Is it ever OK to out somebody? Four LGBTQ community voices offer their take

"In each case, the circumstances change everything," Tom Capon writes.

Pictures: Supplied

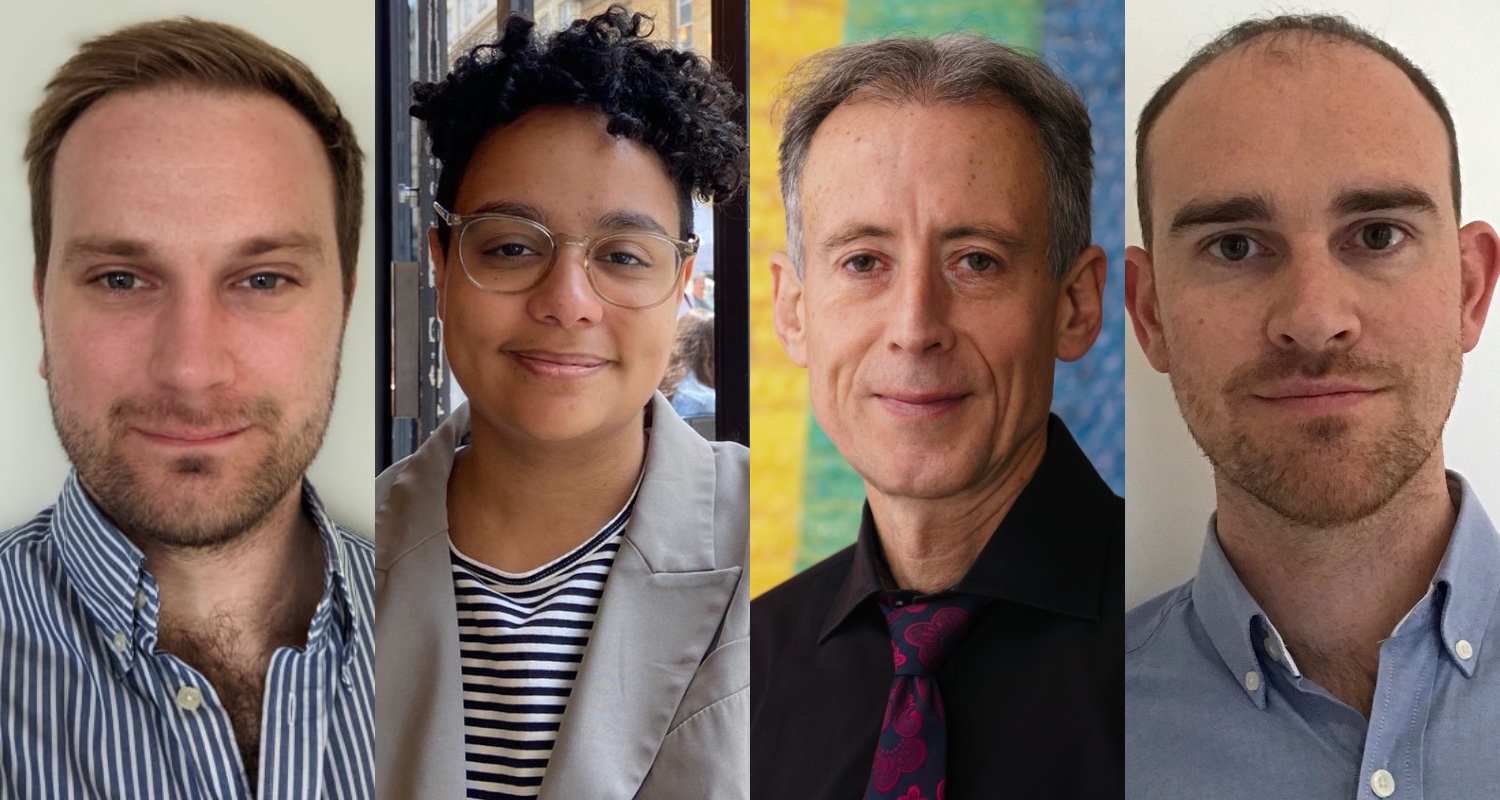

Nic Crosara (they/them) – Journalist

I vividly remember being on a crowded but quiet bus late at night with my (very drunk) friend. I’d already been out to the people in my life for a year, but as she started commenting on my transness at the top of her voice, the only thing louder on the bus was my fear.

