Founders of UK’s oldest HIV charity recall early days of the AIDS crisis

Dr. Rupert Whitaker OBE and Martyn Butler OBE are among the everyday LGBTQ heroes honoured at the Attitude Pride Awards 2022, in association with Magnum.

Words: Alastair James; Photography: Markus Bidaux and Ieuan Berry

Terrence “Terry” Higgins died on 4 July 1982. He was one of the first people in the UK to die from an Aids-related illness. But his death ignited the flame that became the Terrence Higgins Trust (THT), which has spearheaded advances in the care and treatment of people living with HIV.

Those last three words being the most important — people with HIV can live as long as someone who doesn’t have it, thanks to the work of the Trust (and others).

In an acknowledgment of this, its founders, Dr. Rupert Whitaker and Martyn Butler were recently awarded an OBE each for their services to charity and public health.

Naturally, the Trust’s story begins with the man in whose memory it was founded. Butler, 68, met Higgins, a fellow Welshman, in Soho after Butler moved to London at 16 and got a job with the film studio Warner Bros in Leicester Square. He and Higgins bonded over their mutual love of music and clubbing.

“We didn’t [approach] nightclubbing on a very superficial level. We knew the record producers, we knew who was singing on the tracks, we knew when they were likely to tour. Terry used to fly to the US and bring back exclusive DJ remixes, which were worth their weight in gold. And he’d sell them among DJs here,” remembers Butler.

The two developed a close friendship, and Higgins became something of a mentor. “The greatest thing Terry taught me was how to tell people to fuck off. I’d never been able to, but it was liberating. I was in Heaven making new friends, and Terry says, ‘If that guy is getting on your nerves and you don’t want him, why are you putting up with it?’ Terry was able to tell me to own my space,” Butler recalls.

Whitaker, 59, met Higgins in the summer of 1981 when he was 18 and about to head off to Durham University. Shy and lacking in confidence, one night he plucked up the courage to go to Bang nightclub on Charing Cross Road.

“There was this guy dancing on his own having a great time. And I was mesmerised. He looked like a human slinky and I didn’t know legs could actually do that,” Whitaker tells us with a gentle laugh in his voice as he recounts when he first saw Higgins.

The pair became a couple. “He was loving, warm, and fun and he had a really naughty sense of how to enjoy life,” says Whitaker, smiling fondly. “He didn’t take anything too seriously and he gave me a security blanket which I really needed at that time. He had a great sense of humour, and he really was one of those people who would give you the shirt off his back.”

Sadly, they only had about a year together before Higgins passed away.

Dr. Rupert Whitaker OBE (Photo: Markus Bidaux)

A couple of months later, Butler called a meeting in his east London flat. Here, the Terry Higgins Trust was born (later becoming the Terrence Higgins Trust). Butler says, “I made a promise that nobody needs to go through [Aids] on their own.”

Whitaker adds, “I personally didn’t want other people to go through what I had gone through. We all came together with our own commitment to make a difference. So, we tried to do that.”

In the early days, there were a number of obstacles. Butler tells me of one experience, captured by Russell T Davies in his Channel 4 Aids epic, It’s a Sin, where leaflet distributors are hustled out of a gay bar for trying to raise awareness.

Only, Butler stresses, the reality was very different. “It was actually quite violent. They threw me out of the place. And my leaflets after me. The level of aggression was vastly underplayed.”

Many in the gay community accused Butler and co. of trying to put the genie back in the bottle after gay liberation, while others, as Whitaker notes, were terrified and not sure how to cope as people began to “drop like flies”.

Disturbing, too, were the attitudes of doctors. “You’ve got nothing to offer,” Whitaker was told by NHS physicians who arrogantly assumed they knew everything about this new plague. Butler remembers visiting a friend on an Aids ward who was all but neglected by nursing staff.

“The contempt and neglect were vile,” Whitaker says. He also adds that classism was another barrier he came up against as the fledgling organisation began to grow.

Martyn Butler OBE (Photo: Ieuan Berry)

But through all this, the charity was established. Educational resources were printed, and counselling services and phone lines set up. Now, we have effective treatment for those who are HIV-positive — PrEP, which prevents millions from contracting HIV in the first place — and regular testing. But looking back, 40 years later, isn’t easy.

Although Whitaker highlights the positive changes as well as the way the fight against HIV and Aids helped humanise the gay community, leading to marriage equality and the like, he worries for the future.

“Our progress is fragile, and we need to understand that. We need to continue to push hard to really embed progress that we have made because of the losses through Aids. We really need to be aware of that.”

