Meeting the HIV-positive gay men who outlived a death sentence

By Will Stroude

Being diagnosed with HIV in the ’80s and ’90s left most gay men – usually correctly – thinking they had little time left to live. Incredibly, some beat the odds and live healthy, fulfilling lives today. But many of them carry the scars of the past and a strong sense of guilt simply for surviving when so many of their friends and lovers did not.

The 67th Academy Awards in 1995 will always be remembered as the night Robert Zemeckis’ saccharine dramedy Forrest Gump confirmed its standing as one of the greats of modern cinema, turning 13 nominations into six wins, including for the coveted best picture, best director and best actor.

It became such an integral part of the cinematic zeitgeist that it was eventually selected for preservation in the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry, in part for its engagement with the more contentious aspects of America’s turbulent past.

But while Tom Hanks’ protagonist literally stumbles through iconic scenes and historic scandals, such as the war in Vietnam and Watergate, even influencing their outcome, his experience of the era’s defining health crisis — the HIV epidemic — is far subtler, with just the implication that the condition which causes his wife’s death is, in fact, HIV/Aids.

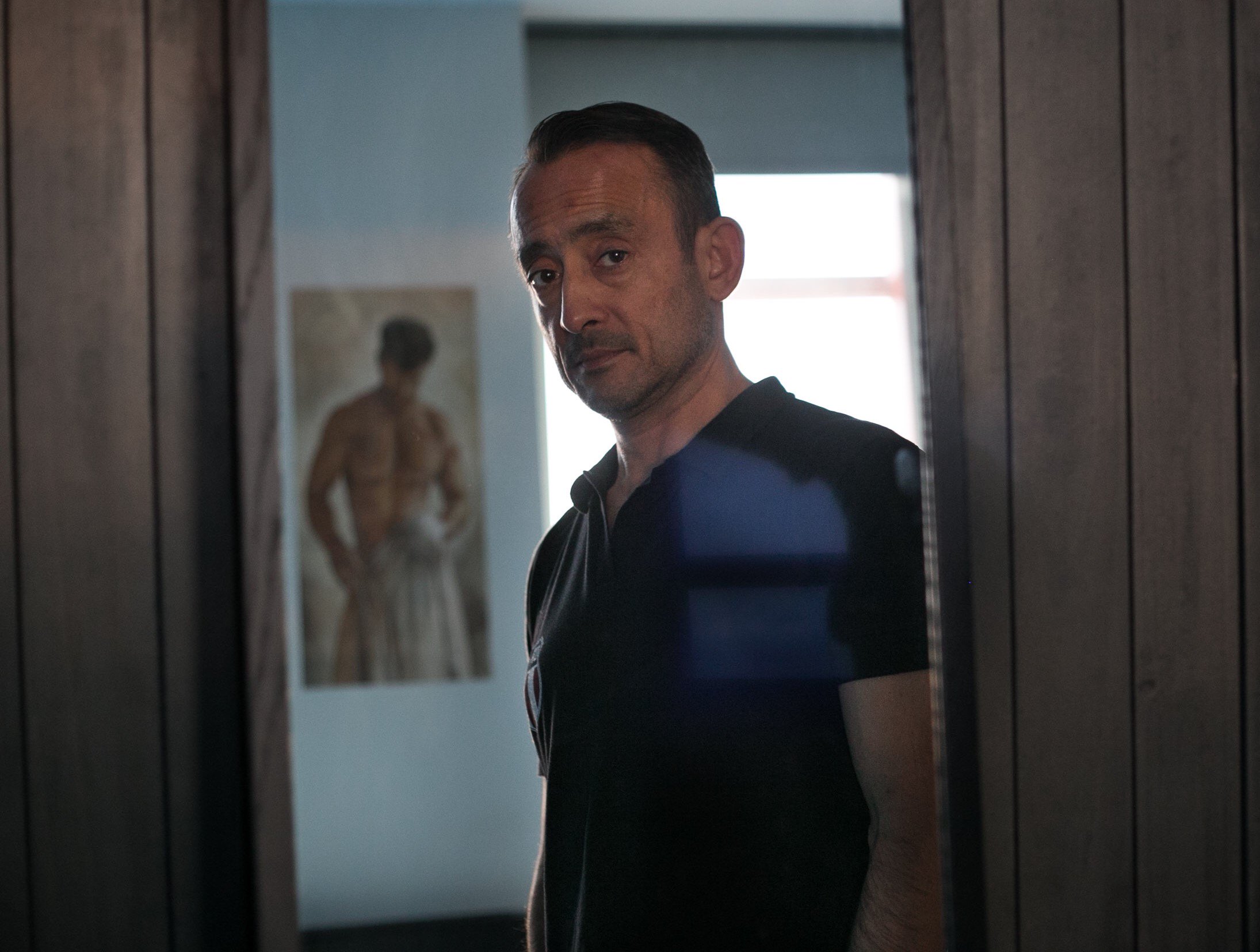

Tim, 51, will always remember the 1995 Oscars as the night his own partner, Carlos, died of an Aids-related illness. They’d met six years before — both at the age of 25 — in a New York gym after Tim had moved to the city from Santa Fe, New Mexico.

