Justin Trudeau’s special adviser on LGBT issues reveals how Canada is listening to its queer community

By Will Stroude

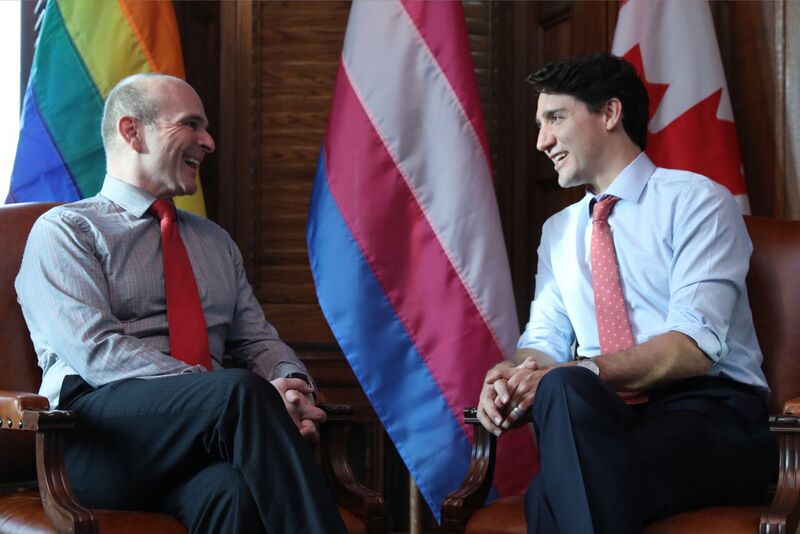

Oxford University educated Randy Boissonnault made history when Prime Minister Trudeau appointed him as special adviser on LGBTQ2 Issues in November 2016. A Member of Parliament for the Edmonton Centre, Alberta he is a crucial conduit of information connecting the LGBT+ communities across the vast territories of Canada.

“Based on what happened in the election in 2015, Canadians are interested in change,” he told Attitude during a recent visit to the UK. “And what we’re hearing from Canadians is that they value the conversation we’re having about diversity right now. And so pluralism and coming together, and that sense of diversity, is a hallmark of our government, and we’re gonna continue to communicate that very strongly.”

As Canada celebrates its 150th anniversary of Confederation on 1st July, Mr Boissonnault speaks exclusively to Attitude about the country’s progressive attitude to LGBTQ2 legislation, what progress has been made so far, and what work there is still to be done.

Your role was created specifically in this parliament.

It’s never existed before. So, two things we’ve never had: a special adviser for anything to the Prime Minister, and there’s never been a focus on LBGTQ2. The 2 stands for ‘Two Spirited’: These are people in the indigenous communities who, for millennia, had two ‘spirits’. And it is interesting because they were highly valued by the community. It was like they were touched by the creator, and so the warriors would actually go and literally be blessed or talk to the two spirited person before they’d go out to hunt. And women would do that before they started their families. It’s important for us to shine a light on that part of the community. One of the important pieces for our government is reconciling with indigenous peoples. It’s a key focus of our Prime Minister.

What does the role entail?

We can break the role down into roughly its four constituent parts: One is to be a focal point for the community into government, and then a way for the government to communicate to the community. The second piece is to coordinate the machinery of the government, to get things done. The third is to shine a spotlight on really important issues. And fourth is to continue to talk about LGBTQ2 issues within Canada, and then also externally. My job is to listen to members of community, and not just representers of organisations. If I wanna talk to members of the trans community, I need to go and find people who have an experience of what it’s like to be 15 or 16 and transitioning, or someone who transitioned in 1977, and what’s their life like now that they’re in their mid ’70s. If I’m really gonna understand intersectionality, then I want to talk to queer people of colour, and two spirited people, and I’ll go on reserve to meet with two spirited people because people find their voice in the place they’re most comfortable. And if that means we have to go to where they are, then we do that.

How does that manifest when reporting back to the prime minister?

What I say to communities is, ‘Make sure you’re not waiting for some big ‘ah ha’ day where we’re gonna have a whole bunch of things’. There’s gonna be incremental change, and when we have announcements to make on a policy that we’ve changed, then we’re gonna announce it. For example, our government is now put an end on asking for sex information and gender, you don’t have to give your gender information anymore to the social, employment and social development ministry, because we’re going through a review to say when do we need the information on gender, what are we using it for, when should it be opt in, and when do we absolutely need it, and for what purposes? That’s a whole lot of government review, which we announced only late January, so there’s an example. I meet with the team, the PM’s office and the Privy Council’s office every week.

Are there specific goals that you have? Or is it more absorbing information and identifying concerns?

It’s observing information and seeing concerns. As you know, things get done in civil society by the strength of networks. And so, I’m trying to assess that: the health of the formal networks and the health of the informal networks.

Formal networks can be charities, organisations, like Pride?