Butler, while proud of his accomplishments, surprisingly wishes the organisation wasn’t around today. “I wanted to close down the Trust. There’s nothing sinister in that. It was purely a case that I would know that we had been successful when we’re not needed any more. I do look forward to that day. If we didn’t need it, how wonderful would that be? That’s all.”

As for receiving an Attitude Pride Award, both men are humbled.

Whitaker says, “It’s really difficult to imagine that the effort we have made would be recognised in so many ways today. It’s wonderful to be able to say thank you and to say that we still need to keep fighting and pushing to make sure that all the progress we have made we keep. And personally, I feel really chuffed.”

Butler’s biggest worry, in the beginning, was he’d “fuck it up”. Nothing could be further from the truth.

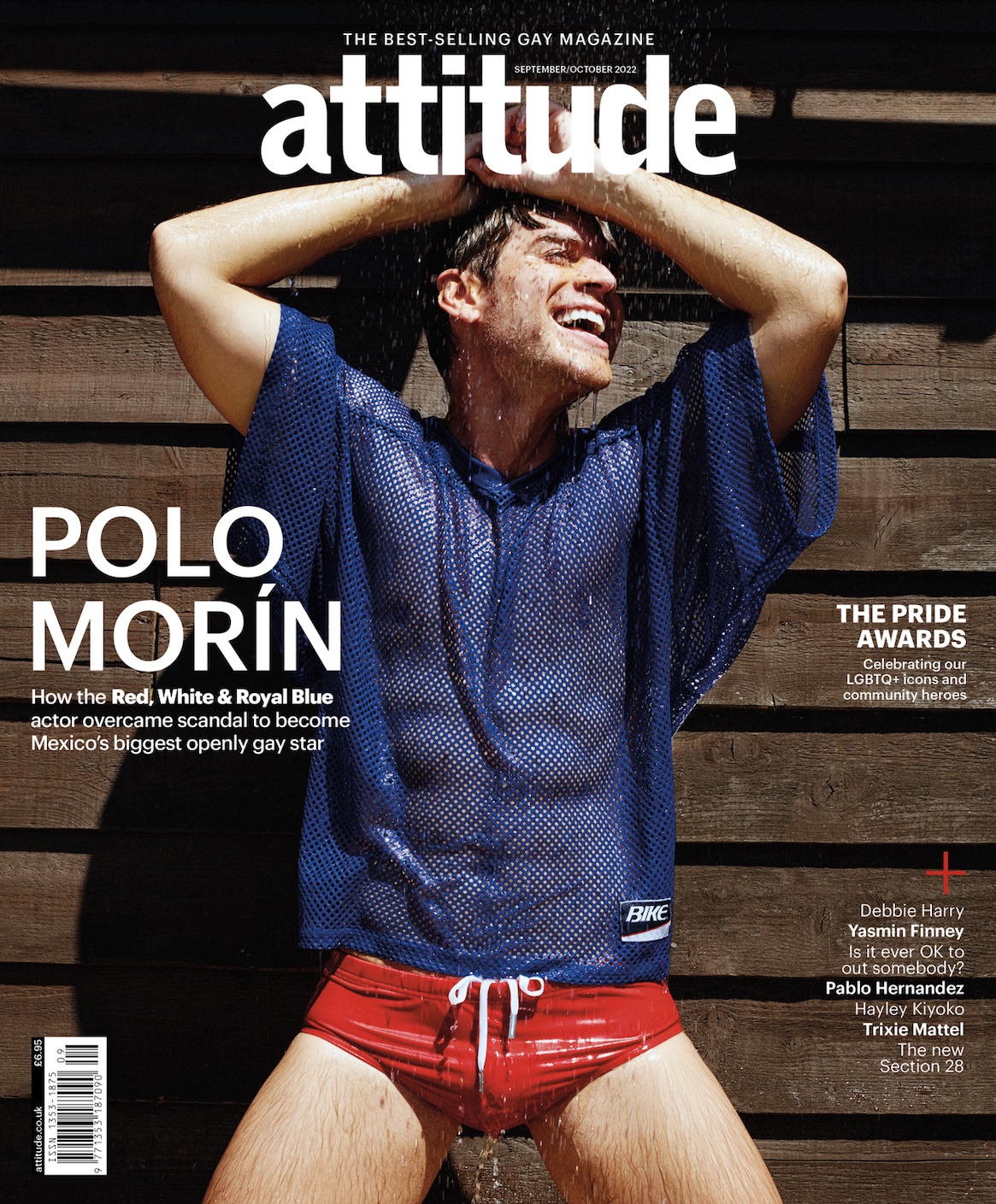

The Attitude September/October issue is available to download and order in print now and will be on newsstands from Thursday 4 August.