As the Academy Awards played out on the TV in the background of their New York apartment, friends and relatives dropped in to say goodbye until Carlos’ eventual passing late that night.

The memory of caring for a dying partner will be a familiar experience for far too many gay men who lived through the Eighties and Nineties. At the epidemic’s peak, Tim and Carlos had already lived through the Aids-related deaths of close friends. Tim would go on to lose a cousin and another close friend.

In the aftermath of Carlos’ death, Tim, then 30, managed to stave off his grief long enough to get himself to a New York City clinic called Project Inform, which carried out tests for HIV. He tested positive.

At that time, with no antiretrovirals available to control the virus, such a diagnosis was nothing short of life changing. Having seen so many before him die, he understood the sheer weight of the news.

Tim received no assurances when he went for follow-up medical tests a few months later and was told he had a dangerously low T-Cell count of just 78 (the white blood cells which detect and fight infections), coupled with a high viral load, in the millions (the amount of HIV genetic material in the blood). For Tim this was tantamount to a death sentence.

“My doctor said: ‘we don’t have much time left,’ so I didn’t think I was going to be surviving much longer,” Tim says. He assumed he had just a few years to live — if that. Considering everything he knew about the condition from the media, doctors, rumours and his own experiences, it was a fair estimation.

Shortly after his diagnosis, Tim resigned from his job as an investment banker and used his savings to travel to Europe. After trips exploring the likes of Paris and Amsterdam, both with a friend who was also HIV+, he wound up in London in 2003 and has lived there ever since.

It wasn’t until he turned 40, a few years later, that he began to realise he would probably be OK, that he would survive and that planning (or saving) for the future would not be a waste.

As clichéd as it sounds, for the best part of a decade he’d been living in the moment, always assuming he wouldn’t be around two, three, or maybe four months later. “I never thought I would be living in London, thinking: I’m still healthy I’m still alive,” Tim says. “Even my mindset coming to London in 2003 was like: ‘how much time do I have left’. When I moved here I tried to do as much as I could to travel and see lots of different places because I just didn’t think I had much time left to live.”

He’s grateful to have survived far longer than he ever thought possible but his travels and insecure living and employment situations have proven costly.

“When you’re in your thirties and forties, you’re not really financially preparing yourself to retire; you’re living in the moment, you’re not living for 20 years from now,” he explains. Now working as a contract financial consultant in the City, he also spends time attending the Terrence Higgins Trust’s (THT) health, wealth and happiness events for the older generation living with HIV. It’s one of the few groups available to a much-ignored community.

“You’re not really thinking about saving, pensions or retirement funds like other people. Most of us who are HIV positive for a long time are not really financially secure.”

Tim’s right — his situation is not unusual. In the UK, at least we are now able to minimise the physical impact of HIV. But the mental scarring and social impact long-term survivors were exposed to will take far longer to abate. Many are still recovering from the trauma of the epidemic: the stigma they were exposed to, the weight of short-term living, the lack of security, the impact on friends and families. And, of course, survivor’s guilt.

Canadian Angus Pelltier, 53, was given five years to live when he was diagnosed. That was in 1985. At that time, he had no idea what HIV was or how it was contracted.

What he did know didn’t inspire confidence: it was referred to as The Gay Cancer, there was no medication beyond the initial trials for the only-partially-successful AZT, his best friend would rather abandon him than help him through it, and three gay men he knew had killed themselves after discovering that they too were positive.

Like Tim, the diagnosis changed Angus’ perspective and ambitions for what little time he thought he had left. Furthering his education, getting a great job, buying a house or settling down were now insignificant trivialities that were out of his reach; petty ambitions to be discarded.

“You were given a death sentence and no one knew what was going on,” says Angus, who was living in Toronto at the time and had planned to become a nurse. “I changed completely; I didn’t really have the drive any more. I decided at that point that I was gonna travel to Europe. Instead of feeling sorry for myself, I decided that I was going to live everyday as if it was my last.”

He received his diagnosis on 28 August and by 1 September he’d handed in his notice at work. As the New Year came around, he found himself in Europe. After falling in love with London, he moved there permanently in the winter of 1989. Although he’s lived in Clapham ever since, it was only when he turned 50 that he afforded himself the luxury of planning for his future.

