stood at many – not being reminded of that image of Jimmy Somerville and the little flight case in which he’s packed his hopes and dreams, because ‘the love that you need will never be found at home’. He was the first gay man I could directly relate to. He was not just open about his sexuality but there was tenacity and defiance to him, too; this beautiful, small whippersnapper of a man channelling the voice of the gods in song, with a haircut I wanted to have, in clothes I wanted to wear. I recently interviewed the amazing designer Martine Rose, who had dressed Jimmy in a glitterball bodysuit for an art project and she described him as the nearest Britain ever got to finding its own Donna Summer. I couldn’t argue with that.

The Section 28 demonstration, Manchester, 1988

My predominant memory of the then most well-attended political rally in my home city was of mainly trying to avoid the BBC and Granada Reports film cameras, in case my mum caught a glimpse of me on the news. I was 17. The speeches from the platform in Albert Square spelled out exactly what I needed to know about discrimination in five easy pieces. The speakers were Sir Ian McKellan, then plain old Ian; Graham Stringer, leader of Manchester City Council; Michael Cashman, Colin from Colin and Barry off Eastenders; Sue Johnston, Brookside mum; then Tom Robinson leading 20,000 allies in a moving chorus of Glad To Be Gay, a moment that sounded more like the nearby terraces of Old Trafford and Maine Road than it did a mass collection of ennobled woofters and their pals with placards and poppers. It was a moment that changed Manchester – and in its own way, the nature of British protest – forever. The invisible had become visible. There were a lot of us about.

The release of Paris is Burning, 1990

You can tie Jennie Livingston’s Voguing documentary Paris is Burning to pretty much all of my favourite things in pop culture. On the surface, it is a simple story; the culmination of everything great about New York’s ferocious ownership of fashion, art, street and nightclub culture from the previous decade. Yet it is peopled by a cast list, Octavia St Laurent, Willi Ninja, Pepper LaBeija, Venus Extravaganza who embodied all the elegance, humanity, poise and sophistication that distils in DIY gay culture at its closest to perfection. In heartbreak: drama. In death: rebirth. In rejection: beauty. In life: dance. Without the unique Harlem Vogue ball scene, there would have been no Blonde Ambition or Malcolm McClarem’s Waltz Darling, two of my very favourite cultural occasions and artefacts, ever. There would absolutely be no RuPaul’s Drag Race. Yet over the years, as Paris is Burning has become enshrined in a finely woven historic veil, becoming every bit as legendary as its children imagined themselves in their minds, this central cast have begun to feel like the forbears and saints watching over gay culture as it swept from the margins to the mainstream. They, and Livingston are every bit as crucial to our story as Edmund White, Armistead Maupin or Oscar Wilde.

The civil partnership of Elton John and David Furnish, 2005

Hands down this was the most glamorous party I’ve ever been to. It was so glamorous that for six months afterwards I couldn’t actually go to any other parties. I stood next to royalty for the first and possibly last time ever. The most remarkable thing about how glamorous this night was how brilliantly, beautifully local it all felt. British gay history was changing that night in a Windsor Marquee and it had the figureheads to prove it. David Furnish had stepped up to the platform no gay spouse had done before, making his name organically known; so that the idea of two men in love that sits ethereally over all our families as we introduce the next boyfriend had a pair of names and faces to which we could point and say, it’s OK, it’s not unusual. Elton John is absolutely bar none my family’s musical hero. If I only had to listen to one artist, ever, for the rest of my life it would be him. He is loved by all the right people for all the right reasons, because his approach to life and to the gay community is not to build walls but bridges, to extend a hand of friendship, to invite everyone along to the party, whether that be to hip hop, Russia or football. To watch him extend that untrammelled global capacity for union into his intimate life was just astonishing. I can still recount almost every word of the speeches. I met Elizabeth Hurley. Sorry, it matters.

The death of Alexander McQueen, 2010

I had been due to interview Lee McQueen for the American website The Daily Beast on February 13th. On the 10th, the interview was indefinitely postponed. On 11th he was found dead in his Mayfair lodgings. The whys and wherefores of McQueen’s life will be picked over forever. They are a useful arbiter into so many of the preoccupations that activate forward buttons in British gay culture, forever taking boundless leaps into the unknown, forever reinventing its own minority wheel and spreading that taste and purpose far beyond its ken. There is one certain timeline within it and in that narrow timeframe, McQueen upended British culture over and over, lending it exquisite new levels of taste, excellence and drama. McQueen was a once in a lifetime fashion designer. More than that, he was a cabbie’s son from East London who by sheer dint of his talent alone became a new watermark for British brilliance. Yet the country of his birth, pockmarked with a history of homophobia, could not keep him alive. You always want these stories, of personal heroes who excel at everything to be the last premature death of a gay man. You know they won’t be, until everyone sits up and addresses not a version of what happened in his life away from the runway but the stark actualities of it. RIP.

Good As You: From Prejudice to Pride – 30 Years of Gay Britain by Paul Flynn. (Ebury Press, £20)