My eyes darted around as I tried to gauge the reactions of those around us: would any of these strangers attack me before — or after — we got off?

My friend didn’t do this with malice in her heart. Her white, cis- het privilege — and intoxication — meant the thought that she could be putting me in danger didn’t even cross her mind.

A lot of these types of scenarios stem from a lack of awareness. That’s why I think it’s important to have these discussions so that those outside the community can be informed on the impact outing someone — intentionally or not — could have.

With Rebel Wilson’s coming-out story recently going viral, I hope we can all learn that someone else’s identity isn’t our story to tell.

We need to assert that everyone should be able to share their truth with whoever, whenever they want — even if that means not at all.

Peter Tatchell (he/him) – Human rights activist

Outing closeted public figures who abuse their power to harm LGBT+ people is a form of queer self-defence against homophobes and hypocrites.

In my view, people who publicly advocate homophobia while privately practising homosexuality deserve to be exposed.

Most of us would agree that someone who is assaulted in the street is entitled to fight back. The outing of queer homophobes is a similar response. We’re protecting our community from those who attack us.

Closeted homophobes have a choice. If they don’t want to be outed, all they have to do is to stop supporting homophobia. If they choose to carry on, they have put themselves in the firing line and have only themselves to blame if their secret is revealed.

The aim of outing is to embarrass and discredit the hypocritical perpetrators of anti-LGBT+ intolerance. It works by helping to destroy their power, influence and credibility, stopping them from causing further harm.

This makes it the morally right thing to do. The real extremism is not outing, but the homophobia and hypocrisy that makes it necessary.

Tom Capon (he/him) – Showbiz editor at My London

One of the first lessons you learn as a little gay boy is that it’s wrong to out people. For nearly every situation, that is true.

But what if it’s a politician enacting homophobic policies that have deadly effects on queers? Or a celebrity who is profiting from their biblically straight life?

I don’t believe you can take a hard-line moralistic view on this issue when the relative position is key. Rebel Wilson’s outing is incomparable to homophobic Hungarian politician József Szájer, who was exposed for attending a 2020 gay sex party.

Wilson’s sexuality is only your business if you make it so, while Szájer made life worse for millions. By exposing him, it not only took him off the board, but undermined the legitimacy of his movement.

Although you can argue that George Michael shouldn’t have taken an undercover cop up on his sexual advances in 1998 as it was a public place, his arrest was cruel.

His actual coming out could have, powerfully, been on his terms. (Though, at least we got ‘Outside’.) In each case, the circumstances change everything.

Jon Holmes (he/him) – Network Lead, sportsmedialgbt.com

Last summer, US website Outsports published a list of athletes representing ‘Team LGBTQ’ at the Tokyo Olympics. USA rugby sevens player Nicole Heavirland looked for her name — even though she wasn’t out.

“When I saw it wasn’t there, I was like, ‘Dang it.’ But that would have been the easier route,” Heavirland told Outsports later, finally ready to share her truth.

I can see how the prospect of being ‘pushed out of the nest’ might appeal to someone wanting to spread their wings without making a flap about it. However, there’s almost always collateral damage, with friends, family and fans unprepared for such announcements.

Outsports and outlets like mine, Sports Media LGBT+, are acutely sensitive to the impact on athletes. Meanwhile, tabloids continue whipping up gossip about mystery gay and bi Premier League footballers.

That turns coming out into clickbait, contributing towards keeping players in the closet. It’s never fair game — our stories must be ours to share, and ours alone.

