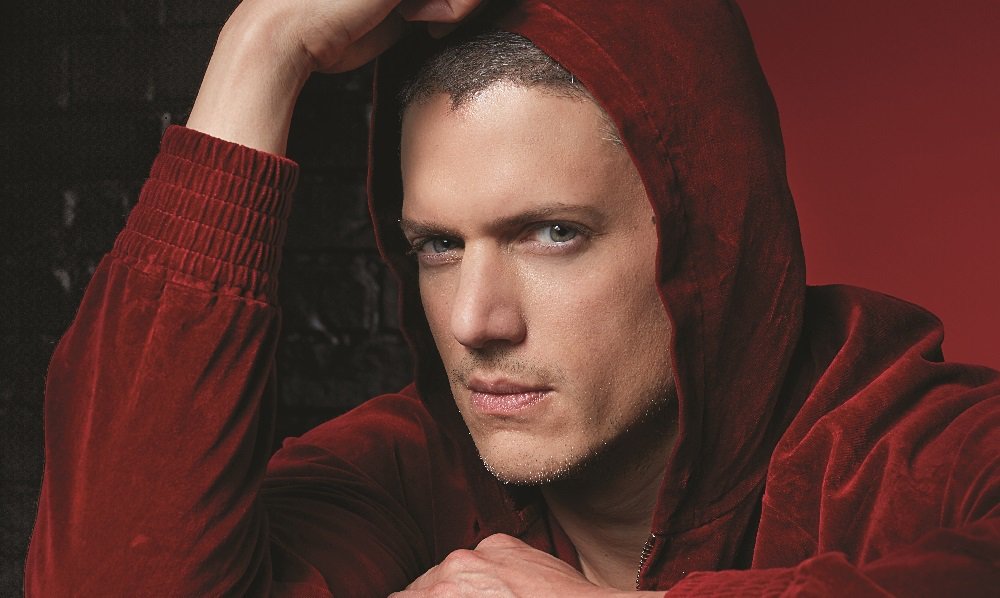

Interview | Wentworth Miller talks mental health, Hollywood and homophobia

By Josh Lee

Wentworth Miller has a message for anyone struggling to come to terms with their sexuality, anyone being bullied because of who they love, or considering suicide as a result of the consequent feelings of being lost, alone, low and in a place so dark that death looks like a viable alternative.

“I would say what others have said: it gets better. One day, you’ll find your tribe. You just have to trust that people are out there waiting to love you and celebrate you for who you are,” he says.

“In the meantime, the reality is you might have to be your own tribe. You might have to be your own best friend. That’s not something they’re going to teach you in school. So start the work of loving yourself.”

With German, Jewish, Russian and Cherokee ancestry, his parents — a black father and white mother — moved the family from the UK to America when he was 12 months old.

He continues: “Make sure you talk to yourself, in your head or out loud, like you talk to your best friend — or how you’d want your best friend to talk to you.”

Miller knows what he’s talking about. The actor and writer — catapulted to fame by his starring role in Prison Break, the sequel of which hits TV early next year — has experienced despair and depression, the agony of anxiety and soul-destroying self-loathing.

He has felt suicidal and he has attempted suicide more than once — first when he was 15. In 2013, at a Human Rights Campaign event, he talked movingly about that attempt.

Alone for the weekend at his family home, he swallowed a bottle of pills. “When someone asked me if that was a cry for help, I said no.

“I told no one. You only cry for help if you believe there’s help to cry for,” revealed Miller.

Earlier this year, after an unpleasant meme of him appeared online, Miller, 44, posted a short essay on his official Facebook page (which, he says, he manages himself as he likes to read the comments whenever he can). In an age of celebrity insincerity where publicists, managers and assistants so often mediate for and masquerade as their clients, that post comes straight from Miller’s heart. It is one of the most honest, and inspiring, statements you’re likely to read about someone’s struggle with depression, with shame, with feeling less than, with the sinking feeling that pulls you through the seats of chairs that people who endure depression know so intimately. That it comes from a famous someone makes it all the more remarkable.

“Ashamed and in pain, I considered myself damaged goods,” Miller wrote of his lowest low, in 2010. “And the voices in my head urged me down the path to self-destruction. Not for the first time.”

Born in Chipping Norton, in Oxfordshire, Miller, who appeared in The Flash, and, earlier in his career, Buffy The Vampire Slayer and Joan of Arcadia, details how he found relief from his pain in food — in the same way that addicts seek refuge from their pain with drugs or alcohol. He tells of how he managed to survive the depths of his despair and, ultimately, thrive. “Like a dandelion up through the pavement, I persist,” he says.