“I have certainly had my demons to deal with, but on the whole I am all right,” says Angus, who now runs a successful dog-minding business.

“I only went on meds at 50 and my viral load is only at 100,000. I know people who’ve been in the millions when they go on their meds. I was one of those rare beasts. That was when I was like: ‘you can get a mortgage and you can move forward’. That was when I grew up.”

Neither Tim nor Angus can say for certain that their paths would have led to London had they not been diagnosed with HIV. What they can say is that as long-term survivors, they still feel the effects today, if not physically then financially, mentally and — especially — socially.

Glen grew up in northern Minnesota and felt the social impact of his diagnosis the moment he opened up to his family about it. Although he was diagnosed 23 years ago, a decade would pass before he told his parents. When he did, they were very supportive, but his siblings (he is the youngest of nine) wanted nothing to do with him — and he hasn’t spoken to many of them since. In addition, his niece uninvited him to her wedding.

After a period in which his partner and mum passed away in quick succession, he too felt compelled to move to London. “I realised that I had no ties to America,” says Glen, 54. “But I didn’t have any money saved up. Then I remembered that I’d purchased life insurance back in 1985.

“I was certain I would be dead in a few years, so I cashed in the policy, gave away all of my possessions and started off on a new adventure. That’s what a lot of us did. We thought, ‘well I’m not gonna live till I’m 70 so I might as well explore the world’.”

Glen gave himself five years to live. With $40,000 to his name, he paid off his debts and moved to London with the intention of dying there.

With no savings and only working freelance as an artist and graphic designer, Glen’s situation is far from secure. Living in a rented apartment in Tooting Bec, South London, he is finding himself being drawn back to the country of his birth.

“I have been feeling an inner tug, pulling me to go to America for a while,” he says.

“I do have a potential job as a live-in carer for an elderly woman in California, plus I haven’t seen my family in more than 10 years. But London will remain my home and I plan to return.”

The HIV epidemic had already changed the course of 63-year-old retiree Chris’ life long before he learnt of his own status. In 1998 his partner of eight years, Steven, became very ill and was hospitalised in London.

“I went along and a mutual friend was there. When we were leaving, I said: ‘well it doesn’t look very good, Steven’s not going to survive is he?’.” “He’d been living with it right up to the time it turned into Aids which is why he was hospitalised. By that time, it had actually got into his brain, which started to affect his vision, his personality and he was given a few months to live. At Easter he was told he wouldn’t survive beyond September.” Steven lived until January the following year. Chris looked after him as he went in and out of hospitals and hospices. He would spend every other weeknight and entire weekends with him, then return to work at Hackney Council.

Eventually the severity of Steven’s condition made leaving home an impossibility, and nurses had to visit him until the day he died. A year after Steven’s death, Chris was diagnosed as HIV+. “I became slightly ill,” he says, reflecting on the period in January 1999. “The doctors said it was stress and asked if I wanted time off work, even though I’d told him all the circumstances.

“I developed a really bad cough. Over the course of about six months that became pneumonia and I ended up in hospital, shortly after being diagnosed with HIV.

“At that stage I didn’t really have any plans,” he continues. “I’d lost my partner, I was still working and, after going into hospital, I was finding that difficult so I went part-time. I was working in local government so my boss was understanding and I was able to explain the full situation to him. I got a lot of support from the people I worked with, which wouldn’t always be the case.”

Now 63, retired on medical grounds and living in North London, Chris struggled with his diagnosis and was, until recently, receiving counselling through THT. Living through decades of stigma, health complications and losing loved ones took its toll.

It’s this — the overwhelming loss of life experienced by the gay community — that perhaps cuts the deepest wound in the psyche of those who survived. For those diagnosed during the epidemic, surviving long after the many friends, partners, flings and acquaintances have died, represents an inescapable burden.

It’s been 21 years since that night in a New York apartment, where Tim watched Carlos die as Tom Hanks stumbled through a mawkish acceptance speech in the background. It’s been 21 years since Tim himself found out he was living with HIV. Despite everything that has happened in the two decades since, Tim thinks about that night — and those he’s lost — every day.

“My partner was HIV positive and passed away quickly, but I’m still here — in my fifties, carrying the torch for them, living for them.”

For details on THT’s Health, Wealth and Happiness project, email healthwealthandhappiness@tht.org.uk or call 07467 913956.

To order a free self-sampling HIV kit go to www.test.hiv, and to find your nearest sexual health clinic visit nhs.uk.

For more information about World AIDS Day visit worldaidsday.org.

This feature first appeared in Attitude issue 277 – in shops and available to download now.More stories:‘World AIDS Day is about remembering those who’ve fallen – this is our war’

Northern Ireland politician ‘didn’t know that heterosexual people could contract HIV’