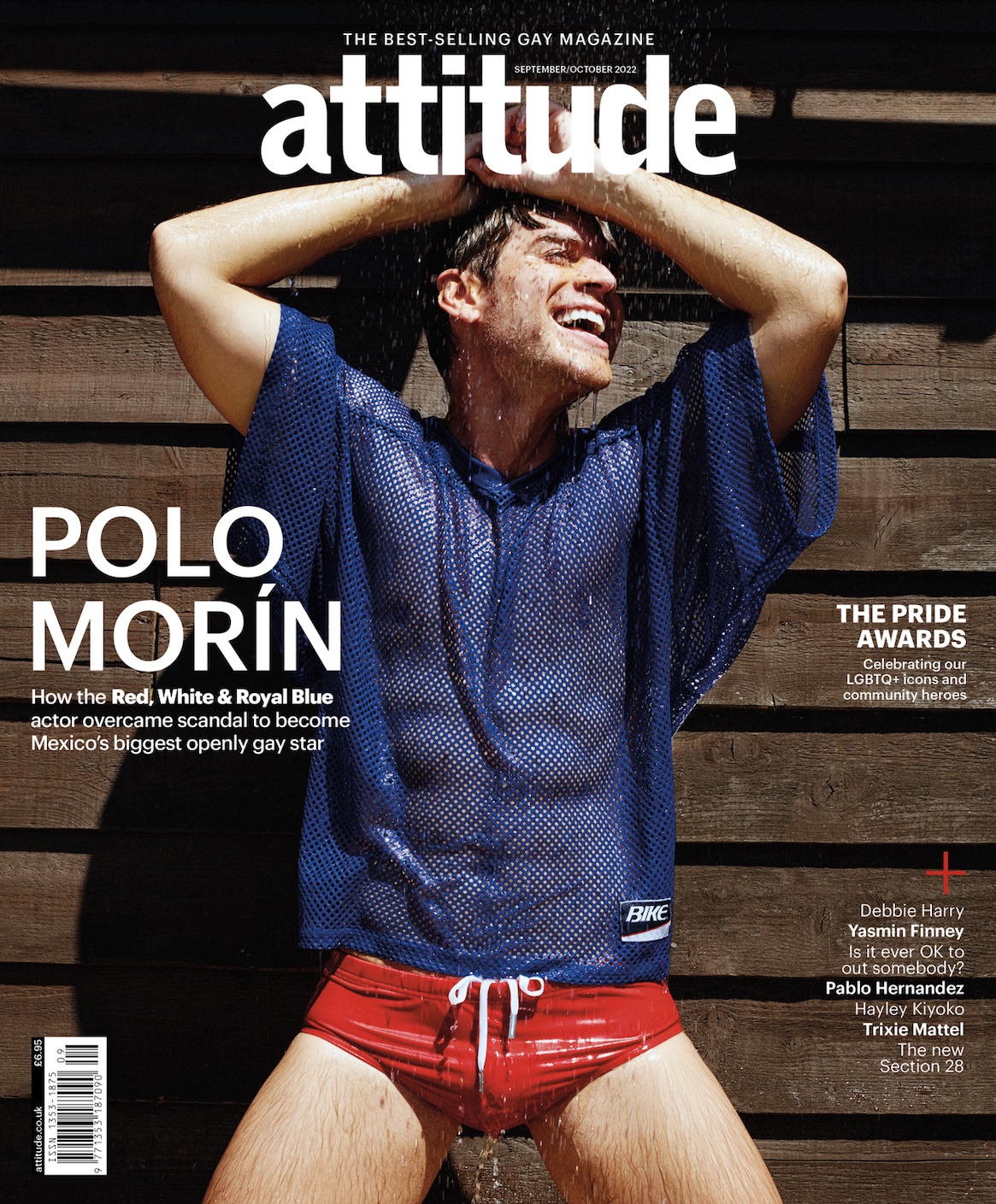

The Attitude September/October issue is out now