What strikes you when you read Miller’s missive is how heartfelt and heartbreaking it is, how he frankly details his feelings, from despair to defiance — and how he encourages other people with similar feelings to reach out and ask for help from a variety of organisations. “Someone cares,” he said, simply. And they do.

Today, Miller cares. He supports various suicide-prevention organisations, such as The Trevor Project, a hotline service aimed at gay and questioning youth aged 13 to 24.

He recently collaborated with The Mighty, the online community for people with disabilities, diseases and mental illnesses, to produce a video to try to communicate what it’s like having depression.

If you suffer from depression, you should watch it. It’s a reminder that you’re not alone. If you don’t suffer from depression, it may give you insight into the lives of those who do.

Miller, who wrote the 2013 Nicole Kidman/Mia Wasikowska movie Stoker, doesn’t need to do any of this. Not really. He could, if he was more of a Hollywood player and less of a decent human being, pay lip service to it. He could acknowledge his history but draw a line under it, for fear of becoming some sort of poster boy for crazy gays (and I include myself in that category), having cynically targeted the (surely much-coveted) gay/suicidal/mentally ill demographic.

But he doesn’t.

In the course of our interview, Miller emerges as a thoughtful, accomplished actor who thinks deeply about the roles he plays, but also as a good, kind man (who, I cannot avoid saying, is incredibly sexy). Wentworth Miller is proof that heroes needn’t come with a cape and superpowers.

But, as it happens, Miller does play a superhero, of sorts, in DC’s Legends of Tomorrow. As Leonard Snart/Captain Cold, he stars opposite Doctor Who’s Arthur Darvill, Brandon “Superman” Routh, and Prison Break co-star Dominic Purcell. With superheroes more popular than ever in pop culture, to what does Miller attribute this popularity? Are we, to paraphrase Bonnie Tyler, holding out for heroes?

“It comes down to difference,” he muses. “I think that’s what most superhero arcs are about. Someone starts out being penalised because they’re outside the norm, then they discover that the very thing that makes them different is what’s going to save the world. Apparently, comic books have a massive LGBTQ fan base. That’s probably not a coincidence.”

Today’s superheroes are more flawed than ever, more human — perhaps as invincible as ever but certainly not infallible. Marvel’s Jessica Jones is probably the best example of this. Why do you think this is?

I think more and more we’re expecting to see, or maybe even demanding to see, some reflection of ourselves on-screen. So it makes sense that our superheroes gradually become more like us. More flawed. More human. Struggling to do the right thing. Not always knowing what that is. Sometimes that’s the whole point of the story. Figuring out what right is.

How do you feel about the state of the world today? Are you more of an optimist or a pessimist?

The first. Usually. I’d like to believe — I choose to believe — that people will do the right thing. I choose to believe that if you strand two people who hate each other, for whatever reason, on an island in the middle of the ocean, and you make their survival dependent on them getting along, eventually they will. I mean, that’s Earth. The island is Earth, the ocean is space.

Away from the cameras, what was your personal coming-out journey like?

It was a long road. I did it in my own way. And my own time. When I was ready: emotionally, mentally, spiritually. When I had a support system in place. I think that’s critical. To lay a solid foundation first and then make the big life decisions.

Is looking at your coming-out through the prism of a career-choice erroneous? Was your decision more personal than professional?

Coming out — coming out publicly — had nothing to do with my professional life. I spent my twenties and thirties focused on my career, looking to make my mark. Everything else took a back seat: friends, family, community. That all came second. But then I moved into my forties and there was this reversal. Now career comes last and people come first. Speaking my truth, being in integrity, being in alignment with myself. These are the priorities now. I don’t think I’ve ever been more interested in people and less interested in Hollywood.

Regardless of your motives, many gay actors remain in the closet today in a bid to protect their careers and not alienate Middle America, although clearly this is changing, albeit not as speedily as liberals would like to imagine. Why do you think homophobia is so engrained in some people?

I think the issue might be Hollywood. I spent six years as a temp working for studio and network execs, as an assistant. I got to spend a lot of time with them. I got to see them behind the scenes. And most of them are fear-based. I don’t think the average exec decides not to hire openly gay actors because they hate gay people. Hollywood is a business. It’s corporate. It’s about profit. And if I’m an exec and I’m trying to please my corporate masters, and guarantee a big opening weekend — and you only get one shot at the box office — and I want to keep a roof over my head and I have to choose between hiring a straight actor for the lead in my movie and an actor who’s openly gay, I’m going to go with the straight actor because I don’t want to risk alienating various demographics. Not because I hate gay people. That’s my take. I could be wrong.

