Interview | Meet the gay man teaching LGBT equality to kids at a 99% Muslim primary school

By Ben Kelly

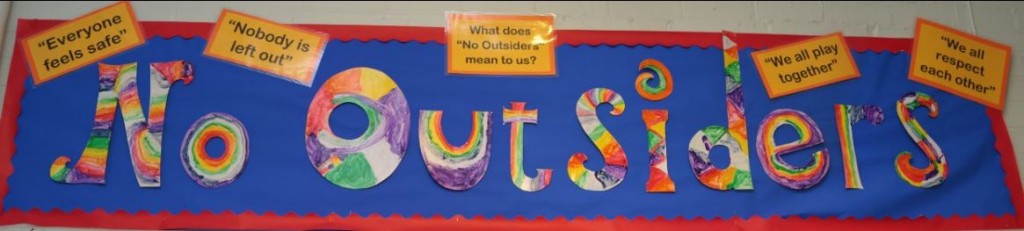

Andrew Moffat has been a primary school teacher for over 20 years, and is passionate about teaching LGBT equality to children through the guiding principles of Britain’s Equality Act – something he’s now outlined in his new book, No Outsiders In Our School.

Over the years, he has come up against resistance to his inclusive teaching style, and left his last school after facing vicious opposition from parents to his decision to be open with his students about his sexuality. Now, Andrew teaches at Parkfield Community School in Birmingham, where 98.9% of pupils are from Muslim families. We spoke to Andrew about how he’s applied his inclusive teaching technique to this setting,and the lessons that can be learnt…

Your new book is called No Outsiders in Our School, and it’s about how to successfully teach LGBT equality in schools. How did you come to champion this cause in the classroom?

I’ve been working for about ten years in challenging homophobia in primary schools. Schools are very good at doing work around gender and race equality, but LGBT equality was always the last one – and I’ve had difficulties with it myself too. So I’ve been doing this work through devising lesson plans, using picture books, and I had quite a bad experience at my last school where it went wrong, and I had to find a way to get it right. I started again, and I realised that what was needed, was for LGBT equality to be taught as part of all equalities. You really can’t do it by itself. It makes it more acceptable to people who are frightened of LGBT equality.

The bad experience you had at your last school was a result of you telling the kids you were gay, is that right?

Well that’s where it all came to a head, yes. I’d been doing the work there for a couple of years, but I hadn’t actually come out. I’d been teaching the No Outsiders stuff, but what I didn’t do was get the approval of the governors, or the parents – and the school were frightened of doing this work. So it was all fine until I got a complaint – and then, there was no back-up and I was vulnerable. So, in the book, I very clearly state the steps that teachers need to take to do this properly. You need to have governors on side, you need to have school policies on your side, then you get parents involved very early on. What you don’t want is to be accused of having an agenda, so you have to explain to the parents, and put it into context for them. You have to tell them that you’re not just teaching that it’s OK to be gay – it’s about teaching that in our school everyone is different, and that’s wonderful. We welcome everybody in our school whether they’re male or female, Christian or Muslin, gay or transgender.

The complaint at your previous school actually came from someone who objected on the grounds of their own Christian faith. You’re now teaching at a Birmingham school which is predominantly Muslin children. What was the response when you introduced this style of teaching there?

I chose this school on purpose, because I wanted to be in a school where I thought this work was most needed. I went in from day one and was very honest with the head teacher, and we had many discussions together about how we were going to do it, and get it right. There were difficulties at the beginning. A lot of parents were very worried about this work, so we met them in small groups and got them on side. There were some very challenging meetings, but we managed to convince the parents that it was the right thing to do, and that we weren’t threatening their faith. In the book, I lay out exactly how we did this, and a day-by-day plan of how we managed the whole thing across one year.

You say that you’re teaching the kids about LGBT equality, while not infringing on their religious teachings at home. How compatible can a respect for LGBT people be with an adherence to Islam?

What I’ve learned is that you can hold both views. I’m not telling children what they should think. I’m telling them that as they go through life, people are going to have different views and opinions, and the important thing is to have dialogue, and have respect for each other. We talk openly, and some children have told me that they find it difficult, but that’s fine with me. I’d rather we had that discussion, than not. But whatever different faiths think, the law in the UK – the Equality Act – includes everyone. That’s why we say in our school, there are no outsiders, and children talk often about how everyone is welcome.

Education Secretary Nicky Morgan said last year that homophobic comments may be one of the signs that a child is being radicalised, or is vulnerable to extremist views, and that teachers have a duty to report it. Do you feel that’s fair? Have you encountered it?

I wouldn’t agree. I wouldn’t say homophobic comments are a sign of that. What you need to do is teach children to celebrate living in the UK, that’s what it’s all about. It’s about teaching children that the UK is diverse, and that’s wonderful. You teach them to want to enjoy diversity.

The government has also been criticised in the last week for failing to make Sex and Relationships Education (SRE) statutory in schools. As a teacher, do you think the government should be implementing this?

[No Outsiders] is not SRE, it’s about teaching people about diversity. These are two completely different things. And you see, when we first started this, some parents thought it was sex education, and they didn’t want their children learning about that, and you really have to separate the two things. I make no mention of sex whatsoever in my ethos. It’s about different families, and different people, and people getting on. We get kids talking about people who have two daddies, or two mummies, or people being gay or transgender, and they’re talking confidently about that, and we’re not mentioning sex at all. So it’s really important that schools separate that, because it’s not about sex.

What would you say to other teachers who might not feel comfortable teaching these kinds of things, or indeed other gay teachers who might not want to be out with their students?

Fair enough. I’ve been there myself. I’ve been teaching for over 20 years, and for the majority of that, I wasn’t out. In my book, I write about how to come out at school, based on my own experiences at three different schools. It’s the school’s responsibility to make sure teachers can be themselves, but I also live I the real world, and I know it’s a big deal for some people. I would say I think I’m a better teacher because I’m out, because I’m open and honest with my students, but it is your own decision. But if you work on an ethos which makes everyone welcome – regardless of gender, sexuality, religion or race – then, when you are gay, it’s alright, because the children believe this ethos, that everyone is welcome.

Is it right to assume this also helps to combat bullying in the school?

Absolutely. It’s a very pro-active way of eradicating bullying. I wouldn’t say we’ve eradicated it completely, but it’s all about getting children to embrace and celebrate difference, so it feeds into the same thing.

Andrew Moffatt’s book No Outsiders In Our School is available now through Speechmark Publishing. You can learn more about his teaching at equalitiesprimary.com.

More stories:

Meet Eastenders’ new Johnny Carter

Another London gay sauna has closed its doors