For example, we have the pride festivals in a lot of cities in Canada. We also have the Pride Centre, the community centres that serve the actual needs of people on the ground. The other piece is to have the community tell us what’s really important. Legislation is important, support is important, networks are important, we’re hearing that funding is important, but so is the fact that the government is connected to the community now, and listening. We passed legislation that will include gender identity and gender expression in the criminal code, and in the Canadian Human Rights Act, that has passed the House of Commons and now it’s with the senate. We’re also repealing an old vestige of the anti-sodomy laws on our books that affected minors, particularly gay youth. And people had been charged under that provision up until 2015. There is incremental change, and there is important change. One of the pieces that’s important to the community [is] the Just Society Report from Egale Canada: From 1969 until 1991 the federal government fired LGBTQ2 members of the government simply for being different. I am tasked with looking at an apology to the community. There’s lots to learn from what the UK government has done, and just recently with the Turing Law. How do we approach the concept of pardons and expungements?

In terms of the size of the country, is there a big difference between LGBT in the city and the rural areas in terms of acceptance?

It’s an issue that’s been raised with me across the country. I grew up in a small town, I moved to the city in my area, in Alberta, and there is work to do across the country. I’ll put it to you this way, in my election in Edmonton Centre, as an openly gay candidate, my sexuality didn’t come up. During the nominations, somebody’d said, “Oh, are you the gay candidate?” I said, “No, I’m the candidate who happens to be gay.” And they’re like oh cool. And it’s funny, until I was on the equivalent of you know, Attitude Magazine for my city, and I had the big word, you know, ‘gay’ on the front of the cover, people would say, “I didn’t know you were gay.” So, it depends where you are. And there are people in our country who feel isolated, who live in rural Canada. And part of it is helping everybody to understand that we’re stronger because of our differences, not in spite of them, and that includes sexual orientation.

Has there been much negative reaction to the pro-LGBT agenda that Justin Trudeau has been pushing?

No. I’ve not seen or heard of any.

Would you say Canada as a whole tends to be a more open-minded society?

We value diversity and we value all kinds of diversity, and it’s one of our strengths. If you take a look at how far we’ve come since 1969, when then justice minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau decriminalized homosexuality and had a famous quote that, “the state has no business in the bedrooms of the nation.” It’s taken a long time to get to this point. I mean I never thought as a young person that I’d be going into politics. When I knew who I was, when I knew I was gay, I’m like there’s no way I’ll ever be in politics. Like when I was at Oxford in the UK, I was closeted in 1994. I didn’t come out till 28. Societies evolve.

Organisations around the world are still slow to take up any kind of recognition of LGBT history.

One of the things that we’re finding through this new role in Canada, is how invisible the community at large is in the data. And that, if that’s the case, in a G8 country like Canada, then what’s it like around the world? And the World Bank now has a head of diversity globally, and I tell you that LGBTQ people around the world are invisible in the data. The World Bank is now leading a charge to work with individual countries to make sure that we are more visible in the data.

Does the Canadian education system include LGBT history as part of its syllabus?

This is one of the differences between our two countries: [In Canada] the administration of healthcare and the education systems are run by the provincial governments. So the answer to your question is it depends where you live. The curriculum in Ontario and Quebec would be likely ahead of the pack. There’s a new democratic government in Alberta now, after 43 years of the conservative government, so there’s changes coming. In many parts the country is still getting to the point where it’s integrating indigenous history into curriculum, so this honestly is gonna take some time.

I understand there’s still distinctions between what’s allowed and what’s not allowed regarding conversion therapy in Canada?

That again is run by the provinces, so that’s where the disparity exists across the country. This is why the expressions gender identity and gender expression are so important. Because no one should be required to have gender affirming surgery for them to feel confident to express their gender. Not every jurisdiction in the country is there yet, and it’s up to each provincial Ministry of Health to determine how much of gender affirming surgery is or is not covered. We don’t have any legislative authority in the provincial jurisdiction, but we can demonstrate moral leadership. And the federal government does fund, in part, the health system. There are transfers that go from the federal government to the provincial government, so that’s an important piece where we can indicate strongly what we’d like to see happen on the ground.

What are your feelings around Trump’s comments in regards to transgender rights?

What I can say is that, I can tell you what we’re doing in Canada is that we’re working very hard to see that the trans community is heard and integrated into our work. We continue to talk both internationally and domestically about our approach to diversity and how we’re supporting the LGBTQ2 and that’s important for us, it’s part of the reason we’re here. It’s that community of nations that are sharing experience. I can tell you that I have met with the deputy secretary general of the Commonwealth. I’ve spoken to the organization of American States. The PM has spoken very clearly at La Francophonie in Madagascar last year, where he said very clearly in a room of leaders, for whom this is not something that they think about on a daily basis, that we have to do more for the LGBTQ2 community. And so our relationship with the United States is a strong one, we continue to work on a daily basis with our largest trading partner and these are conversations that we have.

In term of the Commonwealth how are you promoting ideas of change especially with countries that oppress people.

The PM’s been very clear that Canada is re-engaging in the Commonwealth and you see that from our three ministers connected to this embassy: international trade, international development and foreign affairs. What’s important is the fact that we treat each of these relationships as individual and complex relationships. They are trade, human rights, cultural exchanges and it’s important to work with each country on its own path of development, and that over time, you know, the long arc of history bends towards justice and progress, and how can we help to make sure that we’re supporting countries where it’s important.