When did you last experience homophobia?

It was probably on my official Facebook page. It’s a very supportive space, but every so often there’s a “die, fag” and it’s always a surprise. But I remind myself that I’m the blank screen on which some stranger is projecting their shit. Those comments are aimed at me and seemingly about me but really those people are writing about themselves. That’s their work. Not mine.

Do you feel that you wouldn’t be the creative person you are today without having suffered from depression?

I don’t know. I’d hesitate to make depression sound romantic in any way because it’s not. It’s devastating. But it’s also given me material. It forced me to learn how to turn straw into gold. Creatively. To survive. A lot of my writing — first the screenplays and now the personal essays I’m posting — speaks to things I’ve gone through. Painful things. Putting that down on paper, that’s been healing. Sharing my writing with other people: healing. Knowing some of them are finding healing when they read something I’ve written, knowing they’re not alone, that’s also healing. Self-expression is so important, via whatever medium is available to you. Just find something that works for you and start the process of getting that thing inside you that’s causing pain, out.

Do you think that the stigma surrounding admitting to having mental health issues is connected to a fear of looking weak or being vulnerable?

Could be. I agree about the fear of being weak. Or being perceived as weak. But I don’t think of weak and vulnerable as the same thing. To me, being vulnerable is being emotionally open. Porous. I don’t mind if people think of me as vulnerable. I think being vulnerable is essential if I’m going to take an interest in something other than myself. But I’ve had people confuse that quality with weakness. Especially in this business. Then I have to bring out the sword.

How difficult, or easy, do you find it to be vulnerable?

Vulnerability takes practice, speaking for myself. Because the world can be a scary place. Scary for the queer community, for people of colour, for queer people of colour. Staying open, putting myself in someone else’s show when it takes work and consciousness and courage just to stand in my own. All of that takes practice. And intention.

You experienced toxic digital vitriol when a meme mocked your weight gain. How did you feel about it at the time and how do you feel about it now?

At the time, it was upsetting. But out of that came something positive. Several positives. First, I was able to practice self-expression and get it — the upset — out of me and down on paper. Then, when I shared it, people responded. A lot of people. That’s what I was talking about before. That self-expression can be of service to you but it can also benefit other people.

Why do you think people can be so cruel? Why is body-shaming so prevalent nowadays, in society at large and in the gay community especially?

I think some of it has to do with people believing — all people, not just the community you’re referring to — that if you want to feel better about yourself, you need to tear someone else down. I don’t think it works that way. Disempowering you isn’t going to empower me. Not for long. It might feel good for like five seconds, ripping you a new one, but then I’m back to feeling like shit. So I have to do it again. And again. And again. It’s an addiction. I’m always after the next fix. Because I haven’t addressed the core issue, which is why I feel shit in the first place.

That Miller is so magnanimous is i) very impressive, ii) slightly infuriating, in the nicest possible way, and iii) testament to what he describes, in relation to a question I ask him about how the divisions in America might be healed, as cultivating empathy.

“Exposing ourselves, repeatedly, consistently, to people who are not the same is key,” he said. “If I’m living in a small town and the only experience I have of another group — Muslim, trans, what have you — is via television and the websites I go to because they echo me back to me in a way that’s comfortable and comforting, how am I going to learn what it is to walk in their shoes?

“I’m not. I have to be willing, and motivated, to venture beyond my own backyard. I have to make that choice.”

Clearly, Miller has made that choice. And although he’d probably decline the label, such is his character, it makes him an inspiring role model, a beacon of hope that life can get better when it seems so dark.

Wentworth Miller: quite the man — who’s also really sexy.

Did I mention the sexy thing? I think I might have…

Photos: Magnus Hastings

Words: Gareth McLean

Attitude’s Awards issue is still available to download here. Meanwhile, our January issue is available to download and in shops now. Available internationally from newsstand.co.uk/attitude. More stories:X Factor winner Matt Terry addresses sexuality rumoursSingle & Fabulous? | The single man’s guide to surviving Christmas

More stories:X Factor winner Matt Terry addresses sexuality rumoursSingle & Fabulous? | The single man’s guide to surviving Christmas