Victorian gay men and the lure of Rome

By Ross Semple

Say what you like about the hipster beard, it has made the Victorians seem a lot less distant. Now that half of Shoreditch looks like them, those long-dead men in sepia photographs seem real enough to smell.

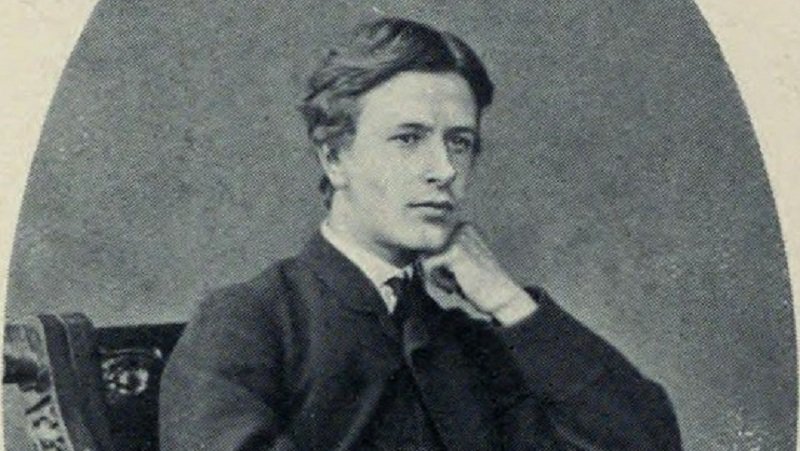

I have been trying to get inside the head of the male Victorian as research for my novel The Hopkins Conundrum, which is based on the life of the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. His writing is notoriously hard to understand, but his pent-up passions are easy to identify in the frenzied repetitions and climaxes of his verse. Think a poetic version of Van Gogh.

The son of an insurance broker, Hopkins was born in the London village of Stratford in 1844 and then moved to Hampstead. He was a small, pale boy who was rubbish at sport. We know from his diaries that he mooned over handsome classmates or grimy coal-merchants’ boys that he saw in the street.

By the time he reached Oxford, he was obsessed with writing verse. The invention of the gramophone was still decades away so poetry was the standard means of cultural expression, and young people wrote it as well as read it. There was nothing unmanly about this – Hopkins’ strapping friend Robert Bridges, a leading university oarsman, ended up as poet laureate.

What really defined young people culturally – and was often a big clue to their sexuality – was their attitude to religion. Being drawn to the Roman Catholic church in the 1860s was like listening to Jimmy Somerville, Boy George or Frankie Goes to Hollywood in the 1980s.

At the time, Oxford was the centre of a movement to revive ‘high’ Anglicanism – to make the Church of England more Catholic. Arguments over the use of incense, what kind of robes a priest could wear and whether or not he should kneel before the altar were burning issues. Everyone had a view on ‘ritualism’, as these dangerously foreign tendencies were known, and your stance spoke volumes about who you were. The issue was the Brexit of its day.

For young men like Hopkins, who had few other ways to express their sexual difference, flirting with ‘bells and smells’ was their equivalent of wearing eye-liner or cross-dressing. The news every parent really dreaded was that their son had “gone over to Rome”. In Hopkins’ case, it was worse: he became a priest, and not just a Catholic one, but a Jesuit – an order viewed as a dangerous cult by his family and friends.

Other young gay men found even more ostentatious forms of expression. The boy poet Digby Dolben, who appears in my novel because Hopkins was hopelessly in love with him, was expelled from Eton for going about the countryside dressed as a barefoot medieval monk. His piety did not stop him having a passionate physical affair with his best friend.

And in the highest ranks of the Church, the Catholic convert Cardinal Newman lived openly – albeit chastely – with the man he loved, asking to be buried with him.

None of this was lost on Rome’s opponents. The novelist Charles Kingsley, who helped popularise the idea of “muscular Christianity” as the better alternative, attacked the Anglo-Catholics for their “die-away effeminacy”.

I wanted to explore this history in my novel because it seems remarkable nowadays, given the extreme homophobia of the Catholic Church under the last two popes and its current British cardinals.

To me it’s not just a fascinating cultural phenomenon. It is also cause for optimism, because it suggests there is nothing intrinsically homophobic about the Church itself.

If it changed once, it can change again.

The Hopkins Conundrum by Simon Edge is published by Lightning Books on 18 May, price £8.99.

Words by Simon Edge